Read History with Jack 47 British Colonialism 跟着Jack读历史47 - 英国殖民主义

From the sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, Britain rose to become the most dominant force in the world. At its height, in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the British Empire was the largest in history, holding sway over more than 400 million people and 35.5 million squared kilometers of land. Its proud citizens were fond of saying that we are “the empire on which the Sun never sets” (Britannica). The British Empire gained such might through imperialism and colonialism, the legacies of which have been significant. Some argue that the economic impacts of colonialism led to an age of economic prosperity for Britain and that the British today live in a heavily developed nation due to depredating others (Acemoglu). However, by investigating the long-term effects on Britain’s internal economy, its trade relationships with other economies, and the overall cost of empire, this essay will show that Britain is significantly poorer today than it would have been without colonialism.

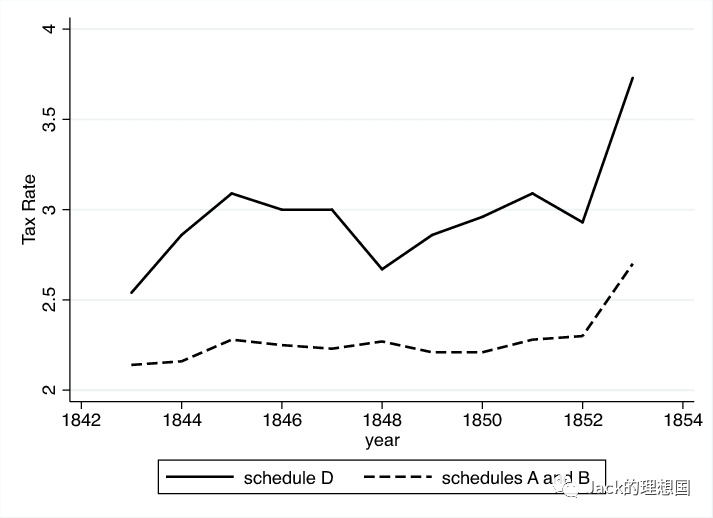

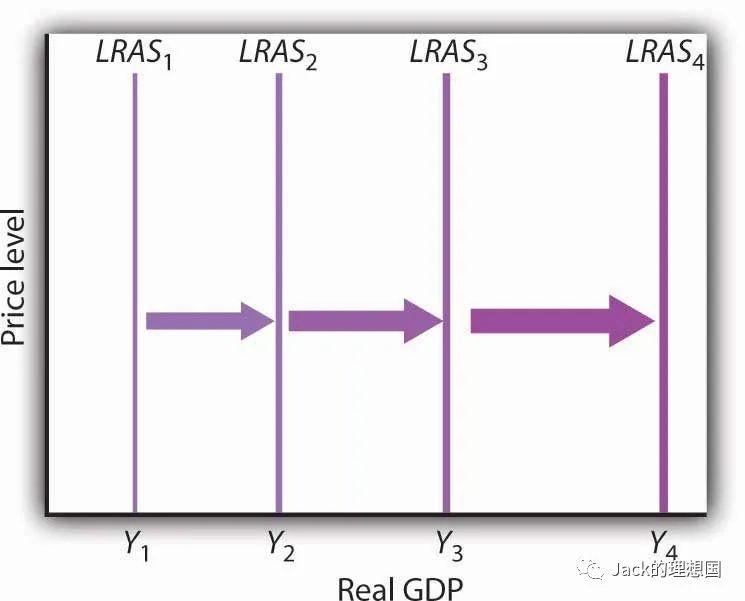

(Graph 1: The Overall Tax Rates of Britain (solid line), from 1843 to 1854)

The long-term economic impacts of colonialism on Britain’s internal economy – namely the assets of individuals and the government – were negative. To fund colonial war efforts, the British government levied hefty taxes on its domestic citizens and its colonies. From the 1780s to around 1850, Britain significantly raised the overall tax rate (see Graph 1) and introduced new taxes, such as the income tax (Mares and Queralt). On the microeconomic level, theoretically, increased levels of taxation lessened the disposable income of the individual, making them less capable of boosting the GDP of Britain through consumption and entrepreneurship. In the long run, the taxes and their drag on economic growth would cause the average British person to possess less wealth than they would have had without colonialism (The Tax Policy Center).

