Links Between East and West 58 - Quanzhou 东西方的连接58 - 泉州

(The author in front of the exhibition space at the Quanzhou Museum of Overseas Communication History)

Introduction

During the fourteenth century, a friar, Giovanni da Marignolli, traveled to the Mongol Empire and modern-day China to observe Chinese social traditions and spread Catholic doctrines. In one note in his work, The Travels of Giovanni da Marignolli, he details a city called “Zayton” on the southern coast of China, “There is Zayton also, a wondrous fine seaport and a city of incredible size, where our Minor Friars have three very fine churches…” The city of Zayton in this passage refers to a city now known as Quanzhou in Fujian Province. Though today, it holds less significance than its neighboring ports like Xiamen, it contains evidence of a prosperous era from the tenth to the fifteenth century, when religions from across Asia and Europe, including Christianity, interacted with each other here.

This essay will examine the era of religious diversity in Quanzhou from the tenth until the fifteenth century. During that period, Quanzhou embraced religions ranging from Christianity and Islam to Buddhism, Manichaeism, Hinduism, and the local animistic beliefs of the “Minnan” people. The incredible coexistence between these religions within a region bounded by a few kilometers in circumference merits an examination of the historical causes of this cultural diversity. Drawing on different historical records and artifacts, this essay will argue that Quanzhou's sheer variety of belief systems rested on these three premises: the pre-establishment of a strong, productive local economy, the formation of a widespread trade network, and the support from government policies.

The Pre-Establishment of a Strong Local Economy

To attract worshippers of different religions to Quanzhou, it first possessed a vibrant, strong economy with tremendous productive capacity. The total population, the number of productive industries, and the level of infrastructure construction are three parameters that one can use to assess the domestic economic growth of Quanzhou.

During the early Sui Dynasty (581-618 C.E.), groups of Chinese from the northern regions began to emigrate to Quanzhou. Consequently, the population grew steadily, supporting a booming city that became a recognized region under the central government. By the Song Dynasty, about three centuries later, primary historical records placed the population estimate at a shocking 500,000 individuals. With such a large population, Quanzhou’s labor force expanded significantly over the Tang and Song Dynasties, allowing it to produce diversified economic goods and services.

Quanzhou’s industrial development was rapid during that period. Chinese merchants invented various methods to achieve scaled and commercialized agricultural goods, textiles, pottery, and porcelain production. Archaeologists have found at least 133 massive pottery and porcelain production facilities dotted across the city, verifying the strength of the flourishing production sector of the economy. Quanzhou porcelain producers in the Dehua region also claimed ownership of the most advanced technologies, boosting productive efficiency and quality.

From the late Tang to early Song Dynasties (tenth century), the local government began to build city walls and canals wide enough to allow the passage of huge boats. During the Five Dynasties (907-979 C.E.), the government launched an initiative to systematically “upgrade” the infrastructure through projects to expand the city walls for a few miles and construct streets within the city. These actions facilitated the growth of smaller communities.

Developing a robust local economy with a considerable population, diversified production of goods, and extensive infrastructure was the prerequisite for religious intercommunication. Such an economy provided long-term economic performance and social harmony stability. Only when a city or state is stable can it draw in and embrace diverse people and cultures. Conversely, in a city with an underdeveloped economy and social unrest, no religious missionary or merchant would be willing to settle there due to fear of constant instability.

(Christian tombstone, Yuan Dynasty)

Additionally, for foreign religions to take root and mingle, their human representatives must be able to establish a sense of community in the city. Thanks to the expansion of infrastructure in Quanzhou, foreigners belonging to different religions and sects could establish communities where they could thrive and give birth to new generations. During the Tang Dynasty, Chinese records illustrate that thousands of Muslims from the modern-day Middle East moved into Quanzhou and founded schools, blocks, and mosques. The city has Islamic tombs, and the descendants of these early Muslims have retained their identity to today. These pieces of evidence show that the inherent economic prosperity of Quanzhou during the Tang and Song Dynasties engendered a situation whereby people from other cultural backgrounds successfully settled down and mingled with the local Chinese. Believers in different religions, such as Manichaeism and Christianity, followed suit and established their communities in the city from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries.

