The Quest for Infallibility: Part II 对无误信息的追求:第II部分

The Quest for Infallibility: Part II

Introduction

The last article established that the “quest for infallibility,” to strengthen stories or seek the relative truth, has been undertaken by societies for the past two millennia. When the term “infallibility” is discussed within such essays, it does not necessarily denote an errorless state. Instead, more precisely, infallibility means a state in which the actions of fallible humans are put to the sidelines and their impacts minimized, in which societies appeal to some natural force or mechanism that always delivers for the “public good.” This essayist highlighted two main methods people have been experimenting with to achieve infallibility: Taking humans out of the loop and creating a “free market of information.”

This and the following articles shall continue the exploration of humans’ obsession with infallibility. They will extract and isolate a particular moment or relationship in this quest: How does the search for infallibility through these methods induce social dynamism and profound implications for society's constituents? Using the example of Adam Smith’s economics, this essay hopes to illustrate two significant social consequences of the quest for infallibility. First, achieving infallibility almost inadvertently masks fallible human decisions and mechanisms. Second, the pursuit of infallibility alters power distribution and gives way to the rise of new fallible social groups, often bringing about further ramifications.

Infallible Free Markets

Adam Smith, the renowned Classical economist, is revered for his work that proposes and advocates for a “free market” with minimal human intervention. Free markets motivate individuals, acting in their self-interest, to produce what is societally necessary, thereby promoting the public good. While Smith’s theories on the free market hold irreplaceable, applicative significance for the field of economics, in the context of this essay, they can also be understood as an appeal to infallibility – or, more specifically, an infallible mechanism. Now, Smith himself recognizes the limitations and errors in this set of theories. For example, he acknowledges the existence of market failures due to a lack of intervention and, consequently, the government’s role in correcting them. However, suppose one understands infallibility as defined above. In that case, Smith’s theories do try to minimize the role of fallible humans in regulating an economy, and they certainly do appeal to a seemingly natural mechanism that acts for common benevolence.

Smith’s appeal to infallibility comes across in many of his claims. First, though Smith rarely quotes the exact wording of an “invisible hand,” he writes about it as an infallible market force that works through individuals making self-interest-based economic decisions. In Book IV, Chapter II of hisThe Wealth of Nations, he famously explained, “By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.” This notion operates through several mechanisms. Self-interested individuals bring innovation and new ideas to the table to outperform competitive rivals, increasing productivity and, thus, overall prosperity. By acting out of selfishness, individuals also allow market competition to regulate behavior and remove inefficiencies. For instance, if a company produces goods of subpar quality, consumers, deciding for their well-being, will shift to better alternatives. If a company has lower productive efficiency than its competitors, it will receive smaller profits and potentially shut down. Smith adopts a naturalistic view in this system that markets “naturally” correct themselves without much human intervention as if guided by the invisible hand, infallibly aligning individual interests with the public good.

Second, Smith uses an infallible trade mechanism to present free trade as an inevitable good. InThe Wealth of Nations, before the time of David Ricardo, Smith already hinted at the concept of “comparative advantage” by writing: “What is prudence in the conduct of every private family can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage.” This quote suggests that if economies do not impose trade restrictions and instead rely on this universal, infallible trade mechanism based on comparative advantage, then “cheaper” commodities would flow between them. Smith further argues to minimize the role of governments in trade, as he contends that they are “conscious to themselves that they knew nothing about the matter.” Therefore, Smith declares that that “the sovereign…must always be exposed to innumerable delusions” in the execution of a task “for the proper performance of which no human wisdom or knowledge could ever be sufficient.” By minimizing the intervention of fallible parliaments and officials, and by resorting to the infallible mechanism of free trade, multilateral economic prosperity may be eventually achieved.