Swayed by nationalistic calls from the government, British entrepreneurs and merchants also invested substantial sums into the colonial effort, hampering wealth accumulation. Patrick O’Brien, an expert on British colonialism, pointed out, “the majority of the English people cheerfully and even proudly [invested in] the empire” (O’Brien). To indirectly encourage colonialism, British investors “chose to send their money overseas” despite facing greater risks and lower average rates of return. Without colonialism, these investors would have put their money towards domestic ventures with lower risk and higher rates of return (Offer). It goes to reason that through continuous wealth accumulation, over the generations, many British today would be richer.

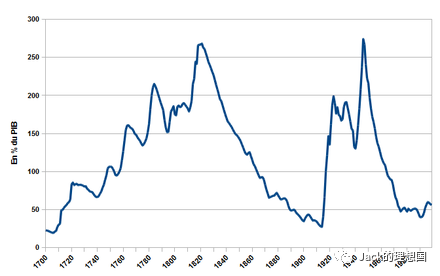

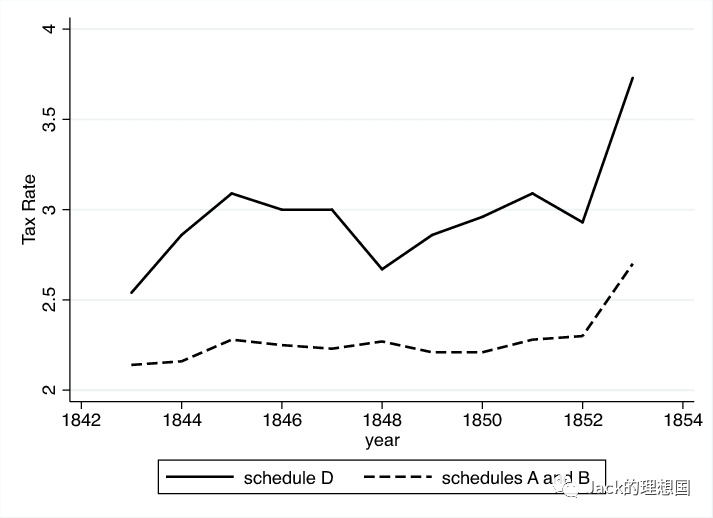

(Graph 2: The Government Debt of Britain as a Percentage of GDP)

On the macro level, the British government spent immense sums to conquer and maintain colonies, making the country poorer overall. Typically, the wealth gained from the colonies did not suffice to pay for colonial adventurism (O’Brien). The government procured the bulk of the funds through borrowing. As shown in Graph 2, the government debt skyrocketed from 1700 to 1820, reaching a whopping 260% of GDP (Gedefr). Although the debt decreased afterwards, the aftershocks of paying off the enormous national debt lingered. As a result of this outlay of funds, Britain underinvested in infrastructure that would have benefitted the local economy, such as schools, hospitals, railroads, and roads (O’Brien). This problem persists, as evidenced by the rather insignificant railroad network in Britain, despite being the first nation to lay tracks (Britannica). This lack of domestic investment due to excessive colonialism impeded the U.K.’s national wealth generation from economic development. Additionally, the detrimental legacy of the debt persisted through the twentieth century as Britain devoted a significant portion of its budget on servicing the debt – money that could have been used to invest in the economy (O’Brien).

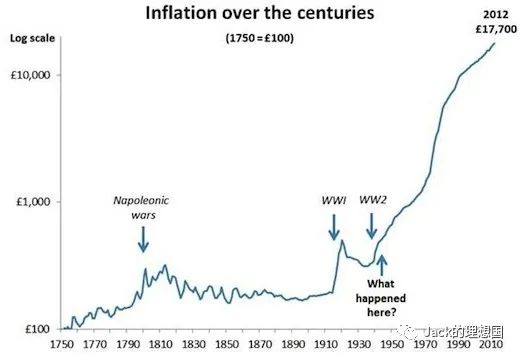

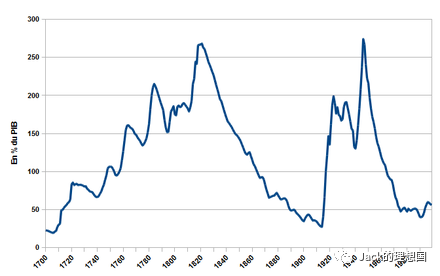

(Graph 3: British inflation from 1750 to 2010)