The Development of International Trade

(Trade map showing Quanzhou’s connections with Asian countries and beyond)

Though a firm, the local economy created the fitting setting for different religious interactions; economic trade most directly brought these traders and religious believers together. Quanzhou was the nexus of an expansive trade network. Quanzhou’s trade partners included modern Vietnam, Korea, Indonesia, India, Oman, Sudan, and Kenya at its zenith in power. Quanzhou merchants made essential improvements to the design of their ships to sail long-ranging trade routes. Archaeologists have unearthed massive vessels from the Song Dynasty, over 35 meters long and 10 meters wide. Shipbuilders renovated the sails and oars material to permit long distances sailing over rough waters.

(Ahmad’s gravestone)

This vast network in which Quanzhou played a significant role as a primary importer and exporter of goods provided the platform for international merchants to meet and live together in that city. Many who introduced religion into the region were not missionaries but rather merchants and sailors. In the Quanzhou Museum of Overseas Communication History, one artifact is a gravestone belonging to a Persian trader called “Ahmad.” The gravestone details the Muslim community that traders like himself had constructed, complete with facilities and infrastructure such as schools, roads, and mosques. Without the flourishing international trade, Persians would not have found a powerful enough incentive to settle in Quanzhou; hence, Islam could not have spread in the city.

(Hinduism sculptures and stone inscriptions, Yuan Dynasty)

The same logic applies to traders from India or other southeastern nations that adopted religions like Hinduism or Manichaeism. Records that Hinduism reached Quanzhou from Sri Lanka and India via sea trade routes. Economic profits drove these merchants to export their goods and religions to Quanzhou during the Song and Yuan Dynasties, constituting an age of spectacular diversity and cultural prosperity.

The Support from the Government

During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, the central and local governments were authoritative in determining Quanzhou's policies. In the highly centralized feudal Chinese state, if the government decided to cut off trade with the outside world, then the age of religious diversity would come to an abrupt yet complete end. Thankfully, Song and Yuan emperors and government officials generally supported trading goods and ideas, for it was a period of relative social stability and exponential economic growth. Favorable policies ensured that traders and religious figures could freely engage in intercultural communication and establish long-term settlements in Quanzhou without harmful interference from the government.

Under the rule of Song Dynasty emperors, the government established an efficient and effective set of management institutions for maritime trade. These institutions, directly run by local government officials, organized and oversaw the frequent construction of ports alongside the southern coast, including Quanzhou. One such institution was the Quanzhou Maritime Trade Office, established in 1087. Chinese historians describe this office as “mutually complementary,” meaning that its officers shared a high level of consensus with the civilians on matters concerning the promotion of overseas trade.

(Manichean “Da Li” incomplete tablet, Yuan Dynasty)

To create a more specialized “task force” to monitor and direct maritime trade, Song emperors conferred a title called “The Gentleman of Trust” on citizens who played an instrumental role in inviting foreign merchants to Quanzhou for commercial purposes. Establishing this title or position suggests that Song emperors were willing to delegate some power to civil merchants, allowing their demands to be heard and discussed in the government. Additionally, by incorporating this position into the governmental structure, the Song Dynasty created a political and cultural tradition that the central government would fully commit to developing overseas trade. This vital commitment permitted the flow of goods and religions within Quanzhou. The government provided a free environment to exchange economically and culturally with foreigners.

Conclusion

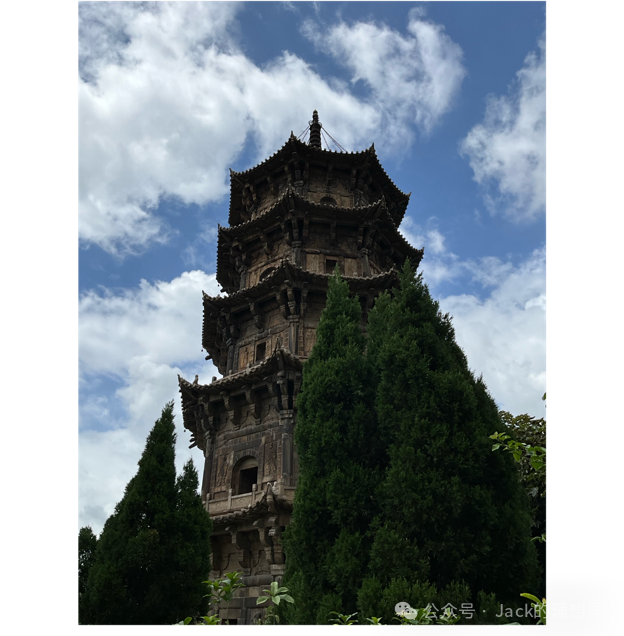

(The Buddhist Kai Yuan Temple in Quanzhou)

This essay attempted to attribute Quanzhou’s religious diversity to three factors: the establishment of a robust domestic economy, the securement of a vast trade network, and the consistent support from the government. Quanzhou’s case demonstrates that cultural interactions often do not occur alone. Instead, they are accompanied by economic and political interactions. With the flow of economic goods, merchants export their religions and cultural values simultaneously. Moreover, the government’s sway over trade and relations with foreign states was immense, especially in ancient China. Therefore, one cannot overstate the role of traders in triggering the explosion of diversity during the Song and Yuan Dynasties. The concerted effort of the government and traders brought about this era of diversity.

