GEB 2/LBEW 33 - Strange Loops 2 集异壁2/东西方的连接33 - 怪圈2

Immanuel Kant’s essay “Idea of Universal History with Cosmopolitan Intent” illustrates the dual nature of humankind. On one hand, people are gregarious and social. They prefer to organize themselves by different groups, such as a state or religion. On the other hand, though, people have an innate unsociability. At times, one prefers to isolate themselves from a community or even demonstrate a clear antagonism towards it. This unsociability is the root cause of warfare and conflict in general, which destroy a previous system or society. However, wars and conflicts usually result in a the creation of a new organization as the sociability nature of people takes over again.

The last essay explains how this cycle, or “strange loop” describing the growth and decline of social organizations driven by the alternating sociable and unsociable human nature can be seen in the forms of government. This essay will pivot to the international economy and examine the strange loop within historical economic globalization. By examining the boom and bust of the Late Bronze Age international trade network and the Silk Road, this essay shall display the ebb and flow pattern of economic globalization.

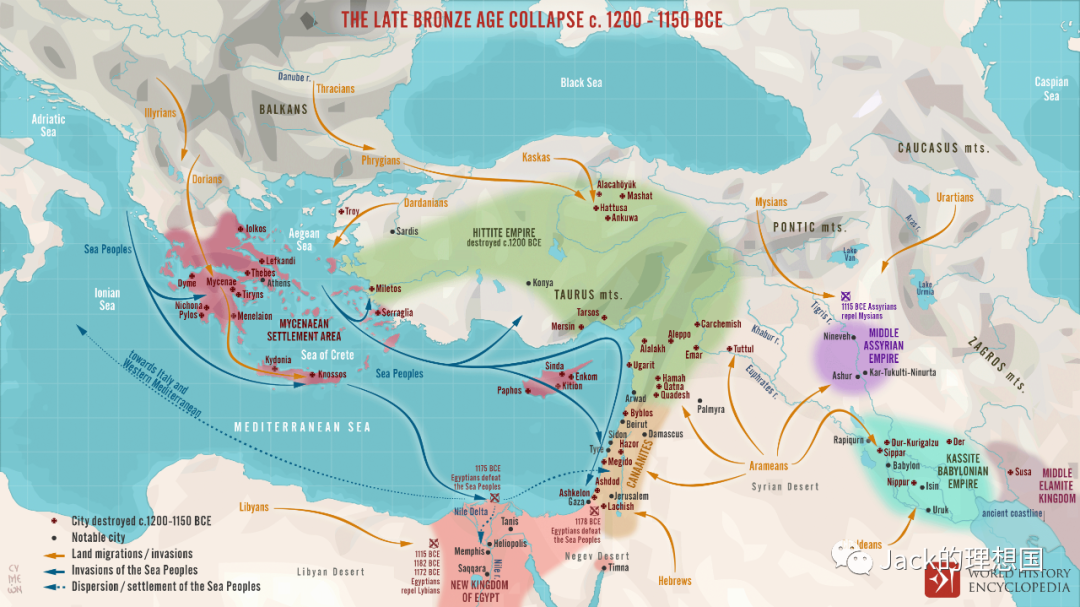

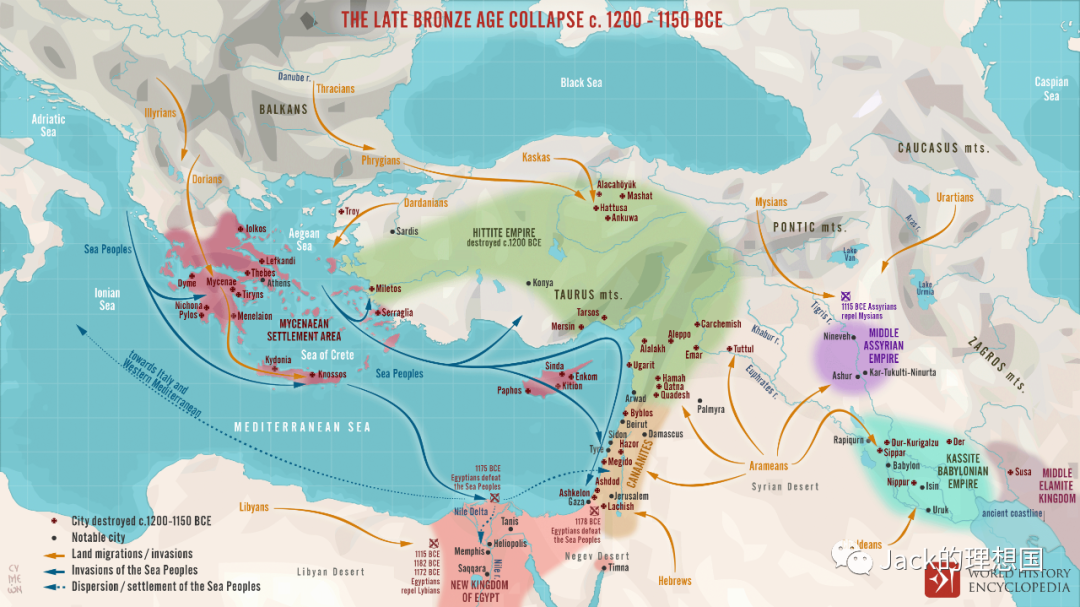

(A map illustrating the Late Bronze Age international trade network)

