Read History with Jack 48-Bronze Age Collapse 跟着Jack读历史48-青铜时代瓦解

The Late Bronze Age Collapse

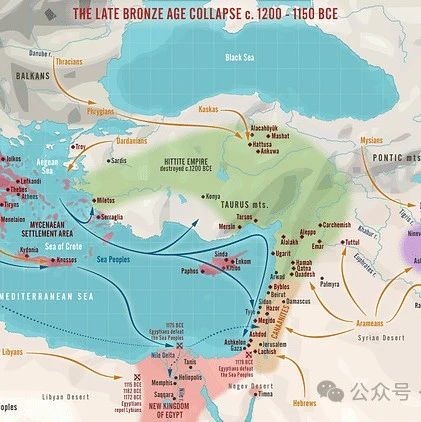

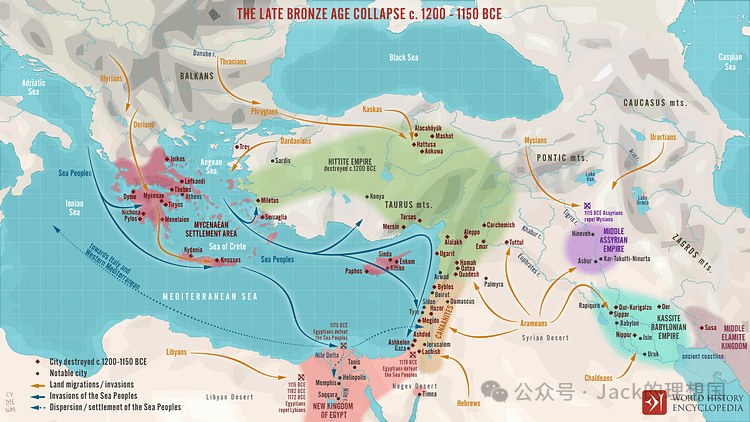

(https://www.worldhistory.org/image/15310/the-late-bronze-age-collapse-c-1200---1150-bce/)

Introduction

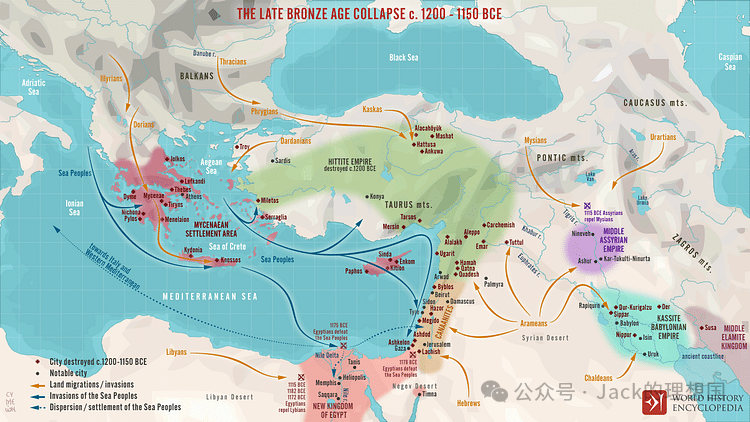

More than 3,200 years ago, the Mediterranean and Near East were home to arguably history’s first “globalized” network. An extended trade system connected the region’s significant powers: the Egyptians, Babylonians, Minoans, Mycenean Greeks, and Hittites, to name a few. Carved ivory trinkets, gold jewelry, and expensive raw materials from differing regions have been exhumed from shipwrecks in the Mediterranean dating to this time. However, while this early period of globalization flourished for more than two centuries, from 1200 to around 1150 B.C.E., it came to an abrupt and mysterious end. By 1150 B.C.E., archaeologists had failed to find convincing evidence to suggest that systematic trade still existed between these nation-states.