Unfortunately, the good times did not last long. Quanzhou suddenly declined since the Yuan Dynasty's end and the Ming's beginning. The population decreased, and merchants left, abandoning their religious buildings. The following essay will explore the reasons for and modern implications of this sudden and precipitous fall.

(作者在泉州海外交通史博物馆展馆内)

简介

14世纪,一位名叫乔瓦尼-达-马里诺利(Giovanni da Marignolli)的修士前往蒙古帝国与中原大陆,观察中国的社会传统并传播天主教教义。在他的著作《乔瓦尼-达-马里诺利游记》中的一篇笔记中,他详细描述了中国南部沿海一座名为 "刺桐 "的城市:"还有刺桐,一座奇妙的海港和一座规模惊人的城市,我们的小修士在那里有三座非常精美的教堂......" 这段话中的刺桐市指的是现在福建省的泉州市。虽然今天它的重要性不如厦门等邻近港口,但它却见证了十世纪到十五世纪的一段繁荣时代,当时包括基督教在内的亚欧宗教在这里相互交融,和谐共存。

本文将探讨泉州从十世纪到十五世纪的宗教多元化时代的特征。在此期间,泉州接纳了从基督教、伊斯兰教到佛教、摩尼教、印度教以及当地闽南人的泛灵论宗教。这些宗教在一个城市中方圆几公里内不可思议地共存,这值得人们对这种宗教文化多样性的历史成因进行研究。本文将根据不同的历史记录与文物,论证泉州信仰体系的多样性是建立在三个前提之上的:一个强大的生产性地方经济的前期建立,一个广泛的贸易网络的形成,以及政府政策的支持。

先期建立强大的地方经济

要吸引不同宗教的信徒来泉州朝拜,泉州首先要拥有一个充满活力、生产能力强大的经济体系。人口总数、生产行业数量与基础设施建设水平是评估泉州内部经济增长的三个参数。

隋朝初期(公元 581-618 年),北方的汉人开始向泉州移民。因此,泉州的人口稳步增长,支撑起一个繁荣的城市,并成为中央政府承认的地区。大约三百年后的宋朝,据主要史料记载,泉州人口达到了惊人的 50 万。由于人口众多,泉州的劳动力在唐宋时期大幅增加,使其能够生产多样化的经济产品和服务。

在此期间,泉州的工业发展迅速。中国商人发明了各种方法来实现农产品、纺织品、陶器和瓷器的规模化及商业化生产。考古学家至少发现了 133 座大型陶器和瓷器生产设施,它们遍布全城,验证了当时经济繁荣的生产部门的实力。泉州德化地区的瓷器生产商还拥有最先进的技术,提高了生产效率、质量。从唐末到宋初(十世纪),当地政府开始修建城墙与运河,其宽度足以让巨型船只通过。五代时期(公元前 907-979 年),政府开始有计划地 "升级 "基础设施,将城墙扩建数英里,并在城内修建街道。这些行动促进了小型社区的发展。

发展强大的地方经济,拥有可观的人口、多样化的商品生产和全面的基础设施,是实现宗教文化繁荣的先决条件。这样的经济可以提供长期的稳定性--无论是在经济表现还是社会和谐方面。只有当一个城市、一个国家保持稳定时,它才能吸引、包容多样化的人群与文化。相反,在一个经济不发达、社会动荡不安的城市,由于担心持续的不稳定,没有宗教传教士或商人愿意在那里安家落户。

(基督教立石墓碑,元代)

此外,外来宗教文化要想扎根和融合,其人类代表必须能够在城市中建立社区意识。在泉州,由于基础设施的扩建,属于不同宗教和教派的外国人可以建立社区,并在其中繁衍生息。根据中国的记载,唐朝时期,成千上万的穆斯林从现代中东地区迁入泉州,建立了学校、街区和清真寺。泉州城内有伊斯兰教墓,这些早期穆斯林的后裔至今仍保留着自己的身份。这些证据表明,唐宋时期泉州固有的经济繁荣造就了另一种文化背景的人成功定居下来并与当地汉人融合的局面。十一世纪至十三世纪,摩尼教与基督教等其他宗教的信徒也纷纷效仿,在泉州建立了各自的社区。