Unfortunately, both of the aforementioned appeals to infallibility masked significantly fallible human mechanisms and decisions. When Smith elaborated upon the omnipotence of the free market, he was misleading in the sense that his model failed to account for the existence and impacts of human errors and wrongdoings. For example, his model did not factor in externalities and environmental costs – realities that contradict the notion of a naturally self-correcting market. Additionally, by assuming that all market participants, guided by their own self-interest, acted rationally with relative equal ability to negotiate, Smith masked the mechanism of systemic inequalities, such as employer-employee power imbalances, which was undoubtedly a demonstration of human fallibility. This appeal to infallibility, though lucrative it appears, conceals many fallible processes and decisions that could result in market failure or generate negative social ramifications.

Similarly, when Smith presented free trade as an inevitable good and infallible mechanism that leads to co-prosperity, he masked human fallibility in the international system. For instance, he masked the possibility of developing economies being exploited by stronger industrial powers in free trade, resulting in unequal gains. The examples of the Opium Wars or the U.S. trade agreements in Latin America during the 1990s demonstrate that the seemingly utopic vision of free trade can be used to establish economic dominance over weaker nations. This exploitation process may be considered a human error, a failure to develop guardrails and international regulations to deter and prevent the larger economies from infringing upon the interests of the smaller ones. Unfortunately, by claiming that comparative advantage shall always work its magic and framing free trade as an infallibly beneficial mechanism for participating nations, Smith could mislead economies to overlook the dangers of this system due to the fallible nature of its human designers.

The Social Impacts of Smith’s Theories

Like how theBibleled to the rise of a new rabbi institution, Smith’s appeal to infallible free markets engendered the growth of new fallible social groups, mainly bankers and financial elites. Smith’s hymn for the bonanza of economic freedom and his scathing criticisms of large-scale government intervention inadvertently created the fitting environment for the dawn of “free banking.” As his theory of free markets gained popularity across Europe and beyond, an increasing number of firms and institutions began to acquire factors of production, especially capital, to pursue their self-interests and make profits in the market. Thus, in Smith’s view, banking plays a critical role in channeling idle capital into productive uses, such as funding entrepreneurship, thereby contributing to the expansion of free markets. In Book II, Chapter II ofThe Wealth of Nations, Smith argues “the judicious operations of banking enable capital to be active and productive, by substituting paper in place of gold and silver.”

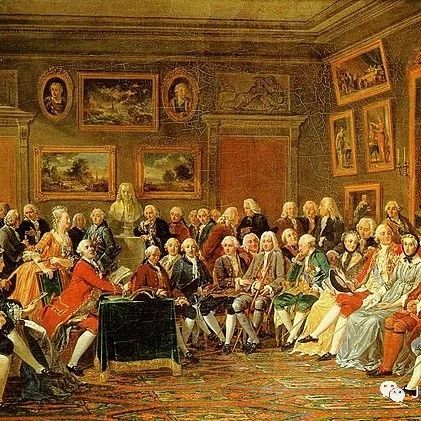

Banks and bankers themselves fit into the larger narrative of the infallible free market. Banks are involved in the market for loanable funds. After Smith argued for the removal of government intervention in markets, bankers were beneficiaries as they could now freely act out of self-interest, just like any other party. In England, for example, the Bank of England was founded, and joint-stock banks emerged, allowing investors to buy shares and quickly move capital around. In the U.S., the Bank of North America, the Bank of New York, the Bank of Massachusetts, and the Bank of the United States emerged one after another. Before the age of classical economics heralded by Smith, banks existed, but they could not develop due to limited monetization and the absence of free markets for loanable funds. Hence, by appealing to the power of infallible markets, Smith helped usher in a new age defined by a rising demand for capital, bringing about an age of development for the banking industry.

Similar to how the rise of the rabbis further introduced profound social ramifications as power distributions changed, the rise of banks presented novel challenges to societies at the time. Most markedly, while competition is a core tenet of Smith’s economic philosophy, as banks held more significant sway over allocating funds and resources, some profitable ones evolved into monopolists and oligopolists, distorting credit flows and leading to economic inefficiency. Smith also failed to foresee the role of banks in encouraging speculative lending or mismanagement of capital, causing financial instability, such as bubbles or crashes. The case of Smith’s economics and the birth of large-scale, powerful banks reveals, once again, one of the fundamental principles behind humans’ quest for infallibility: Infallibility not only masks the mistakes, biases, and ignorance of fallible humans, but also gives way to the rise of new fallible social groups that may reshuffle the composition of governments and societies.