The Late Bronze Age Collapse, as this event is known today, is one of history’s most intriguing examples of unpredictable dynamism and changing patterns. Historians still debate about the triggers of this collapse. A popular view is that a range of climatic factors and the invasions of a marauding group of nomads – the “Sea Peoples” – produced a sudden, fatal blow to the system’s equilibrium. This essay will reappraise this popular view and argue that while these external “X-factors” might be necessary to an extent, the problematic internal economic and political conditions of the nation-states involved in this network should be viewed as a more crucial factor that led to its break-up.

Low and Ineffective Levels of Economic Centralization

Since the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean network relied on continuous economic trade as its lifeline, its collapse could have been closely tied to the deteriorating conditions of the involved economies. To examine this point in further depth, one can consider the economic structures of the two powerhouses of the Late Bronze Age world: Mycenean Greece (c. 1750-1050 B.C.E.) and pharaonic New Kingdom Egypt (c. 1550-1070 B.C.E.).

The government exhibited little evidence of centralized control over the agricultural economy of the Mycenean Greek state, situated on mainland Greece and some of the surrounding Aegean islands. As Paul Halstead, a renowned archaeologist and expert, claims, “a significant proportion of the food staples…came in from producers who worked their land ‘independently.’” This quote suggests that the central governors of the Mycenean state, who resided in the palaces, either showed no desire or failed to maintain control over the crucial agricultural production on its land.

The lack of economic centralization can be attributed to the high administrative costs of managing and reducing risks. The climate that the Myceneans faced was quite unpredictable. If a drought hits and results in crop failure, the authorities must “financially” bail smaller farmers out or provide them access to more production factors (especially capital and labor), which might significantly increase productivity. However, both solutions entailed a rising administrative cost, requiring massive efforts to assess and deliberate upon the relief plan that shall be implemented, especially given the frequency of random natural calamities. Therefore, the officials in power gradually found it increasingly challenging to oversee economic performance. They allowed agricultural production to be divided into small segmentary units.

Similarly, Egypt’s economy suffered from a weak grip by the pharaohs and their officials. An intriguing study conducted by the Stanford Humanities Center follows the distribution of Egyptian labor wages: beer and bread. The changes and distributions in these labor wages can be highly indicative of the conditions in the Egyptian economy back then, as beer and bread were necessities that formed the cornerstones. By using the method of “volumetric standardization,” the study concludes that “there was no central control of these [wage] payments…through the whole of this period.” The nature of this barter economy made it harder for the central government to monitor, assess, or regulate transactions across the kingdom. As a result, local autonomy was prevalent, and local officials often operated semi-independently from the pharaoh.

When positioned in the context of the Late Bronze Age Collapse, the primary issue of a decentralized economy is that it stripped nations of the capability to effectively combat frequently appearing risk factors. In the case of Mycenean Greece and New Kingdom Egypt, the health of their economies rested upon agricultural production. If agrarian production failed consistently, then there would be internal instability. The government would not be able to manage a complex trading relationship with other states when there was internal discord and a crisis that threatened the livelihoods of thousands. To secure agricultural production against climate change and invaders like the Sea Peoples required the presence of a strong economic authority that could use its power to directly alleviate these significant sources of risk and unpredictability for farmers. Thus, when there was no such strength in the authorities, these Mediterranean domestic economies were highly fragile to external blows, further jeopardizing their ability to maintain trade. This point partially explains the sudden collapse of trading activities during the 12th century B.C.E.

Inconsistent, Unstable Political Governance

If weak economic decentralization worked like HIV by allowing states to be more easily maimed by external strikes, then an uneven level of political governing competence across these states sowed the seeds for interstate conflicts and other risks to emerge.

Egypt was arguably the one with the greatest political might among all the cultures along the Mediterranean coast. Its political prowess stemmed from two factors. First, Egypt boasted the strongest sense of national unity. Since the Upper and Lower Egypt unification around 3150 B.C.E., Egypt maintained relative territorial integrity for most of its history until the end of the New Kingdom. This integrity translated into a standard, almost religious belief that Egypt must not be divided from within or by outsiders. During the late New Kingdom (from c. 1300-1250 B.C.E.), under the rule of competent pharaohs such as Ramses II, although political disruptions to stability occurred, they were not enough to upend the central political-cultural will for a unified Egypt. The desire for unity meant that Egypt developed a powerful central government that could organize effective schemes to strengthen national defense and crush internal dissent.