The negative effect of colonialism on the wealth of Britain’s internal economy is only part of the narrative. Colonialism damaged the relationship between Britain’s economy and other economies, both in Europe and abroad. A look into the British trade account in the eighteenth century, when colonialism rose in significance, is illuminating. Surprisingly, during that time, records show that Britain possessed a trade account surplus (i.e., Britain exported more than imported) (Daudin et al.). This surplus was directly related to colonialism as Britain exported manufactured goods consistently to its colonies and other nations (Andrews). A high share of goods and services being exported, rather than for meeting domestic demand, resulted in a major fall in the supply side of the domestic economy – inflation was a direct consequence (Mankiw). Judging from Graph 3, from 1750 to today, Britain’s inflation rate steadily increased, which can be partially attributed to exporting excessively to colonies (Pettinger). Rising prices impacted the real wealth of British citizens as the purchasing power of money shrank.

The then current account surplus exacerbated the reduced investment in domestic industries. Due to the surplus, the British populace and government could not resist the temptation of exporting goods and services, rather than trying to boost domestic investment (Offer). These two factors combined to negatively impact the growth of national wealth.

The British government’s increasingly aggressive stance of expansionism strained its relationship with other European economies and globally. This strain of relationships led to trade and military conflicts and disputes, disrupting good relations with European powers (O’Brien). For instance, the scramble for resources in Africa and Asia starting from the nineteenth century led to intense competition between the U.K. and other forces such as the United States, France, and Belgium. This scramble for resources can even be argued as being a cause of World War I, in which the British Empire’s might was severely diminished (McQuade). European powers imposed trade barriers on their respective colonies too. The British government specifically imposed high tariffs on French textiles from India, making it difficult for French traders to contest with British merchants (Nye). Through the theory of comparative advantage, trade usually benefits both parties as it increases the potential of consumption (Mankiw). In mercantile economies such as Britain’s, trade has also been historically viewed as a primary method for many to generate wealth by investing in other countries or facilitating the exchange of goods and services (Nye).

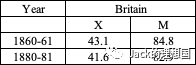

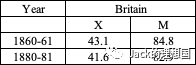

(Table 1: Geographical Distribution of India’s Trade (%))

Therefore, the major disruptions of trade first cut off the possibility for many to start accumulating wealth through trade. One can see this point through the perspective of a significant decrease in both exports and imports to and from a colony. Table 1 displays data showing exactly this, with “X” standing for exports and “M” for imports. The numbers in this table essentially reveal how significant India was as either an importing or exporting colony to Britain (Appleyard). According to this table, from 1860 to 1861, 43.1 percent of India’s total exports went to the U.K., while the goods from Britain took up to 84.8 percent of India’s total imports. However, as trade wars became more intense and trade barriers were set up between the U.K. and other nations, British merchants were discouraged to carry out trading activities. Trade diminished as a result, which is displayed by a drop in both imports and exports in Table 1 (Appleyard). A study of India’s deindustrialization also highlights the international political and economic fragmentation during the nineteenth century as a factor leading to a decrease in trade between India and Britain. The consequence of diminishing trade was that British merchants lacked a means to generate wealth in the long run from these exchanges of goods (Clingingsmith and Williamson).

Admittedly, the opposing argument that the British today are richer thanks to the depredation of colonies does possess some merit. Throughout the process of colonialism, British forces did reap significant economic gain from its colonies (Offer). For instance, U.K. colonies in North America provided the empire with lumber, tobacco, and other materials, while the Indian colony supplied spices, textiles, and gems (Andrews). All these materials were obtained at a relatively lower cost and were used extensively in British factories to produce manufactured goods selling at high prices. Alongside raw materials, the British government also levied hefty taxes from the colonies. For instance, the Townsend Act of 1767 made it possible for the government to tax popular imports from the Thirteen Colonies, such as tea, paper, or lead (Beckett). These tariffs and duties surely helped increase overall government revenue and made it wealthier as time passed. Or it would have, had the Revolutionary War not broken out, forming the United States.

However, while Britain did reap considerable profit from its colonies, it is true that maintaining such a colonial empire came at an immense cost. For instance, Britain funded the development of Hong Kong. The Spectator website points out that the British government provided financial support for British investors in the region. The Manchus, who were at the top of Qing China’s social hierarchy, also received stipends from the British government (Lai). These decisions weighed down the financial and economic development of domestic Britain. Redirecting time and funds from infrastructure investment, education, and social welfare to external ventures, came at the cost of domestic benefit (O’Brien).