Start with the Late Bronze Age international trade network. The Bronze Age international trade network was one that intricately connected the Mediterranean world from the years 1500 to around 1250 BCE. It arose due to a greater international demand for some of the raw materials for the mass production of bronze and a growing willingness displayed by different cultures to build more complex bonds. Around 3000 BCE, ancient innovators began to smelt copper with tin to create the stronger bronze. As people gradually shifted from using copper to bronze, the demand for the latter metal alloy increased. An increase in the demand for bronze further pushed up the demand for tin and other raw materials. But materials like tin was not a common metal at that time, so cultures must choose to trade for it to eventually produce bronze at a larger scale. This mutual demand for rarer raw materials fostered a continuous multilateral trade network.

Another factor that catalyzed the formation of the Bronze Age network was a rising inevitability for cultures to establish more complex inter-relations. As the Bronze Age began, more advanced societies emerged. One such example would be the Mycenean Greeks. Compared to their predecessors, such as the Minoans, the Myceneans advanced towards more complicated forms of government. Their governmental institution resembled more of an aristocracy than a monarchy, and social stratification increased. The growing complexity of civilizations such as the Myceneans meant that societies would have the need and abilities to come into greater contact, and exchange products with each other on a greater scale. The sociable nature of humankind marked this period when Mediterranean cultures weaved an international economic network.