Second, from the perspective of geography, the Nile Valley, upon which the ancient Egyptians built their civilization, facilitated the maintenance of political centralization. The river provided a central “highway” for transportation and communication from north to south. The ease of transportation allowed for efficient administration and movement of troops. Towns, temples, and agricultural estates were concentrated along the river, making governance more manageable than regions with dispersed populations. Surrounded by deserts and the sea, the Valley was a further natural protective buffer against foreign invaders.

In contrast to the Egyptians, the Hittites, who were also primarily sedentary, suffered from a much weaker central political core. The Hittites ruled over a vast swathe of land in Asia Minor or Anatolia. The geography of this land proved to be a factor that prevented the Hittites from developing a strong, centralized, and stable state. Anatolia consisted of large areas of plain terrain, posing few natural barriers for invading tribes. The grand Halys River runs through the Hittite heartlands, thereby making the land highly lucrative to the nomadic peoples that surrounded the Hittite kingdom. These potentially hostile groups included rival principalities or kingdoms like “Arzawa” and “Kizzuwatna.” Lying beyond were the powerful and rivalrous Egyptian and Mitanni empires. Consequently, throughout its history, foreign forces constantly challenged the Hittites, who could not form an effective line of defense due to the confines of geography. Nor could they effectively expand their territories to claim buffer zones and forge a politically mighty empire. Creating a consistently unified political state was virtually impossible for Hittite kings and generals.

Aside from the Hittites, many other states around the Mediterranean similarly suffered from political instability and weak central authorities. For instance, though Cyprus served as a nexus of Late Bronze Age trade, it could, at best, be described as a collection of large towns and autonomous urban entities. As a result, the Cyprian government lacked the power to coordinate efforts to set up infrastructure and fortified walls for national defense. This incompetency made the state highly fragile to invasions from beyond.

When one takes in the internal political conditions of Mediterranean nation-states together, one shall understand why it would be challenging to forestall a final, sudden collapse. First, the de facto “weak” states like the Hittite kingdom and Cyprus could not consistently repel unexpected strikes from well-armed marauding forces like the Sea Peoples. In one text concerning the first wave of conflict between the Sea Peoples and the Bronze Age Mediterranean states, Merneptah, the Egyptian pharaoh at the time, sent many ships carrying grain for the “survival of Hatti.” The information that the Hittites needed food support from the Egyptians suggests that the former was in a critical situation during the invasion. Referring to the Sea Peoples, the pharaoh remarked: “Their chief is like a dog [...] bringing to an end the Pedetishew, whom I caused to take grain in ships, to keep alive that land of Kheta.” The term “Pedetishew” likely refers to an Anatolian region called Pitassa by the Hittites. From texts as such, this essay hence argues that the inability of the Hittites to achieve sustained national unity deprived them of their capabilities to fend off waves of sudden incursion.

Second, the disparity in political power between these Bronze Age states means that interstate conflicts always existed. Such conflicts threatened the stability of the already fragile trading network.The conflict between the Egyptians and Hittites over Syria is a prime example of how interstate power struggles disrupted fragile trading networks. The Hittites, the arguably weaker power in this relationship, sought control over Syria's resource-rich and strategically vital lands to gain a strategic advantage over the Egyptians and other powerful neighbors. The prolonged rivalry, culminating in the famous Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE), destabilized the region, as cities and trade hubs in Syria were often caught in the crossfire or forced into shifting allegiances. This competition hindered the free flow of goods and resources and prevented a consistently united effort to protect the trade network against disrupting climatic or human forces.