To illustrate how Britain would benefit from a hypothetical circumstance without colonialism, consider the situation of roads in Britain during the 1800s. According to a journal titled “Road and Waterway Investment in Britain, 1750-1850”, in certain areas of England, due to the lack of government interference and proper funding, many roads, such as the Holyhead Road suffered from problems relating to “straightening, widening, and reducing gradients” (Ginarlis). The absence of a trust or commissioning organization exacerbated the situation as confusions in terms of road management were common. The essay points out that greater government intervention and funding into road systems would have led to considerable improvement in road conditions and the commercial activities these roads enabled (Ginarlis). Such extra government funding can be diverted from the funds for colonial efforts.

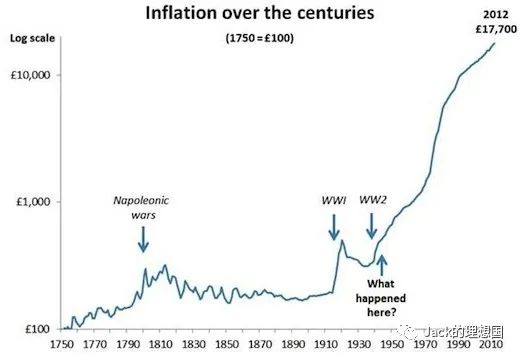

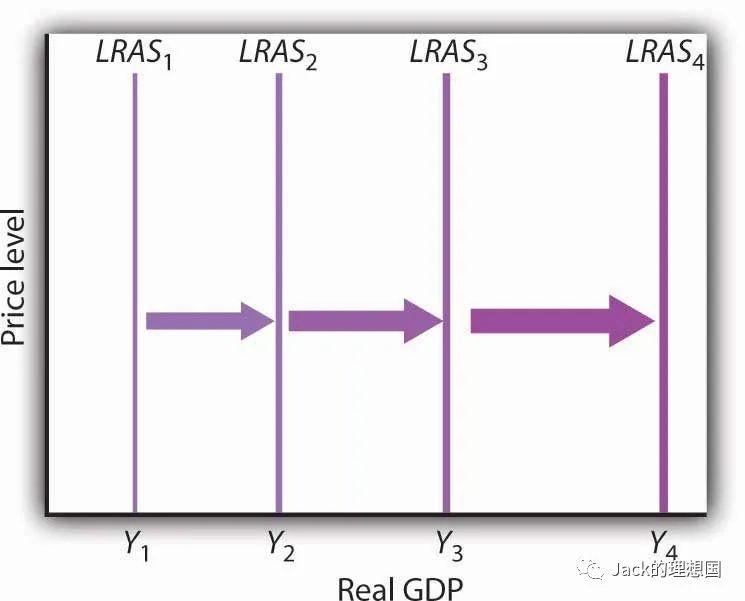

(Graph 4: The AD-AS model showing a rightward shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve)

According to the aggregate demand-aggregate supply (“AD-AS”) model, the long-run aggregate supply curve is affected by labor productivity, level of education, infrastructure, development. If these factors demonstrate positive growth, then the real GDP would increase, shown as a rightward shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve (City University of New York). In the case of the U.K., if the government had chosen domestic investment in basic infrastructure and education over colonialism, its long-run aggregate supply would have risen, leading to real economic growth and the expansion of wealth over time.

Overall, by looking at the long-term blows on Britain’s internal economy and its relationship with other economies in the context of colonialism, Britain is much poorer today than it would have been without colonialism. Not only do these two points have more merit in light of economic theory, but the popular argument for Britain’s exploitation of its colonies (i.e., that Britain procured cheap raw materials and labor) is lacking merit when compared to the costs of maintaining a colonial empire and the potential long-term economic gains of domestic investment. Not that this excuses imperialist ventures. Far from it. It actually demonstrates that, aside from being cruel to native cultures abroad, it is also a bad investment, making it doubly wrong.

An investigation into the economics of a global empire reveal the shocking trade-offs a state faces when it decides to expand its territories for whatever gains. The case of Britain warns leaders of prominent countries today that the bloodstained road of imperialism eventually leaves your citizens worse off. In the current world, to effectively stimulate economic growth and generate wealth for posterity, multilateral cooperation on all levels is still the most reliable, efficient, and fair option for any state engaged in the international order.