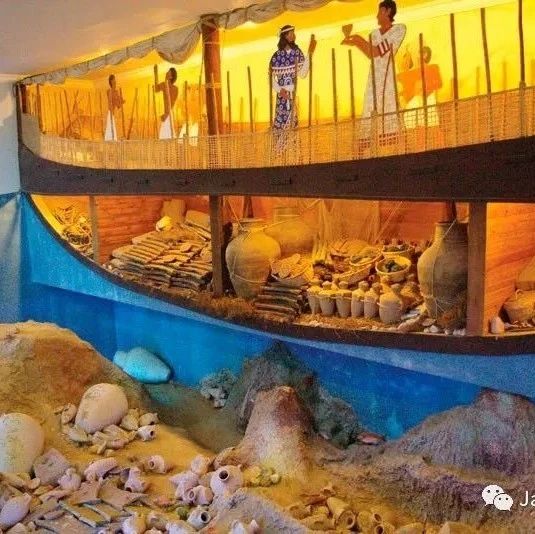

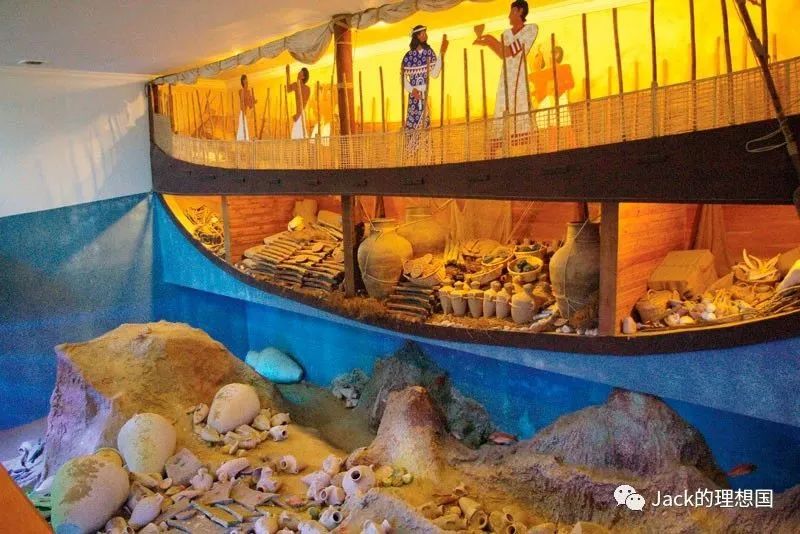

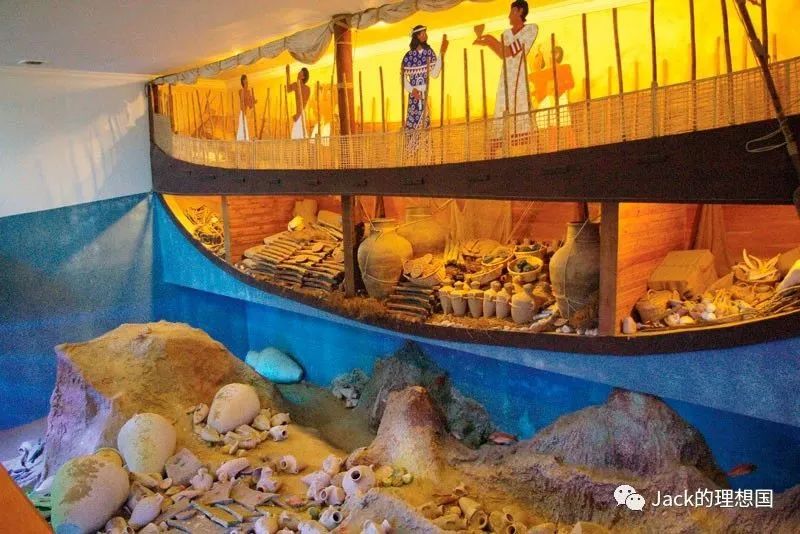

(The Uluburun Shipwreck)

At its zenith, the Bronze Age network connected about five different major cultures and a dozen of minor civilizations that dotted the coasts of the Mediterranean. One piece of historical evidence to demonstrate the width of this network is the Uluburun Shipwreck. The Uluburun Shipwreck dated to the late 14th century BCE. Underwater archaeologists discovered the Shipwreck near modern-day Turkey in the Mediterranean Sea in 1982. The ship possibly set sail from a Cypriot port, and its destination, after much deliberation among historians, was probably one of the Mycenean palaces in mainland Greece. The vessel contained goods and materials from around nine or ten civilizations, from northern Europe to Africa, and as far west as Sicily, as far east as Mesopotamia. Some of its goods included ivory from Syria, copper and tin ingots from Cyprus, Canaanite jars from Egypt, and four swords produced most likely by the Myceneans. The Uluburun Shipwreck shows that during the late stages of the Bronze Age, the Mediterranean world was the nexus for trading activities across an extended region. Aside from its geographical position, the Mediterranean could uphold such an extensive trade network because its participants all had a sustained need and will to establish links with each other.

