Links Between East and West 30 The Glorious Ages 东西方的连接30 - 辉煌时代

Introduction

The fundamental concept of “freedom” has been one that permeates history. Today, people regard freedom as an inalienable right not only because renowned philosophers and politicians have stressed its significance of it. One values freedom as it is the primary force that drives social progress. This essay will assume that by the word “freedom”, one generally refers to two kinds of freedom: physical and spiritual. The former kind encompasses the freedom to travel, the freedom to work, and the freedom to act in the physical world without hindrance; the latter kind includes the freedom of speech, the freedom of religion, or the freedom of thought and expression. Modern societies often place more weight on spiritual freedom, but physical freedom is the foundation for spiritual freedom. This essay will examine the importance of physical and spiritual freedom through case studies of ancient China, India, and Europe during the Enlightenment.

Example 1: Spring and Autumn Period of China

In ancient China, the Spring and Autumn period witnessed the flourishing of philosophy and theories on politics. This time of continuous warfare and chaos from 770 to 476 BCE did not allow a single political force or regime to control large swathes of China. There were long periods of uncertainty and back-and-forth between different powers. Such chaotic times proved to be indirectly beneficial for pioneering thinkers and social experimenters to gain influence. This period witnessed such an unprecedented burst of pioneering philosophy that Chinese historians have labeled it the era of “A Hundred Schools of Thought”.

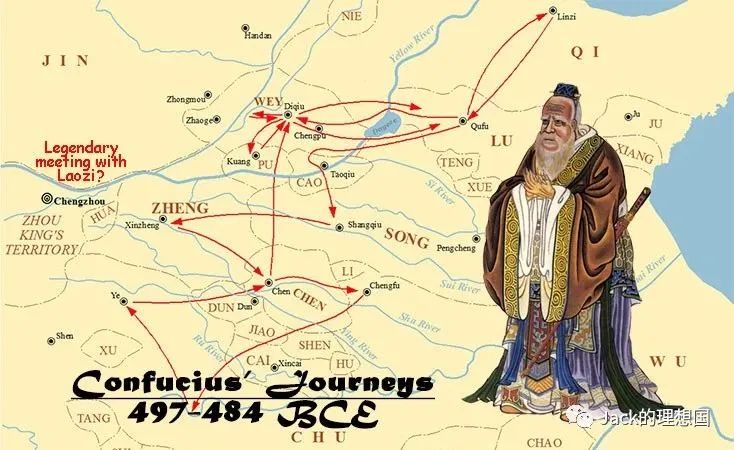

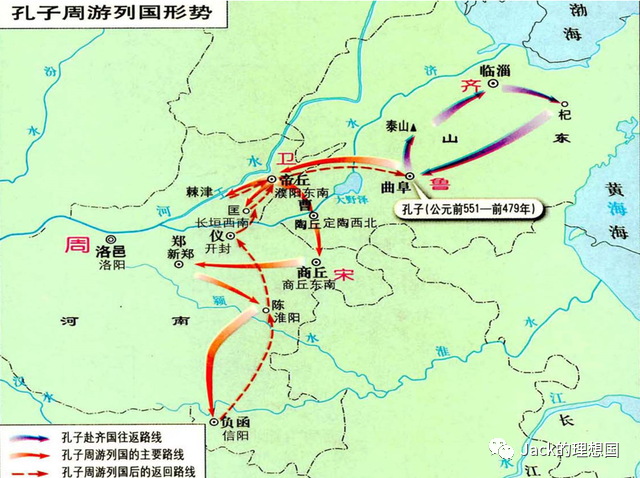

(Map of Confucius' travels)

While certain risks were magnified, philosophers and theorists during the Spring and Autumn Period possessed physical freedom. That is, they could travel across China without physical exposure to risks of captivity or large-scale political persecution. For example, Confucius famously visited most major states from around 497 BCE to 483 BCE. Throughout these 14 years of extensive travelling, Confucius, known for his poignant comments on politics, did not experience major restraints on his physical freedom. Various states captured him several times, but these captures were usually short and did not negatively impact his political career. China then granted such physical freedom precisely because there was no political or military hegemon. No state could exert total control over vast regions or the paths of scholars like Confucius.