Works Cited

Acemoglu, Daron. “The Economic Impact of Colonialism.”Cepr.org, 30 Jan. 2017, cepr.org/voxeu/columns/economic-impact-colonialism. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Andrews, Kenneth.Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480-1630. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Appleyard, Dennis R. “The Terms of Trade between the United Kingdom and British India, 1858ñ1947.”Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 54, no. 3, 2006, pp. 635ñ54. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/500031. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Beckett, J. V. “Land Tax or Excise: The Levying of Taxation in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century England.”The English Historical Review, vol. 100, no. 395, 1985, pp. 285ñ308. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/568625. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "British Empire". Encyclopedia Britannica, 27 Apr. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/British-Empire. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "British Railways". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Mar. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/British-Railways. Accessed 27 June 2023.

City University of New York. “Principles of Macroeconomics 2e, the Aggregate Demand/Aggregate Supply Model, How the AD/as Model Incorporates Growth, Unemployment, and Inflation.”Opened.cuny.edu, 2015, opened.cuny.edu/courseware/lesson/544/overview. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Clingingsmith, David, and Jeffrey Williamson.India’s Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries. 2005, www.tcd.ie/Economics/staff/orourkek/Istanbul/JGWGEHNIndianDeind.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Daudin, Guillaume, et al.Trade and Empire, 1700-1870. 2008, hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03459838/document. HAL Open Science.

Esteban, Javier Cuenca. “The British Balance of Payments, 1772-1820: India Transfers and War Finance.”The Economic History Review, vol. 54, no. 1, 2001, pp. 58ñ86. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3091714. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Gedefr. “British National Debt as a % of GDP 1700-1999.”Schroders.com, 2009.

Ginarlis, John.Road and Waterway Investment in Britain, 1750-1850. 1970, etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/10379/1/537699.pdf. Accessed 4 June 2023.

Lai, George. “Hong Kong and the Surprising Truth about the British Empire.”The Spectator, 18 May 2022, www.spectator.co.uk/article/hong-kong-reveals-the-truth-about-the-british-empire/.

Mankiw, Gregory.Principles of Economics Instructor’s Edition. Cengage, 2012.

Mares, Isabela, and Didac Queralt. “Figure 3: United Kingdom 1843-1853: The Tax Rate of the Traditional...”ResearchGate, ResearchGate, 2015, www.researchgate.net/figure/United-Kingdom-1843-1853-The-tax-Rate-of-the-Traditional-sector-dashed-curve-and_fig2_282803704. Accessed 19 June 2023.

McQuade, Joseph. “Earth Day: Colonialism’s Role in the Overexploitation of Natural Resources.”The Conversation, 18 Apr. 2019, theconversation.com/earth-day-colonialisms-role-in-the-overexploitation-of-natural-resources-113995. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Nye, John Vincent. “The Myth of Free-Trade Britain and Fortress France: Tariffs and Trade in the Nineteenth Century.”The Journal of Economic History, vol. 51, no. 1, 1991, pp. 23-46. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123049. Accessed 19 June 2023.

O’Brien, Patrick K. “The Costs and Benefits of British Imperialism 1846-1914.”Past & Present, no. 120, 1988, pp. 163ñ200. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/650926. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Offer, Avner. “The British Empire, 1870-1914: A Waste of Money?”The Economic History Review, vol. 46, no. 2, 1993, pp. 215ñ38. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2598015. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Pettinger, Tejvan. “History of Inflation in UK.” Economics Help, May 2022, www.economicshelp.org/blog/2647/economics/history-of-inflation-in-uk/. Accessed 19 June 2023.

The Tax Policy Center. “How Do Taxes Affect the Economy in the Long Run?” Taxpolicycenter.org, 2014, www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-do-taxes-affect-economy-long-run#:~:text=Budget%20and%20Economy-,How%20do%20taxes%20affect%20the%20economy%20in%20the%20long%20run,economic%20growth%20by%20increasing%20deficits. Accessed 19 June 2023.