However, around 1170 BCE, this system of economic trade and communication began to rapidly collapse. Historians still debate the reasons for this collapse. This essay likes to present the occurrence of this event as the product of several economic and historical trends.

First, by around 1200 BCE, it was clear that a new form of metallurgy known as ironworking formed a trend and began to spread across Eurasia, including the Mediterranean region. Ironworking significantly disrupted the workings of the bronze economy. As people realized that iron is far more durable and easier to produce than bronze, the demand for bronze fell quickly. As the demand for bronze decreased drastically, the Mediterranean network that, for its most part, relied on bronze gradually disintegrated.

Second, the 50-year period from 1200 to 1150 BCE witnessed the widespread invasions by a mysterious group of people known as the Sea Peoples. The Sea Peoples, historians hypothesized, was a seafaring confederation that maimed the Egyptians, Mycenean Greeks, and other regions in the East Mediterranean. For instance, the city of Karaoglan, near modern-day Ankara, was burned. Other cities in Egypt and Cyprus suffered similar fates. Due to their usage of iron weapons and the general decline of multiple cultures, the Sea Peoples could deliver considerable damage to these Mediterranean civilizations, effectively breaking the networks that connected them.

Third, natural calamities constituted a factor that accelerated the demise of the Mediterranean trade network. Archaeological evidence from Turkey reveals that there were prolong periods of draught during the 12th century BCE. These periods of draught resulted in decreases in population and the production of economic goods. When most economies at that time ceased to produce goods in immense numbers, the trade system collapsed naturally.

Another case of a boom-and-bust cycle of international trade is the Silk Road. The Silk Road was an economic route that connected China with states and empires to the west, namely the Romans, from around 200 BCE to 1453 CE. But the Silk Road also included trade routes with Persia, India, and even the Korean Peninsula.

Like the Mediterranean trade network, the Silk Road formed due to a marked increase in the demand for certain goods. For the Han Dynasty around 200 BCE, strong horses were of great demand, since the military needed them to combat the nomadic tribes to the northwest and extend the Han Empire’s territories. Under the order of the Emperor Han Wudi, the Han explorer Zhang Qian sought to open a trade route to the west for the Han Empire to trade for such horses with the smaller kingdoms beyond the border. After the Han army secured this shorter trade route, explorers and traders began to look further to the west to satisfy the Chinese’s demand for more exotic items. By around the second century BCE, trade networks with India, Persia, and Rome emerged, laying the foundation for the Silk Road to blossom.

Moreover, the Silk Road’s formation can be attributed to the growth of power for the Han Empire and the Roman Republic, which made their contact with each other inevitable. The Han Empire, under Emperor Han Wudi, was rapidly expanding its territories to the west, and its sphere of influence was spreading to Persia or even beyond. The Roman Republic, too, successfully expanded its territories as the Silk Road opened. Under a series of powerful military blows and diplomacy, the Romans were in firm control of large swathes of Europe in the 100s BCE. Its sphere of influence further spread to North Africa after the conquering of Carthage in 146 BCE. This era of massive expansion for both powers meant that their spheres of influence intersected in areas like Persia and the Middle East. These intersections culminated in the establishment of the Silk Road.

(An illustration of both the land and maritime routes of the Silk Road)

The Silk Road reached its most flourishing state from around the seventh century CE to the early 14th century. During this period of great flourishing, goods including glass, porcelain, silk, and all kinds of spices flowed between the Chinese and the Romans and the kingdoms in Persia or India. The Tang Dynasty grew rapidly during the 600s, conquering vast amounts of territory that belonged to the nomadic tribes to the west, further securing the flow of immense amounts of goods. The Byzantine Roman Empire, in this same period, was establishing firmer links with the Persians and sending envoys to China. Primary sources such as the New Book of Tang contain records of alleged embassies by Byzantine emperor Constans II to the court of Emperor Taizong of Tang. The Tang Chinese also welcomed foreign cultures, making it quite cosmopolitan and culturally diverse in its urban areas. Thanks to a stronger maritime presence in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and at the Horn of Africa, Chinese merchants developed the maritime Silk Road too. The maritime Silk Road, at the height of its prosperity, linked modern-day Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Combining the maritime and land routes together, the Silk Road from the 600s to the 1300s was arguably the most complicated and effective trade network established in history by that point.