Physical freedom was indispensable for the “A Hundred Schools of Thought” to emerge. First, one can only find inspiration if they are physically allowed and can move around. Retake the example of Confucius. During his extensive travels across China, he sought inspiration from many contemporary thinkers and masters in various fields, such as Lao Tzu, arguably the most important philosopher in the Taoist School. His meeting with Lao Tzu partially explains the similarities between the Confucian and Taoist schools. Confucius took some of the ideas from Taoism and adjusted his thoughts accordingly. For instance, Confucius argued that people’s natural “morality” should be the basis for any form of rule. This emphasis on “morality” can be traced to an argument by Lao Tzu that every pattern or creation in this world resulted from some natural order and that people should follow this natural order when making decisions. From this example, one can see that Confucius could make his school and system of thought as significant as it has been acknowledged, thanks to his physical freedom to visit different areas and different groups of individuals.

Second, physical freedom was imperative since it gave the thinkers platforms to disseminate their thoughts. Confucius could travel extensively and spread Confucianism thanks to his physical freedom. As The Analects, a book that systematically collected the teachings of Confucius, recorded, Confucius taught innumerable amounts of students located in many different states.

The Chinese philosophers from the Spring and Autumn Period also possessed spiritual freedom. That is, they were free to formulate unique opinions and express them in any suitable way. No central authority was powerful enough to dictate thoughts across vast areas. The term “A Hundred Schools of Thought” is a testimony to the level of spiritual freedom that the Chinese thinkers experienced. For instance, one school was the “Legalist School”. This school believed that the most effective way to rule would be through stringent law codes and serious punishments. However, another mainstream school of thought was the “Taoist School”. People who championed the Taoist School argued that it would be best to follow the patterns in nature and reject too much artificial design. These two schools opposed each other directly, but they coexisted during roughly the same period. Their coexistence was due to the general lack of centralized authority that could clamp down on the freedom of expression.

Spiritual freedom was vital for the Chinese philosophers. One can view spiritual freedom as the cornerstone for pioneering ideas. With restrictions on speech or thought, it would be difficult to imagine Confucius coming up with his groundbreaking comments on human nature and political structure, as he would be fearful of expressing politically wrong opinions. Further, an idea can only be pioneering if it can bring some form of impact to a broader audience or society. Spiritual freedom gives ideas the wings to fly a unique path, which would prevent these ideas from blindly conforming to social orders. Authoritarian states have restricted spiritual freedom, which pinned ideas to dogmatic social structures, making it difficult to generate social vitality or an innovative spirit. Most major schools from the “A Hundred Schools of Thought” could deliver transcending remarks that completely reimagined the social order thanks to purer spiritual freedom.

Example 2: Siddhartha Gautama and Buddhism

Another noteworthy culture during the Axial Age was ancient India. One of the periods that witnessed the burst of inventive philosophy occurred around the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. The leading figure of Indian philosophy during this time was a prince called Siddhartha Gautama, more commonly known as Buddha. He was regarded as the founder of Buddhism, which seeks spiritual freedom.

Born a prince that lived luxuriously in a palace, Siddhartha Gautama did not possess much physical freedom at first. He was not allowed to leave the palace until he was 29. Although he enjoyed a well-protected lifestyle, the lack of physical freedom and lavish lifestyle took a toll on his mental state. As the years passed, Siddhartha felt barren spiritually. He could not see the complex nature of his surroundings, so he had no inspiration to fill in the blanks in his mind.

Fortunately, at the age of 30, Siddhartha eventually gained physical freedom. According to tradition, one night, he left the palace on his own to go for a walk. What called him to leave his palace could be his heart that yearned for freedom and desired to observe the reality. From that point onwards, Siddhartha never returned to his palace, having spent the rest of his life travelling around Nepal, India, and Sri Lanka.