从十六世纪到二十世纪初,英国崛起成为世界上最具统治力的国家。在十九世纪、二十世纪初的鼎盛时期,大英帝国是历史上最庞大的帝国,统治着 4 亿多人口与 3550 万平方公里的土地,其子民自豪地声称自己是 "日不落帝国"的公民。大英帝国通过帝国主义与殖民主义的手段获得了如此强大的力量,而殖民主义行径的遗留则是影响巨大的。一些人认为,殖民主义的经济影响导致英国进入了经济繁荣的时代,即由于掠夺他人,英国人今天生活在一个高度发达的国家。然而,通过调查对英国国内经济的长期影响、英国与其他经济体的贸易关系以及帝国的总体成本,本文将说明今天现实中的英国比假设没有殖民主义的英国是更为贫穷的。

(图 1:1843 年至 1854 年英国的总体税率(实线))

殖民主义对英国国内经济--即个人和政府资产--的长期经济影响是负面的。为了资助殖民战争,英国政府向国内公民和殖民地征收巨额税收。从 17 世纪 80 年代到 1850 年左右,英国大幅提高了总体税率(见图 1),并引入了所得税等新税种。在微观经济层面,从理论上讲,税收水平的提高减少个人的可支配收入,使他们通过消费或投资创业以提高英国国内生产总值的能力下降。从长远来看,税收及其对经济增长的拖累将导致英国普通人拥有的财富少于他们在没有殖民主义的情况下拥有的财富。

受政府民族主义呼声的影响,英国企业家及商人也为殖民努力投入了大量资金,阻碍了财富的积累。英国殖民主义专家帕特里克-奥布莱恩(Patrick O'Brien)指出,"大多数英国人欢呼雀跃,甚至自豪地[投资于]帝国的事业"。为了间接鼓励殖民主义,英国投资者 "选择将资金汇往海外",尽管他们面临着更大的风险与更低的平均回报率。如果没有殖民主义,这些投资者会将资金投入风险较低、回报率较高的国内企业。因此,通过几代人的不断财富积累,今天的许多英国人会因而变得更加富有。

(图 2:英国政府债务占 GDP 的百分比)

从宏观层面来看,英国政府花费巨资征服并维护殖民地,使得国家整体上更加贫穷。通常情况下,从殖民地获得的财富不足以支付殖民冒险主义的工程。政府通过借贷获得了大部分资金。如图 2 所示,从 1700 年到 1820 年,政府债务猛增,高达国内生产总值的 260%。虽然之后债务有所减少,但偿还巨额国债的后遗症却挥之不去。由于这笔资金的支出,英国对学校、医院、铁路和公路等有利于当地经济的基础设施投资不足。尽管英国是第一个铺设铁轨的国家,但其铁路网的规模却微不足道。过度殖民主义导致的国内投资不足阻碍了英国从经济发展中创造国家财富。此外,债务的不利影响一直持续到 二十世纪,因为英国将其预算的很大一部分用于偿还债务,而这些钱本可用于投资经济。

(图 3:1750 年至 2010 年英国的通货膨胀率)

殖民主义对英国国内经济财富的负面影响只是叙述的一部分。殖民主义破坏了英国经济与欧洲及海外其他经济体之间的关系。殖民主义兴起的 18 世纪,英国的贸易账目很有研究意义。令人惊讶的是,当时的记录显示,英国拥有贸易账户盈余(即英国出口多于进口)。这种盈余与殖民主义直接相关,因为英国一直向其殖民地和其他国家出口制成品。高比例的商品和服务出口,而不是用于满足国内需求,导致了国内经济供应方的大幅下降--通货膨胀是直接后果。从图 3 可以看出,从 1750 年至今,英国的通货膨胀率持续上升,部分原因是向殖民地过度出口货品。由于货币购买力下降,物价上涨影响了英国公民的实际财富。同时,当时的账户盈余加剧了国内工业投资的减少。由于盈余,英国民众和政府无法抵制出口商品和服务的诱惑,而不是努力促进国内投资。这两个因素结合在一起,对国家财富的增长产生了负面影响。

英国政府日益激进的扩张主义立场使其与其他欧洲经济体乃至全球的关系紧张。这种紧张的关系导致了贸易和军事冲突与争端,破坏了与欧洲列强的良好关系。例如,从 十九 世纪开始,对非洲和亚洲资源的争夺导致了英国与美国、法国和比利时等其他势力之间的激烈竞争。这种对资源的争夺甚至是第一次世界大战的起因,而大英帝国的实力在这次战争中被重创。欧洲列强也对各自的殖民地设置了贸易壁垒。英国政府特别对来自印度的法国纺织品征收高额关税,使法国商人难以与英国商人竞争。根据比较优势理论,贸易通常对双方都有利,因为它能提高消费潜力。在英国这样的重商经济体中,贸易历来被视为许多人通过投资其他国家或促进商品和服务交换来创造财富的主要方法。

(表 1:印度贸易的地理分布(%))