Conclusion

Overall, this essayist believes that while one can argue that climate disasters and the sudden raids of the Sea Peoples caused the Late Bronze Age Collapse, new perspectives like the ones proposed in this article – the frail internal economic and political conditions of states – should also be considered in light of all the relevant historical evidence. The issues of decentralized economies and unstable states planted the seeds of destruction. The incursions of the Sea Peoples and a sequence of droughts or other extreme weather events acted only as the final triggers.

The Late Bronze Age Collapse reveals crucial revelations for today’s globalized network. Debating about the decline phase that globalization is currently in is a waste of effort. Policymakers and citizens alike should be more concerned about an abrupt and precipitous fall like the eventual fate of the Mediterranean Bronze Age world. Just like how states then were plagued by economic and political ailments, many countries, even superpowers like the US, today are similarly beset by challenges brought by an unsustainable economy and chaotic politics. Who knows whether the seeds of destruction have already been planted into the current system? And therefore, who knows what will be the possible harbinger of globalization’s fall? A climate catastrophe? A series of unexpected wars? An AI infiltration? Or perhaps a combination of these calculated and uncalculated risks? While leaders convene to discuss how to strengthen the WTO, the IMF, the UN, and other global institutions designed to support the globalization framework, they should also devote more attention to the domestic conditions of their nations. If nations fail to function within, constructing and maintaining a complex international network would surely be a mere, impossible fantasy.

《青铜时代晚期地中海贸易网络的瓦解》

(地中海晚期贸易网络地图,来自于:https://www.worldhistory.org/image/15310/the-late-bronze-age-collapse-c-1200---1150-bce/)

简介

3200多年前,地中海是历史上第一个“全球化”网络的所在地,一个庞大的贸易体系将该地区的重要强国联系在一起:埃及、巴比伦、米诺斯、迈锡尼、赫梯等等。从地中海的沉船中发掘出的象牙雕刻饰品、黄金首饰与来自不同地区的昂贵的、被交易的原材料都可以追溯到这个时期。然而,从公元前1200年到公元前1150年这半个世纪左右的时间里,这个早期的全球化繁荣时期却突然神秘地结束了。到公元前1150年,考古学家未能找到令人信服的证据表明这些民族国家之间仍然存在系统的贸易。

青铜时代晚期的瓦解,也就是历史学家今天对这一事件的冠名,是历史上最引人入胜的例子之一,体现了历史不可预测的动力与不断变化的本质。历史学家至今仍在争论这一瓦解的诱因。一种流行的观点认为,一系列气候因素和一群掠夺性游牧民族--“海民”--的入侵突然对系统的平衡造成了致命打击。本文将对这一流行观点进行重新评估,并认为虽然这些外部“X因素”在一定程度上可能是必要的,但参与这一网络的民族国家内部存在的经济与政治问题应被视为导致其解体的更关键因素。

经济中央集权程度低且效率低下

由于青铜时代晚期的地中海网络依赖于持续不断的经济贸易作为其生命线,因此它的瓦解可能与相关经济状况的恶化密切相关。为了进一步深入研究这一点,我们可以考虑青铜时代晚期世界两大强国的经济结构:迈锡尼希腊(约公元前1750-1050年)与法老时代的新王国埃及(约公元前1550-1070年)。

迈锡尼时代的希腊政权位于希腊大陆与爱琴海周边的一些岛屿上,政府几乎没有对其农业经济进行集中控制的迹象。正如著名考古学家和专家保罗-哈尔斯泰德(Paul Halstead)所声称,“相当一部分农业主食......来自‘独立’耕作土地的生产者”。这句话表明,居住在宫殿中的迈锡尼国家中央统治者要么没有意愿,要么未能保持对其土地上重要农业生产的控制。