(Siddhartha and the Four Sights)

Physical freedom proved to be crucial for Siddhartha to reach enlightenment. Just like Confucius, Siddhartha utilized his physical freedom to look for inspiration. For example, his meditation focused on solving his questions about human suffering and desire. However, he came up with these questions based on four real observations of his surrounding environment. Shortly after he left the palace, he saw a man bent with old age, a person afflicted with sickness, a corpse, and a wandering ascetic. These sights prompted him to wonder why suffering occurs and how to alleviate it. Along his journey, Siddhartha met some renowned teachers of philosophy. These teachers taught him about the prevalent religions and beliefs around India and its neighboring regions. Although Siddhartha was not satisfied with his learning, his lessons with these teachers gave him a more comprehensive mind. Without physical freedom, most of this inspiration would not be found, and the road to enlightenment would be more crooked.

Unlike physical freedom, Siddhartha had an innate spiritual freedom that could not be imprisoned. His environment allowed him to freely explore, formulate, and articulate opinions or beliefs. But the true driving force behind Siddhartha’s journey to enlightenment was his irrepressible yearning to seek knowledge and his will to not easily conform to any system of thought. When his father “imprisoned” him in the palace, he was unwilling to let his spirit fall into the void. He always had this hidden curiosity and a keen eye for the real world outside the palace. Siddhartha kept his mind clean for his entire life, allowing him to enter a state of pure meditation.

Siddhartha’s spiritual freedom was what shaped his thoughts that coalesced into Buddhism. Buddhism is, in many ways, quite different from other universalizing religions. For instance, Buddhism concentrates more on human nature and the natural cycles of life. Buddhism does not deify its founder or any of its sages but teaches the history of their lives and how they came to enlightenment. In other words, Buddhism is a religion that devotes more attention to the real elements of reality. One can attribute these unique aspects to the spiritual freedom of Siddhartha, which allowed him to think out of the box and focus intrinsically on objective observations of reality, irrespective of overarching social norms.

Example 3: The Enlightenment Thinkers

As explained in the previous essay, Aristotle can be regarded as one of the greatest intellectuals in western history, who carried out pioneering work in many academic fields. He heralded a western tradition of prudent research, reasoning, and comprehensive observations of reality. Aristotle could create outstanding work in many fields due to his physical and spiritual freedom. About 2000 years later, in 17th-century Europe, there was a similar burst of new philosophy and theory. This burst is known as the Age of Enlightenment.

Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries was plagued by continuous warfare, such as the Dutch Revolt (Eighty Years War) or the notorious Thirty Years War from 1618 to 1648. These wars destabilized the situation in Europe and there were many shifts in power. For instance, the 1600s witnessed the decline of Spain and the rise of France and Great Britain. These power shifts ensured that no kingdom or empire had the clout to control vast areas of Europe and that there would be a strong diversity of culture.

Philosophers and writers at that time indirectly benefited from this chaos. Like the thinkers during the Spring and Autumn Period in China, these European scholars enjoyed physical freedom. Take the example of John Locke, one of the most influential thinkers of his era. John Locke spent most of his life in his birthplace, England. England in the 17th century was tumultuous with fights for power between the Crown and politicians who wanted to form a republic. Although Locke was an ardent participant in politics, this situation almost played to his advantage, as he could express his pioneering thoughts on government without worrying excessively about getting imprisoned physically.

The possession of physical freedom yet again permitted John Locke to seek inspiration and the ideas of contemporary thinkers. During his years as a student, Locke could travel around England to learn knowledge. For example, at Christ Church, Oxford, Locke became obsessed with the works of Rene Descartes, inspiring him to delve into experimental philosophy and the liberal arts. In 1667, Locke traveled to London to meet Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the First Earl of Shaftesbury. Anthony Ashley-Cooper left profound impacts on the political views of Locke and encouraged him to work on some of his most notable writings, including Two Treatises of Government. Without physical freedom, Locke would probably not encounter these influential figures that left such positive marks on his system of thinking.