Unfortunately, the Silk Road, like the Bronze Age network, collapsed at a fast pace in the 1400s due to a variety of complex factors. By the 14th century, the demand for Chinese silk in the west was falling. Historical records show that during the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Empire managed to obtain silkworm eggs and could being silkworm cultivation independently. The spread of sericulture meant that Chinese silk exports became less important, hence trade for this item diminished. In the 14th century, the Mongol Empire’s reign ended abruptly, loosening the political, cultural, and economic unity of the Silk Road as a power vacuum appeared. Many of the smaller Persian states either fell victim to the extended effects of the Black Death or to internal disintegration. At the same time, the Ottoman Empire, armed with the more powerful gunpowder, began to seize land around the western part of the Silk Road from the decaying Byzantine Empire. In 1453, the Ottomans conquered Constantinople, gaining control over a significant center on the Silk Road. The Ottomans boycotted the trading activities with China or its neighboring states, marking a final decline of the Silk Road.

The cases of the Bronze Age international network and the Silk Road delineate an intriguing boom-and-bust cycle of economic globalization. In both cases, the trading activities grew into far-reaching networks that connected civilizations from different continents, yet these networks eventually had to face their respective demise over a few centuries. The patterns one can decipher from these boom-and-bust cycles provide some clues for the direction of globalization today. Since the beginning of the pandemic, economic globalization has most likely been in retreat. In 2022, several vital economies, including the US, displayed a protectionist attitude regarding the world economy. The question is, in the near term, will this current globalized system collapse too, like how the Bronze Age network and the Silk Road did?

This essay takes a more optimistic stance. From the cases of the Bronze Age network and the Silk Road, one can generalize precursive events that led to the fall of international economic networks. One precursive event is the sudden appearance of a more dominating force that was previously not a participant in the economic network. For the Bronze Age Mediterranean world, that dominating force was the Sea Peoples. For the Silk Road, that dominating force was the Ottomans. This kind of event is a significant factor as this force usually possesses the ability to disrupt the workings of the system or even destroy it. In the current world, there is no such sign of an event happening. In fact, the status quo is more likely to fall victim to internal discord than an external threat.

Another precursive event is the fall in demand for the vital goods being traded in the system. By 1200 BCE, iron proved a better substitute for bronze, causing the demand for bronze and the raw materials to make bronze to drop exponentially. This loss of demand took away the motives for trade, effectively ending the system. By the 14th and 15th century CE, China lost its position as a monopoly in the silk industry as other cultures on the Silk Road gained their method of production. As a result, the demand for Chinese silk, a defining item being traded on the Silk Road, fell significantly. The Silk Road consequently lost most of its economic value. Currently, the demand for the vital goods, such as refined petroleum, automobiles, gold, and all sorts of consumer goods is still robust. In this sense, today’s economic globalization still possesses many incentives to proceed.

Finally, it is worth thinking about some of the most basic ideas that have underpinned every economic network. One of the ideas is the power of money. As Yuval Noah Harari wrote in his book Sapiens, “money is the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised.” Economic systems from the past to the present have been formed based on some type of money, be it cowry shells, gold coins, or the US dollar. When people collectively have trust in a type of money, they essentially endow that money with a fictional value that makes it accepted by the populace. Thus, as long as people have faith and trust for the concept of money, then any economic system would possess a fundamental driving force. This logic summarizes the reasons to be confident that the current economic system can bounce back.

WORKS CITED

Barasso, Michele. “What Caused the Bronze Age Collapse?” Biblical Archaeology Society, 29 June 2022, www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-near-eastern-world/what-caused-the-bronze-age-collapse/.