缺乏经济集权可归因于管理与降低风险的行政成本过高。迈锡尼人所面临的气候相当难以预测。例如,如果干旱来袭导致农作物歉收,当局必须在“财政上”补给小农户,或者为他们提供更多的生产要素(尤其是资本和劳动力),以大大提高生产率。然而,这两种解决方案都会导致行政成本上升,需要花费大量精力来评估并审议应实施的救济计划,特别是考虑到随机自然灾害的频繁发生。因此,掌权的官员逐渐发现,监督经济表现越来越具有挑战性,他们只能允许农业生产被分割成小块的,由经济中个人控制的单位。

同样,法老及其官员对埃及经济的掌控也很薄弱。斯坦福大学人文中心进行的一项有趣的研究跟踪了埃及劳动工资的分配情况:啤酒与面包。由于啤酒与面包是构成埃及经济基石的必需品,因此这些劳动工资的变化和分布可以高度反映当时埃及的经济状况。通过使用“体积标准化”方法,研究得出结论:“在整个时期,这些(工资)支付......没有中央控制”。这种易货经济的性质使得中央政府更难监控、评估或管理整个王国的交易。因此,地方自治盛行,地方官员的运作往往半独立于法老。

在青铜时代晚期瓦解的背景下,分散型经济的主要问题在于,它使国家失去了有效应对频繁出现的风险因素的能力。就迈锡尼时代的希腊与新王国时期的埃及而言,其经济的健康发展依赖于农业生产。如果农业生产持续失败,那么国内就会出现不稳定。当内部不和谐或危机威胁到成千上万人的生计时,政府将无法处理与其他国家的复杂贸易关系。要确保农业生产不受气候变化和海民等入侵者的影响,就必须有一个强大的经济权威机构,能够利用其权力直接减轻农民面临的这些重大风险及不可预测性。因此,如果当局没有这样的力量,这些地中海地区的国内经济就很容易受到外部打击,从而进一步削弱其维持贸易的能力。这一点部分解释了公元前12世纪贸易活动突然瓦解的原因。

不一致与不稳定的政治治理水平

如果说薄弱的经济分权就像艾滋病毒一样,使国家更容易受到外部打击的伤害,那么这些国家之间参差不齐的政治治理能力则为国家间冲突和其他风险的出现埋下了种子。

可以说,埃及是地中海沿岸所有文化中政治实力最强的国家,其实力源于两个因素。首先,埃及拥有最强烈的民族团结意识。自公元前3150年左右上埃及和下埃及统一以来,埃及在其历史的大部分时间里一直保持着相对完整的领土,直到新王国结束。这种完整转化为一种标准的、近乎宗教般的信仰,即埃及内部或外部不得分裂。在新王国晚期(约公元前1300-1250年),在拉美西斯二世等能干的法老的统治下,虽然出现了破坏稳定的政治动乱,但这些动乱并不足以动摇埃及统一的核心政治文化意志。对统一的渴望意味着埃及建立了一个强大的中央政府,能够组织有效的计划来加强国防并镇压内部异己。

其次,从地理角度来看,古埃及人赖以建立文明的尼罗河谷有利于维护政治中央集权。尼罗河为南北交通和通讯提供了一条中心“高速公路”。便利的交通使行政管理和军队调动更加高效。城镇、寺庙和农业庄园都集中在河流沿岸,与人口分散的地区相比,更便于管理。河谷被沙漠和大海环绕,是抵御外敌的天然缓冲地带。

与埃及人相比,同样以定居为主的赫梯人的中央政治核心要薄弱得多。赫梯人统治着小亚细亚或安纳托利亚的大片土地。事实证明,这片土地的地理位置是阻碍赫梯人建立强大、集中和稳定的国家的一个因素。安纳托利亚由大片平原组成,对入侵部落几乎没有天然屏障。宏伟的哈里斯河穿过赫梯人的中心地带,因此这片土地对赫梯王国周围的游牧民族来说非常有利可图。这些潜在的敌对群体包括敌对的公国或王国,如“阿尔扎瓦”和“基祖瓦特纳”,更远的土地上则是强大的埃及帝国与米坦尼帝国。因此,在青铜时代中期至晚期的历史中,外来势力不断向赫梯人发起挑战,而赫梯人由于地理位置的限制,无法形成有效的防线。他们也无法有效地扩张领土,建立缓冲地带,打造一个政治上强大的帝国。对于赫梯国王和将军来说,建立一个始终统一的政治国家几乎是不可能的。