The Enlightenment thinkers also experienced a time of relative spiritual freedom. Many places across Europe, such as France, underwent profound changes in their politics, economics, and social structures. Periods of transition exerted less rule over the freedom of thought and expression. The French thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau is a case in point. Rousseau was born in 1712 and spent a major portion of his life under the reign of Louis XVI. The French society during the time of Louis XVI was full of tension and clashes between the different social groups. Under such a tense circumstance, Rousseau found space and freedom to formulate his groundbreaking views on a democratic government and the “general will”. His novel arguments concerning the structure of a government heralded the French Revolution and a tremendous shift in European politics from monarchism to democracy.

The spiritual freedom in Rousseau and most other Enlightenment thinkers proved vital for their ideas to effect a greater impact. Only with spiritual freedom could these Enlightenment philosophers have the audacity to experiment with trailblazing concepts concerning politics and the liberal arts. For instance, Rousseau’s concepts of the “general will” and “direct democracy” could become the cornerstones of the radical French Revolution because these ideas reached far into the unknown and were wildly imaginative. As an example, in one segment of The Social Contract, Rousseau inventively argued that revolutions are in many ways inevitable, writing, “periods of violence…when revolutions do to peoples what certain crises do to individuals, when the horror of the past takes the place of forgetting, and when the State aflame with civil wars is so to speak reborn from its ashes and recovers the vigor of youth as it escapes death's embrace”. These arguments that urged many to rethink history and politics could only appear thanks to the spiritual freedom of Rousseau.

Conclusion

Overall, this essay illustrated that physical and spiritual freedom are two prerequisites for an age of philosophy. Further, through case studies of history’s most influential and brilliant thinkers and periods, it is clear that these two kinds of freedom have immense potential power. For an individual, planting the feet solidly on the ground and caring genuinely for the world are needed to keep the body and mind free. For a society, constructing a free and tolerant environment and encouraging the growth of diversity are the fuel for social development. However, it should be noted that restraint must be put on spiritual freedom in particular. When philosophers have the total freedom to express their thoughts, it can often lead to detrimental extremism. Societies have mostly achieved the macro balance through continuous experimentation and oscillations between authoritarianism and liberalism.

WORKS CITED

“Buddha | Biography, Teachings, Influence, & Facts | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2023, www.britannica.com/biography/Buddha-founder-of-Buddhism. Accessed 22 Jan. 2023.

History.com Editors. “Buddhism.” HISTORY, HISTORY, 12 Oct. 2017, www.history.com/topics/religion/buddhism. Accessed 22 Jan. 2023.

“Enlightenment Thinkers and Democratic Government.” Building Democracy for All, EdTech Books, 2020, edtechbooks.org/democracy/enlightenment. Accessed 22 Jan. 2023.

IMAGES FROM

http://bhoffert.faculty.noctrl.edu/HIST165/02.Confucianism.html

https://www.hinduwebsite.org/buzz/wisdom-of-the-Dhammapada.asp

https://wappass.baidu.com/static/captcha/tuxing.html?ak=572be823e2f50ea759a616c060d6b9f1&backurl=https%3A%2F%2Fmbd.baidu.com%2Fnewspage%2Fdata%2Flandingsuper%3Fthird%3Dbaijiahao%26baijiahao_id%3D1662871802245236013%26id%3D1662871802245236013%26wfr%3Dspider%26for%3Dpc%26c_source%3Dkunlun×tamp=1674380848&signature=cf756b8f23070d0fd7aa63cf35ffbe11

简介

"自由 "一直是贯穿历史的重要概念。今天,人们将自由视为一项不可剥夺的权利,不仅仅是因为著名的哲学家和政治家强调了其重要性。人们重视自由,因为自由赋予了人类社会发展的根本动力。本文将假设 "自由 "一词指向两种自由:身体和精神自由。前者包括行动的自由或工作的自由;后者包括言论自由、宗教自由或思想和表达的自由。现代社会普遍更加强调精神自由,但身体自由往往是精神自由的基础。通过对古代中国、印度和欧洲启蒙运动的案例研究,本文将探讨身体和精神自由的重要性。