《对无误信息的追求:第II部分》

导言

上一篇文章指出,在过去的两千多年里,社会一直在追求绝无错误的信息,以强化虚构故事或寻求相对真理。在此类文章中讨论“无误性”一词时,作者并不一定指一种完全无误的状态。相反,更确切地说,“无误信息”是指一种状态,在这种状态中,易犯错的人类的行为被置于次要地位,其影响被降到最低,社会诉诸于某种自然力量或机制,而这种力量或机制总是能够实现“公共利益”。作者强调了人们为实现万无一失而尝试的两种主要方法:让人类脱离信息循环,以及创建一个“信息自由市场”。

这篇文章和接下来的文章将继续探讨人类对无误信息的痴迷。它们将提取出这一追求的过程中这一特定时刻或关系:通过这些方法寻求绝无错误的信息是如何促使社会变动并对社会组成部分产生深远影响的?本文以亚当-斯密的经济学为例,希望说明追求无误信息的两个重要社会后果。首先,追求绝无错误的信息几乎一定会无意中掩盖人类决策和机制的谬误。其次,对无误性的追求会改变权力分配,并导致新的易犯错的社会群体的崛起,这往往会带来更为深远的宏观后果。

绝无错误的自由市场

亚当-斯密是著名的古典经济学家,他的著作提出并主张建立一个人为干预最少的“自由市场”,因而备受推崇。自由市场激励个人从自身利益出发,生产社会所需的产品,从而促进公共利益。虽然斯密关于自由市场的理论对经济学领域具有不可替代的应用意义,但在本文的语境中,这些理论也可以被理解为对无误信息的追求--或者更具体地说,对一个无误机制的追求。诚然,斯密自己也承认这套理论存在局限性与错误。例如,他承认由于缺乏干预而存在市场失灵,因此,政府在纠正市场失灵方面发挥着作用。然而,假设人们按照上述定义来理解无误性,那在这种情况下,斯密的理论确实试图最大限度地减少易错的人类在调节经济中的作用。并且,这些理论也确实诉诸于一种看似自然的机制,这种机制为社会整体的福祉而运动。

斯密对无误性的诉求体现在他的许多主张中。首先,尽管斯密很少引用“看不见的手”此确切措辞,但他在书中将其描述为一种通过个人做出基于自身利益的经济决策而发挥作用的无误的市场力量。在《国富论》第四卷第二章中,他有一个著名的解释:“通过追求自己的利益,个体促进社会利益的效果往往比他真正打算促进社会利益时的效果更好”。这一概念通过几种机制发挥作用。利己的个人会带来创新和新想法,从而试图超越竞争对手,提高生产率,进而促进整体繁荣。个人出于私利行事,也能让市场竞争规范行为,消除低效。例如,如果一家公司生产的商品质量不佳,消费者在决定自己的福祉时,就会转向更好的替代品。如果一家公司的生产效率低于竞争对手,那么它就会获得较少的利润,并有可能倒闭。斯密在这一体系中采用了一种自然主义观点,即市场“自然”地自我纠正,不需要太多的人为干预,就像有一只看不见的手在指引着,使个人利益与公共利益始终完美地结合在一起。

其次,斯密提到了一种无误的贸易机制,把自由贸易说成是一种必然的福利。在大卫-李嘉图时代之前,斯密在《国富论》中已经暗示了“比较优势”的概念,他写道“如果外国能以比我们自己制造更便宜的价格向我们提供某种商品,那么最好用我们自己工业的一部分产品,以我们具有某种优势的方式向他们购买”。这句话表明,如果各经济体不施加贸易限制,而是依靠这种基于比较优势的普遍的、无懈可击的贸易机制,那么“更便宜的”商品就会在它们之间流动。斯密进一步主张尽量减少政府在贸易中的作用,因为他认为政府“自知对此事一无所知”。因此,斯密宣称,“主权者......在执行一项‘人类的智慧或知识都不足以正确完成的任务’时,必须始终面临无数的错觉”。通过最大限度地减少不可靠的议会和官员的干预,并借助自由贸易这一无误的机制,多边经济繁荣可能最终得以实现。