除了赫梯人,地中海周边的许多其他国家也同样存在政治不稳定和中央政权薄弱的问题。例如,塞浦路斯虽然是青铜时代晚期的贸易枢纽,但充其量只能说是一个大城镇和自治城市实体的集合体。因此,塞浦路斯政府无力协调建立基础设施或防御工事,这种无能使国家在面对外敌入侵时非常脆弱。

当我们综合考虑地中海民族国家的内部政治条件时,就会明白为什么要防止最终的突然瓦解是一项挑战。首先,赫梯王国与塞浦路斯等事实上的“弱小”国家无法持续抵御像海民这样装备精良的掠夺势力的突然袭击。在一篇关于海民与青铜时代地中海诸国第一波冲突的记载中,当时的埃及法老默内普塔(Merneptah)派出了许多船只,为“赫梯的生存”运送粮食。赫梯人需要埃及人提供粮食支持的信息表明,在入侵期间,前者的处境十分危急。法老在提到海民时说:“他们的首领就像一条恶狗[......]终结了Pedetishew人,我让他们用船运送粮食,以维持Kheta那片土地的生命"。“Pedetishew "一词很可能是指赫梯人称之为Pitassa的安纳托利亚地区。因此,本文从这些文本出发,认为赫梯人无法实现持续的国家统一,从而丧失了抵御突然入侵的能力。

其次,青铜时代国家之间政治力量的悬殊意味着国家间的冲突始终存在,这些冲突威胁着本已脆弱的贸易网络的稳定。埃及人与赫梯人在叙利亚问题上的冲突就是国家间权力斗争如何破坏脆弱贸易网络的最好例子。在这种关系中,赫梯人可以说是实力较弱的一方,他们试图控制叙利亚资源丰富、战略地位重要的土地,以获得对埃及人和其他强大邻国的战略优势。这场旷日持久的竞争以著名的卡德什之战(约公元前1274年)为高潮,破坏了该地区的稳定,因为叙利亚的城市和贸易中心经常陷入战火,或被迫改变效忠对象。这种竞争阻碍了货物和资源的自由流通,也妨碍了人们始终团结一致保护贸易网络免受气候或人为因素的破坏。

结论

综上,本文作者认为,尽管人们可以认为气候灾害与海民的突然袭击导致了青铜时代晚期贸易网络的瓦解,但也应该根据所有相关的历史证据来考虑像本文提出的其他角度,即国家内部脆弱的经济与政治条件。毫无中央集权式的经济框架与不稳定的政治治理埋下了毁灭的种子。海民的入侵与一连串的干旱或其他极端天气事件只是最后的导火索。

青铜时代晚期的瓦解给当今全球化网络带来了重要启示。对全球化目前所处的衰落阶段进行争论是白费力气:政策制定者和公民都应该更加关注像地中海青铜时代世界最终命运那样的突然、急剧的衰落。就像当时的国家饱受经济与政治恶疾的困扰一样,今天的许多国家,甚至像美国这样的超级大国,也同样受到不可持续的经济与混乱的政治所带来的挑战的困扰。谁知道创造破坏的种子是否已经种进了当前的体系?因此,谁知道全球化衰落的先兆会是什么?气候灾难?一系列意想不到的战争?人工智能的渗透?又或者是这些已计算和未计算风险的组合?当各国领导人聚在一起讨论如何加强世贸组织、国际货币基金组织、联合国以及其他旨在支持全球化框架的全球机构时,他们也应更多地关注国内的状况。如果国家不能在内部发挥其功能,那么构建、维护一个复杂的国际网络肯定只会作为一个不可能实现的幻想而存在。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/652

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权