例1:中国的春秋时期

在中国古代,春秋时期见证了哲学和政治理论的蓬勃发展。从公元前770年到公元前476年,这段战乱不断的时期不存在单一的政治力量或政权的控制。不同的势力之间存在着长期的不确定性和相互的战争。事实证明,这样的混乱间接有利于先锋思想家和社会实验者获得影响力。这一时段见证了前所未有的突破性哲学的爆发,以至于中国历史学家将其称为 "百家争鸣 "的时代。

虽然某些风险被放大了,但春秋时期的哲学家和理论家拥有身体自由。也就是说,他们可以在中国各地游历,而不会面临被囚禁或大规模政治迫害的人身风险。例如,从公元前497年到公元前483年,孔子游历了大多数主要国家。在这14年的广泛旅行中,孔子这个以其对政治的深刻评论而闻名的人,在身体自由方面没有遇到重大限制。他曾被不同的国家俘虏,但这些俘虏通常都很短,并没有对他的政治生涯留下持久的影响。当时的中国给予这种身体自由,正是因为没有政治或军事霸权,没有一个国家可以对广大地区或像孔子这样的学者的行动进行完全控制。

身体自由是 "百家争鸣 "出现的一个不可或缺的因素。首先,一个人只有在身体允许和有能力活动的情况下才能寻找启发。再以孔子为例,在他广泛游历中国期间,他从许多同时期思想家和各领域的大师那里寻求灵感。例如孔子拜访了老子,道家学派中最重要的哲学家。他与老子的会面部分解释了儒家学派和道家学派之间的相似之处。孔子从道家思想中汲取了一些思想,并相应地调整了他的思考。比如,孔子认为,人们的自然 "道德 "应该是任何形式的统治的基础。这种对 "道德 "的强调可以追溯到老子提出的一个论点,即这个世界上的每一种模式或创造都是某种自然秩序的结果,人们在做决定时应该遵循这种“道”的秩序。从这个例子可以看出,孔子能够使他的思想体系具有公认的重要性,这要归功于他的身体自由允许他访问不同地区和不同群体。

其次,身体自由是必须的,因为它为思想家们提供了传播其思想的平台。孔子周游列国,推广儒家学说,正是因为他有行动的选择。正如《论语》所记载,孔子在许多不同的国家教授了无数的学生。

中国春秋时期的哲学家们也拥有精神上的自由。也就是说,他们有自由提出独特的意见,并以任何合适的方式表达出来。当时没有一个强大的中央权力机构可以在广大地区支配思想,“百家争鸣 "一词正是证明了中国思想家所经历的精神自由程度。例如,有一个学派是 "法家学派"。这个学派认为,最有效的统治方式是通过严格的法律条文和严酷的惩罚。然而,另一个主流思想流派是 "道家学派"。倡导道家学派的人认为,最好是遵循自然界的模式,拒绝过多的人工设计。这两个学派直接对立,但它们大致在同一时期内共存。它们的共存是由于普遍缺乏可以钳制表达自由的中央集权。

精神自由对中国的哲学家们来说是至关重要的。人们可以把精神自由视为开拓思想的基石。如果对言论或思想加以限制,就很难想象孔子会提出他对人性和政治结构的开创性意见,因为他会更谨慎,害怕表达政治上的错误观点。此外,一个想法只有在能够给更多的受众或社会带来某种形式的影响时,才能变得具有先锋性。精神上的自由给思想插上了飞翔的翅膀,这将防止这些思想盲目地符合既定的社会秩序。从过去到现在的专制国家都限制了精神自由,这就把思想钉在了教条式的社会结构上,使其难以产生社会活力或创新精神。“百家争鸣 "中的大多数主要流派都能发表超越性的言论,完全重新构建社会秩序,这要归功于相对更纯粹的精神自由。