遗憾的是,上述两种对无误信息的呼吁都掩盖了人类机制和决策的重大缺陷。斯密在阐述自由市场的万能时,误导了人们,因为他的模型没有考虑到人类错误和过失的存在及影响。例如,他的模型没有考虑外在性或环境成本--这些经济现实与自然自我纠正的市场概念相矛盾。此外,斯密假定所有市场参与者都以自身利益为导向,理性行事,具有相对平等的谈判能力,这就掩盖了系统性不平等的机制,如雇主与雇员之间的权力失衡,而这无疑是人类设计系统时出错的表现。这种对无误性的诉求虽然看起来十分乌托邦式,但却掩盖了许多可能导致市场失灵或产生负面社会影响的错误过程与决策。

同样,当斯密把自由贸易说成是导致共同繁荣的不可避免的福利与无误的机制时,他掩盖了国际体系中人性的弱点与错误。例如,他掩盖了发展中经济体在自由贸易中被工业强国剥削,导致收益不平等的可能性。鸦片战争或20世纪90年代美国在拉丁美洲的贸易协定的例子表明,看似乌托邦式的自由贸易愿景可以用来建立对弱国的经济统治。这种剥削过程可以被认为是人为的错误,即人们没有制定防范措施和国际法规来阻止较大经济体侵犯较小经济体的利益。不幸的是,斯密宣称比较优势将永远发挥其魔力,并将自由贸易描绘成一种对参与国绝对有利的机制,这可能会误导经济体忽视这一体系的危险性,因为其设计者的人性是容易犯错的。

斯密理论的社会影响

就像《圣经》导致了新的拉比机构的兴起一样,斯密对无误的自由市场的呼吁也催生了新的易犯错的社会群体,主要是银行家与金融精英。斯密对经济自由的赞美及对政府大规模干预的严厉批评,无意中为“自由银行”的崛起创造了适宜的环境。随着他的自由市场理论在欧洲和其他地区的普及,越来越多的企业、机构涌入开辟新的市场,开始获取生产要素,特别是资本,以追求自身利益并在市场中获利。因此,在斯密看来,银行业在引导闲置资本用于生产性用途(如资助创业)方面发挥着至关重要的作用,从而促进了自由市场的扩张。在《国富论》第二卷第二章中,斯密认为,“银行业的明智运作通过以纸张代替金银,使资本得以活跃和具有生产性”。

银行和银行家本身也是无误的自由市场的一部分。银行参与了可贷资金市场,在斯密主张取消政府对市场的干预之后,银行家成为受益者,因为他们现在可以像其他各方一样,出于自身利益自由行事。例如,英国成立了英格兰银行,出现了股份制银行,投资者可以购买股票,迅速转移资金。在美国,北美银行、纽约银行、马萨诸塞银行和美国银行相继出现。在斯密所预言的古典经济学时代到来之前,银行是存在的,但由于货币化程度有限以及缺乏可借贷资金的自由市场,银行无法发展起来。因此,斯密借助所谓无误的市场力量,开创了一个资本需求不断增长的新时代,带来了银行业的腾飞。

随着权力分配的变化,拉比的崛起进一步带来了深刻的社会影响,与此类似,银行的崛起也给当时的社会带来了新的挑战。最明显的是,虽然竞争是斯密经济哲学的核心信条,但随着银行在资金和资源分配方面掌握了更大的话语权,一些盈利的银行演变成了垄断者和大型寡头,扭曲了信贷流动,导致经济效率低下。斯密也没有预见到银行在鼓励投机性借贷或资本管理不善方面的作用,从而导致金融不稳定,如泡沫或突然的崩溃。斯密经济学与大规模、强大银行的诞生再次揭示了人类追求无误信心背后的一个基本原则:此追求不仅会掩盖人类的错误、偏见与无知,还会导致新的,易错的社会群体的崛起,从而重新定义政府与更为广泛的社会的构成。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/654

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权