“Money & Politics.” Yuval Noah Harari, 15 Jan. 2020, www.ynharari.com/topic/money-and-politics/.

“Silk Road | Facts, History, & Map | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2023, www.britannica.com/topic/Silk-Road-trade-route.

康德在其论文《世界公民观点之下的普遍历史观念》之中论述了人类的双面性。一方面,人类是合群的并具有社会性的,喜欢将自己以各类形态链接,如国家或宗教。但另一方面,人们又有一种天生的不合群性与非社会性。有时,人们更愿意把自己从一个群体中孤立出来,甚至对这个群体表现出明显的对立情绪。这种不合群是战争和冲突的根本原因。一般来说,战争和冲突会破坏以前的制度或社会。然而,战争和冲突通常会导致一种新的组织方式的诞生,因为人们将重回他们的社会性本质。

上篇文章中,这种描述由充满社会性和非社会性的人性所驱动的社会组织的增长和衰退循环或 "怪圈 "被利用以分析政治系统的变化规律。这篇文章将转向世界经济,在历史上的经济全球化中试图看到这样的“怪圈”。通过研究青铜时代晚期国际贸易网络、丝绸之路和COVID时代的世界贸易的繁荣和衰落,本文将展示经济全球化的繁荣与萧条周期。

(青铜时代晚期的贸易网络地图)

从青铜时代晚期的国际贸易网络开始,这个国际贸易网络是一个错综复杂地连接地中海世界的网络,从公元前1500年到1250年左右。它的出现可归因于国际上对大规模生产青铜器的一些原材料有了更大的需求,且不同的文化也越来越愿意建立更复杂的联系。大约在公元前3000年,古代的创新者开始用锡来冶炼铜,以创造更强大的青铜。随着人们逐渐从使用铜转向使用青铜,对后一种金属合金的需求增加。对青铜需求的增加进一步推高了对锡和其他原材料的需求。但是像锡这样的材料在当时并不是一种常见的金属,所以各地文化必须选择用交易来换取它,以最终大规模地生产青铜。这种对稀有原材料的相互需求促进了一个持续的多边贸易网络。

催化青铜时代网络形成的另一个原因是文化复杂性的增长使文化间的交流成为必然。随着青铜时代的开始,更先进的社会出现了。迈锡尼希腊人就是这样一个例子。与他们的前辈,如米诺斯人相比,迈锡尼人向更复杂的政府形式发展。他们的政府机构更像一个贵族制,而不是君主制,社会分层也愈发加剧。像迈锡尼这样的文明的日益复杂化意味着各社会有必要也有能力进行更多的接触,并在更大范围内相互交换产品。人类的社会性是这一时期的标志,地中海文化能够编织一个国际经济网络。

(Uluburun沉船示意图)

在其顶峰时期,青铜时代的网络连接了遍布地中海沿岸的大约五个不同的大型文化和文明与数十种小文明。证明这个网络宽度的一个历史证据是Uluburun沉船。Uluburun沉船的年代可追溯至公元前14世纪末。水下考古学家于1982年在现代土耳其附近的地中海底发现了这艘沉船。这艘船可能是从塞浦路斯的一个港口起航,而它的目的地,经过历史学家的反复推敲,可能是希腊大陆的迈锡尼宫殿之一。这艘船载有来自大约九种或十种文明的货物和材料,从北欧到非洲,最西边到西西里,最东边到美索不达米亚。其中一些货物包括来自叙利亚的象牙,来自塞浦路斯的铜和锡锭,来自埃及的迦南人罐子,以及很可能由迈锡尼人生产的四把青铜剑。Uluburun沉船表明,在青铜时代的后期,地中海世界是整个扩展区域贸易活动的中心。除了它的地理位置外,地中海能维持如此广泛的贸易网络,更是因为其参与者都有持续的需求和意愿来建立彼此的联系。