国际贸易的发展

虽然强大的地方经济为不同宗教的互动创造了合适的环境,但最直接将这些商人与宗教信徒联系在一起的还是经济贸易。泉州是一个庞大贸易网络的枢纽,在其鼎盛时期,泉州的贸易伙伴包括现代的越南、韩国、印度尼西亚、印度、阿曼,甚至远至苏丹、肯尼亚。为了在漫长的贸易航线上航行,泉州商人对船只的设计进行了重大改进。考古学家出土了宋代的巨型船只,长 35 米,宽 10 米。造船工人改进了船帆和船桨的材料,以便能在波涛汹涌的海面上远航。

(艾哈迈德的墓碑)

在这个庞大的网络中,泉州作为主要的货物进出口地发挥着重要作用,这为国际商人在泉州会面和共同生活提供了平台。事实上,许多将宗教引入该地区的人并非传教士,而是商人和水手。在泉州海外交流史博物馆中,有一件文物是属于一位名叫 "艾哈迈德 "的波斯商人的墓碑。墓碑详细介绍了像他这样的商人所建造的穆斯林社区,包括学校、道路和清真寺等基础设施。如果没有繁荣的国际贸易,波斯人就不会有足够的动力来到泉州定居,伊斯兰教也就不可能在这座城市传播。

(印度教时刻与碑文,元代)

对于来自印度或其他采用印度教或摩尼教等宗教的东南部国家的商人来说,同样的道理也适用。据记载,印度教通过海上贸易路线从斯里兰卡和印度传入泉州。宋元时期,经济利益驱使这些商人向泉州输出他们的商品和宗教,构成了一个多元化和文化繁荣的时代。

政府的支持

宋元时期,中央和地方政府在决定泉州的管理政策方面发挥着主导作用。在高度集中的中国封建时期,如果政府决定切断与外界的贸易往来,那么宗教多元化时代就会戛然而止。值得庆幸的是,宋元时期的皇帝和政府官员普遍开放地支持商品与思想的贸易,因为这是一个社会相对稳定、经济飞速发展的时期。有利的政策确保了商人和宗教人士可以自由地进行跨文化交流,并在泉州建立长期定居点,而不受政府的负面干预。

在宋朝皇帝的统治下,政府建立了一套高效的海上贸易管理机构。这些机构由当地政府官员直接管理,负责组织和监督包括泉州在内的南部沿海港口的频繁建设。成立于 1087 年的泉州市舶司就是其中之一。中国历史学家将该机构的性质描述为 "相辅相成",这意味着该机构的官员与普通商人在促进海外贸易的问题上达成了高度共识。

(摩尼教“大力”残碑,元代)

为了建立一支更专业化的团队来监督和指导海上贸易,宋朝皇帝授予在邀请外国商人到泉州经商方面发挥重要作用的市民一个称号,叫做 "承信郎"。这一头衔或职位的设立表明,宋朝皇帝愿意将一些权力下放给民间商人,允许他们在政府中表达和讨论自己的诉求。此外,通过将这一职位纳入政府结构,宋朝创造了一种政治和文化传统,即中央政府将全面致力于海外贸易的发展。这一重要承诺允许货物在泉州乃至全中国流通,从而也允许宗教与文化相互共存。政府为与外国人进行经济和文化交流提供了一个自由的环境。

结论

(开元寺)

本文试图将泉州的宗教多样性归因于三个因素:建立强大的地方经济、确保庞大的贸易网络以及政府的一贯政策支持。泉州的案例表明,文化互动往往不是单独发生的。相反,它们与政治经济互动相伴而生。正是随着经济商品的流通,商人们同时输出交流了他们的宗教与文化价值观。此外,特别是在古代中国,政府对贸易和对外关系的控制力是巨大的。因此,人们不能过度强调商人在宋元时期引发多样性爆炸的作用 - 正是政府和商人的共同努力,才造就了如此多元化的一个时代。

遗憾的是,这般盛况不长,元末明初,泉州突然衰败,人口减少,商人离开,宗教建筑被遗弃。下一篇文章将探讨这一突然的急剧衰落背后的原因与现代意义,未完待续…….

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/638

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权