因此,贸易的重大中断首先切断了许多人通过贸易开始积累财富的可能性。研究者可以从殖民地进出口大幅减少的角度来理解这一点。表 1 显示的数据正好说明了这一观点,其中"X "代表出口,"M "代表进口。表中的数字揭示了印度作为英国进口或出口殖民地的重要性。根据该表,从 1860 年到1861 年,印度出口到英国的商品占印度出口总额的 43.1%,而来自英国的商品占印度进口总额的84.8%。然而,随着贸易战日趋激烈,英国与其他国家之间设置了贸易壁垒,阻碍了英国商人开展贸易活动。贸易因此而减少,表 1中的1880-1881时段进出口下降就说明了这一点。对印度去工业化的研究还强调,19 世纪国际政治和经济的分裂也是导致印度和英国之间贸易减少的一个因素。贸易减少的后果是,从长远来看,英国商人缺乏从商品交换中创造财富的手段。

诚然,诸多研究者认为今天英国人的富裕得益于对殖民地的掠夺,这种观点确实有一定道理。在整个殖民主义过程中,英国势力的确从其殖民地获得了巨大的经济收益。例如,英国在北美的殖民地为帝国提供了木材、烟草和其他材料,而印度殖民地则提供了香料、纺织品和宝石。所有这些材料都以相对较低的成本获得,并被英国工厂广泛用于生产高价销售的制成品。除了原材料,英国政府还向殖民地征收高额税款。例如,1767 年的《汤森法案》(Townsend Act of 1767)使得政府可以对茶叶、纸张或铅等来自 13 个殖民地的热门进口商品征税。随着时间的推移,这些关税肯定有助于增加政府的总体收入,使政府变得更加富裕,尤其如果革命战争没有爆发,美国没有成立,英国也并没有在战争中损失大量的经济霸权。

然而,尽管英国确实从其殖民地获得了可观的利润,但维持这样一个殖民帝国确实需要付出更具有伤害性的代价。例如,英国资助了香港的发展。“旁观者”网站指出,英国政府为该地区的投资者提供大量的财政支持,处于清朝社会顶层的满族人也从英国政府那里获得津贴。这些决定拖累了英国国内的金融和经济发展。将时间和资金从基础设施投资、教育和社会福利转向对外投资,是以牺牲国内利益为代价进行的。

为了说明在没有殖民主义的假设情况下英国将如何受益,19 世纪英国的道路状况是很切题的研究对象。根据一本名为《1750-1850 年英国的道路和水路投资》的期刊,在英国的某些地区,由于缺乏政府干预和适当的资金,许多道路(如霍利黑德路)都存在与 "拉直、拓宽和降低坡度 "有关的问题。由于缺乏信托或委托组织,道路管理混乱的情况十分普遍,从而加剧了这种状况。文章指出,政府加大对道路系统的干预和资金投入,本可以大大改善道路状况,并使这些道路能够开展商业活动。这些额外的政府资金可以从殖民工作的资金中挪用。

(图 4:显示长期总供给曲线右移的 AD-AS 模型)

根据总需求-总供给模型,长期总供给曲线受劳动生产率、教育水平、基础设施发展的影响。如果这些因素呈现正增长,那么实际 GDP 就会增加,表现为长期总供给曲线右移。就英国而言,如果政府在殖民主义时期选择对基础设施和教育进行国内投资,其长期总供给就会增加,从而导致实际经济增长和财富的长期扩张。

总体而言,通过研究殖民主义对英国国内经济的长期打击以及英国与其他经济体的关系,今天的英国比没有殖民主义的英国要贫穷得多。这两点不仅在经济理论上更有价值,而且与维持殖民帝国的成本和缺乏国内投资的长期经济影响相比,英国剥削殖民地的流行论调(即英国获得廉价原材料和劳动力)也缺乏价值。这并不是为帝国主义开脱。远非如此,它实际表明,除了对海外本土文化进行残忍迫害之外,帝国主义与殖民主义也是一种糟糕的投资,因此是双重错误的。

对全球帝国经济学的调查揭示了一个国家在决定扩张领土以获取任何利益时所面临的令人震惊的权衡取舍。英国的案例警示当今著名国家的领导人,帝国主义的血腥之路最终会让国民陷入更恶劣的境地。在当今世界,要想有效刺激经济增长,为后代激烈财富,各层面的多边合作仍然是任何参与国际秩序的国家最可靠、最高效、最公平的选择。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/616

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权