然而,在公元前1170年左右,这种经济贸易和通信系统开始迅速崩溃。历史学家仍在争论这一崩溃的原因。这篇文章将把这一事件的发生归结为几种经济发展和历史趋势的产物。

首先,到了公元前1200年左右,铁器加工,作为新的冶金形式形成了一种趋势,并开始在欧亚大陆,包括地中海地区传播。铁器加工大大扰乱了青铜经济的运作。当人们意识到铁比青铜更耐用、更容易生产时,对青铜的需求迅速下降,导致大部分依赖青铜器的地中海网络逐渐瓦解。

其次,在公元前1200年至1150年间,一个被称为 "海族人 "的神秘群体进行了广泛的入侵。历史学家假设,海族人是一个航海联盟,他们残害了埃及人、迈锡尼希腊人和东地中海其他地区的文明。例如,现代安卡拉附近的卡劳格兰城被烧毁,埃及和塞浦路斯的其他城市也遭受了类似的命运。由于他们使用铁制武器且多种其他文化已呈现普遍衰落的形态,海族人可以给这些地中海文明带来相当大的破坏,有效地打破连接它们的网络。

第三,自然灾害构成了加速地中海贸易网络消亡的一个因素。来自土耳其的考古证据显示,在公元前12世纪,这一地区出现了长期的旱灾。这些旱灾导致了人口和经济产品生产的减少。当当时的大多数经济体不再大量生产商品时,贸易体系就自然崩溃了。

国际贸易繁荣与萧条循环的另一个案例是丝绸之路。丝绸之路是一条经济路线,从公元前200年左右到公元1453年,将中国与西方的国家和帝国,即罗马人连接起来。但丝绸之路还包括与波斯、印度,甚至朝鲜半岛的贸易路线。

与地中海贸易网络一样,丝绸之路的形成是由于对某些商品需求的明显增加。对于公元前200年左右的汉朝来说,对强壮的马匹有很大的需求,因为军队需要它们来打击西北的游牧部落,扩大汉帝国的领土。在汉武帝的命令下,汉朝探险家张骞为汉帝国开辟了一条通往西方的贸易路线,以便与边境以外的小国交换这种马匹。在汉军确保这条较短的贸易路线的安全性后,探险家和商人开始进一步向西寻找,以满足中国人对更多异国物品的需求。到公元前二世纪左右,与印度、波斯和罗马的贸易网络出现,为丝绸之路的开花结果奠定了基础。

此外,丝绸之路的形成可以归功于汉帝国和罗马共和国的实力增长,这使得他们之间的接触不可避免。汉武帝时期的汉帝国正在迅速向西扩张领土,其势力范围正在向波斯甚至更远的地方扩展。随着丝绸之路的开通,罗马共和国也成功地扩大了其领土。在一系列强有力的军事打击和外交手段下,罗马人在公元前100年就牢牢控制了欧洲的大片土地。公元前146年征服迦太基后,其势力范围进一步扩展到北非。这两个大国的大规模扩张时代意味着它们的势力范围在波斯和中东等地区相互交错。这些交叉点最终导致了丝绸之路的建立。

(陆地与海上丝绸之路)

丝绸之路从公元七世纪左右到十四世纪初达到最繁荣的状态。在这个大繁荣时期,包括玻璃、瓷器、丝绸和各种香料在内的货物在中国人和罗马人以及波斯或印度的王国之间流动。唐朝在600年代迅速发展,征服了属于西部游牧部落的大量领土,进一步保证了大量货物的流通。在同一时期,拜占庭罗马帝国与波斯人建立了更牢固的联系,并向中国派遣了使节(宋代的资料包含了据称是拜占庭皇帝康斯坦丁二世向唐太宗宫廷派遣使节的记录)。唐朝的中国人也欢迎外国文化,其城市地区具有相当大的世界性和文化多样性。由于在波斯湾、红海和非洲之角有较强的海上力量,中国商人也发展了海上丝绸之路。海上丝绸之路在其最繁荣的时候,将现代的伊拉克、沙特阿拉伯、埃塞俄比亚和索马里连接起来。将海上和陆地路线结合在一起,从600年代到1300年代的丝绸之路可以说是到那时为止历史上建立的最复杂和最有效的贸易网络。