例2:释迦牟尼和佛教

轴心时代的另一个值得关注的文化是古印度。其中一个见证了创造性哲学爆发的时期是在公元前6-5世纪。这一时期印度哲学的领军人物是一位名叫释迦牟尼的王子,或更多地被称为佛陀。他被认为是佛教的创始人,佛教是一种追求自由的宗教,特别是精神自由。

释迦牟尼出生在一个豪华的皇宫里,起初并没有什么身体自由。他不被允许,直到29岁时才离开皇宫。虽然他享受着受保护的生活,但身体自由的缺乏和奢华的生活方式使他的精神状态受到了负面影响。随着岁月的流逝,释迦摩尼感到精神上的空虚。他感受不到周围环境的复杂本质,所以他没有任何灵感来填补他头脑中的空白。

幸运的是,在30岁时,释迦摩尼最终获得了身体自由。根据佛教传统,一天晚上他决定自己离开宫殿去散步。敦促他离开皇宫的可能是他那颗渴望自由、渴望观察现实的心。从那时起,释迦牟尼就再也没有回过他的宫殿,他的余生都在尼泊尔、印度和斯里兰卡各地游历。

(释迦摩尼与他的四次观察)

事实证明,身体上的自由对释迦牟尼达到开悟的目的至关重要。就像孔子一样,释迦摩尼利用他的身体自由来寻找灵感。例如,他的冥想侧重于解决他对人类痛苦和欲望的疑问。然而,他是根据对周围环境的四次真实观察而提出这些问题的。在他离开皇宫后不久,他看到一个因年老而驼背的人,一个被疾病折磨的人,一具死尸,以及一个流浪的苦行者。这些景象促使他思考为什么会发生痛苦以及如何减轻痛苦。在旅途中,释迦牟尼遇到了一些著名的哲学老师。这些老师向他传授了印度及其周边地区普遍存在的宗教和信仰。虽然释迦牟尼对自己被教的知识并不知足,但与这些老师的课程确实让他有了更全面的思想。如果没有身体上的自由,这些灵感大多不会被发现,而通往启蒙的道路也会更加曲折。

与身体上的自由不同,释迦牟尼有一种与生俱来的精神自由,无法被禁锢。毋庸置疑,他所处的环境为他提供了必要的条件,使他能够自由地探索、制定和表达意见或信仰。但是,释迦牟尼的启蒙之旅的真正动力是他自己对求知的不可抗拒的渴望,以及他不轻易服从任何思想体系的意愿。当他的父亲把他“囚禁”在宫殿里时,他不愿意让自己的精神落入空虚之中。他对宫外的真实世界总是有这种隐秘的好奇心和敏锐的目光。在他的一生中,释迦摩尼始终保持着心灵的洁净,这使他能够进入一种纯粹的冥想状态。

释迦牟尼的精神自由塑造了他的思想,凝聚成佛教。佛教在许多方面与其他普及性宗教有很大的不同。例如,佛教更集中于人性和生命的自然循环。佛教不神化其创始人或任何圣人,而是讲授他们的生活史以及他们如何现实地开悟。换句话说,佛教是一个对现实中的真实元素投入更多关注的宗教。人们可以把这些独特的方面归功于释迦牟尼的精神自由,这使他能够跳出边框,内在地关注客观的现实,而不过于顾忌总体的社会规范。

例三:启蒙运动及其思想家

正如前文所述,亚里士多德可以被视为西方历史上最伟大的知识分子之一,他在学术界的许多领域进行了开创性的工作。他开辟了西方审慎研究、推理和对现实完整观察的传统。由于身体和精神上的自由,亚里士多德可以在这么多领域创造出杰出的作品。大约2000年后,在17世纪的欧洲,出现了类似的新哲学和理论的爆发,这个爆发被称为启蒙时代。

16和17世纪的欧洲被持续的战争所困扰,如荷兰起义(八十年战争)或1618至1648年臭名昭著的三十年战争。这些战争破坏了欧洲的稳定局势,出现了许多权力的转移。例如,16世纪见证了西班牙的衰落以及法国和英国的相继崛起。这些权力的转移确保了没有一个王国或帝国有能力控制欧洲的广大地区,也确保了文化的强烈多样性。

当时的哲学家和作家们间接地从这种混乱中受益。就像中国春秋时期的思想家一样,这些欧洲学者享有一定程度的人身自由。以约翰-洛克为例,他是那个时代最有影响力的思想家之一。约翰-洛克一生中大部分时间都在他的出生地英国度过。17世纪的英国是一个动荡不安的地方,王室和想要建立共和国的政治家之间为权力而战。虽然洛克是政治的热心参与者,但这种情况几乎对他有利,因为他可以表达他对政府的开创性想法,而不必过分担心被监禁。

拥有身体自由又使约翰-洛克能够寻求灵感和当代思想家的思想。在他作为学生的几年里,洛克可以在英国各地旅行,学习知识。例如,在牛津大学基督教堂,洛克迷恋上了勒内-笛卡尔的作品,激励他深入研究实验哲学和文科。1667年,洛克前往伦敦,会见了沙夫茨伯里第一伯爵安东尼-阿什利-库珀。安东尼-阿什利-库珀对洛克的政治观点留下了深刻的影响,并鼓励他创作一些最引人注目的著作,包括《政府论》。如果没有人身自由,洛克可能不会遇到这些有影响力的人物,在他的思想体系中留下如此积极的印记。

启蒙思想家们也经历了一个相对精神自由的时代。欧洲许多地方,如法国,其政治、经济和社会生活的结构都在发生深刻的变化。转型时期对思想和表达自由的打压较少。法国思想家让-雅克-卢梭就是一个典型的例子。卢梭出生于1712年,他生命中的大部分时间是在路易十六的统治下度过的。路易十六时期的法国社会充满了不同社会群体之间的高度紧张和冲突。正是在这种紧张的环境下,卢梭找到了空间和自由,提出了他对民主政府和 "共同意志 "的开创性观点。他新颖的政府结构的预想预示着法国大革命和欧洲政治从君主制向民主制的更大转变。

卢梭和其他大多数启蒙思想家的精神自由被证明对他们的思想产生更大的影响至关重要。只有在精神自由的情况下,这些启蒙哲学家才有胆量真正尝试提出有关政治和自由艺术的开拓性概念。例如,卢梭的 "共同意志 "和 "直接民主 "的概念可以成为激进的法国大革命的基石,得益于这些想法对于未知领域的深入挖掘,并且在本质上具有的超脱想象力。例如,在《社会契约论》的一个章节中,卢梭创造性地认为革命在许多方面是不可避免的,他写道:"在暴力时期......当革命对人民的作用就像某些危机对个人的作用一样,当过去的恐怖取代了遗忘,被内战点燃的国家可以说是从灰烬中重生,在逃离死亡的怀抱中恢复了青春的活力。" 这些敦促许多人重新思考历史和政治的论点只有在卢梭的精神自由下才会出现。

结语

总的来说,这篇文章说明了思想大爆发时代发生的两个先决条件是思想家具备的身体自由和精神自由。此外,通过对历史上最有影响力的杰出思想家和时间段的案例研究,可以看出这两种自由具有巨大的潜在力量。对于个人而言,保持身心自由要将双脚踏入真实的土地,要对世界产生真切的关怀。对于社会而言,激发社会最基础原动力要营造自由而宽容的环境,鼓励培养思想多样性。然而,应该注意的是,社会必须对精神自由特别加以约束。当哲学家们拥有表达自己思想的完全自由时,可能往往会导致有害的极端主义。政治家们与社会学者正是通过在专制主义和极度自由主义之间的不断试验和摇摆中才能实现宏观的平衡。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/596

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权