不幸的是,由于各种复杂的因素,丝绸之路和青铜时代的网络一样,在14世纪快速崩溃。到了14世纪,西方对中国丝绸的需求正在下降。历史记录显示,在中世纪,拜占庭帝国成功地获得了蚕卵,并能独立地进行蚕的养植。养蚕业的普及意味着中国的丝绸出口变得不那么重要了,因此这种物品的贸易减少了。14世纪,蒙古帝国的统治戛然而止,随着权力真空的出现,丝绸之路的政治、文化和经济统一也随之松动。许多较小的波斯国家要么成为黑死病扩大影响的受害者,要么成为内部瓦解的受害者。同时,奥斯曼帝国以更强大的火药为武器,开始从衰败的拜占庭帝国手中夺取丝绸之路西部一带的土地。1453年,奥斯曼人征服了君士坦丁堡,获得了对丝绸之路上一个重要中心的控制。奥斯曼人抵制了与中国或其邻国的贸易活动,标志着丝绸之路的最终衰落。

青铜时代的国际网络和丝绸之路的案例勾勒出经济全球化的一个耐人寻味的繁荣和萧条周期。在这两个案例中,贸易活动成长为影响深远的网络,将不同大陆的文明联系起来,但这些网络最终不得不在几个世纪内面临各自的消亡。人们可以从这些繁荣和萧条周期中解读出的模式为今天的全球化方向提供了一些线索。自新冠疫情开始以来,经济全球化很可能一直在退缩。2022年,包括美国在内的几个重要经济体对世界经济表现出保护主义的态度。问题是,在短期内,目前这个全球化系统是否也会像青铜时代的网络和丝绸之路那样崩溃?

这篇文章采取更乐观的立场。从青铜时代网络和丝绸之路的案例中,我们可以归纳出导致国际经济网络崩溃的先导性事件。一个先导性事件是一个更有统治力力量的出现,而这个力量之前并不是经济网络的参与者。对于青铜时代的地中海世界来说,这个主导力量是海族人。对于丝绸之路来说,这个主导力量是奥斯曼人。这种事件是一个重要的因素,因为这种力量通常拥有扰乱系统运作的能力,甚至摧毁它。在目前的世界上,没有这种事件发生的迹象。事实上,现状更有可能成为内部不和的受害者,而不是外部威胁。

另一个先兆事件是对该系统中正在交易的重要商品的需求下降。到公元前1200年,铁被证明是青铜的更好替代品,导致对青铜和制造青铜的原材料的需求成倍下降。这种需求的丧失使贸易的动机消失,有效地结束了这个系统。到了公元14和15世纪,由于丝绸之路上的其他文化获得了他们的生产方法,中国失去了其在丝绸行业的垄断地位。因此,对中国丝绸的需求大幅下降,而中国丝绸是丝绸之路上交易的一个重要项目。丝绸之路也因此失去了大部分的经济价值。目前,对精炼石油、汽车、黄金和各种消费品等重要商品的需求仍然强劲。从这个意义上说,今天的经济全球化仍然拥有许多进行的动力。

最后,值得思考的是一些最基本的想法,这些想法支撑着每一个经济网络。其中一个想法就是金钱的力量。正如尤瓦尔-诺亚-哈拉里在他的《人类简史》一书中写道,"金钱是有史以来最普遍、最有效的互信系统"。从过去到现在的经济体系都是在某种类型的货币基础上形成的,无论是贝壳,金币,还是美元。当人们集体信任某种类型的货币时,他们基本上赋予这种货币以虚构的价值,使其被民众接受。因此,只要人们对货币的概念有信心和信任,那么任何经济体系都会拥有一个基本的驱动力。这一逻辑总结了相信当前经济体系能够反弹的理由。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/603

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权