Links Between East and West 38 History Recording 东西方的连接38 - 历史记录

The recording of history was born from the innate desire of humankind to take note of the past. 70,000 years ago, after the Cognitive Revolution, when humans fulfilled the needs of survival, including food and shelter, they had the time and attention to harness their language and creativity to document the past. While it might be true that the primary cultures scattered across the world had some form of historical recording, the existence of such forms has been difficult to prove and analyze. Systematic historical recording only began with the emergence of organized societies and the invention of a writing system. This essay will examine the oracle bones of Shang China, Si Ma Qian’s work The Historical Records, and Roman historian Livy’s writings to demonstrate the universal nature of historical writing.

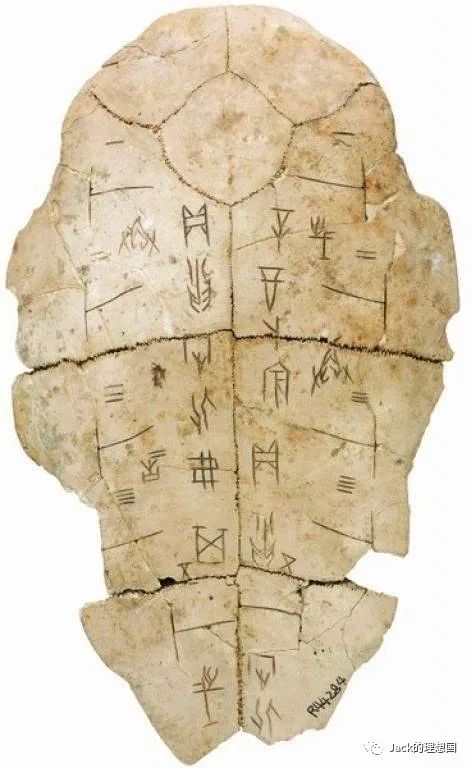

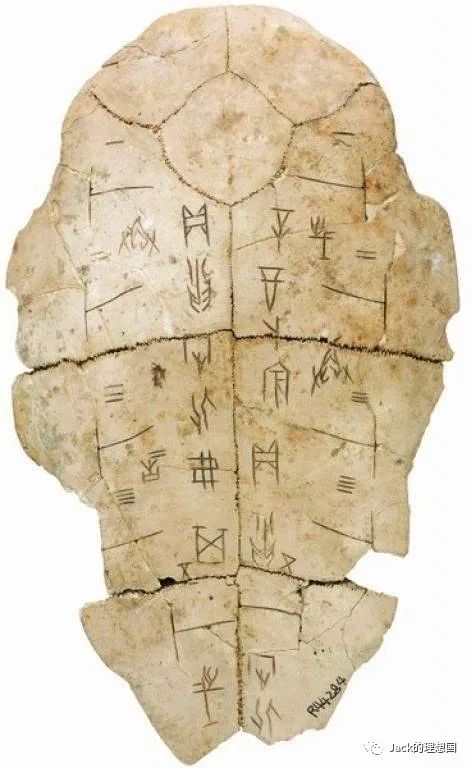

China’s culture has greatly emphasized the recording of the past. The essence of its culture is composed of the reverence for history on different levels. On the family level, in traditional Chinese culture, it is customary to keep a family tree and pay tribute to the ancestors regularly. On the state level, Chinese governments, in most dynasties, set up government positions for historians. Emperors viewed the recording of the past as an indispensable and honorary act. In China, history almost becomes a powerful religion that unites all citizens. Historical recording first became systematic more than 3000 years ago during the Shang Dynasty. Some excavated oracle bones contain evidence of such activities. For example, one oracle bone documented the life and accomplishments of one of the first kings of the Shang Dynasty, who helped establish the basis of the empire. Other oracle bones documented past prayers and the results from these prayers. Although one can argue that the oracle bone inscriptions do not belong to the scientific tradition of history as a subject (since many are in the form of religious prayers), but as Hegel claimed, historical recording usually begins with the foundation of the state. Thus, the intrinsic criteria for determining historiography should be the presence of a writing system and a robust functioning state. The messages on the bones and the environment in which the bones were created fulfill both criteria, justifying the oracle bones as a primary form of historical recording.

In later eras, historical recording would gradually evolve to become one of the central tasks of Chinese scholars and even government officials. During the Han Dynasty, after prolonged warfare during the Spring and Autumn Period, China entered a time of restoration and cultural development. As the government gradually shifted the focus from preparing warfare to encouraging cultural creations, historiography advanced substantially as well. During this time, Sima Qian, one of the most respected historical Chinese scholars, started composing his tome, The Historical Records. The Historical Records can be divided into sections, each covering a certain period of Chinese history or an aspect of Chinese traditional culture. The content is about the achievements of past emperors, the rise and fall of different kingdoms, the specific records of construction, finance, etc. Sima Qian can be regarded as one of China’s earliest historians who systematically attempted to create a “database” for Chinese history.

The Historical Records was a revolutionary piece of writing at the time. Its impacts have been long-lasting. It set the tradition of official historical recording in China. Some contemporary Chinese scholars even claim it established a humanist belief in the culture. Previous to Sima Qian, historical recording was more sporadic and undertaken by various social groups. After Sima Qian, historical recording became more centralized and gained greater attention from the imperial courts. The Historical Records also created standards for scholars when conducting historical research or writing. The first standard regarded the scope of historical recording. From the Han Dynasty onwards, Chinese historical writing focused on the deeds of emperors and accomplished individuals and the specific occurrence of significant events. The second standard regarded the rigor of historical recording. Chinese historians began to adopt a more rigorous and scientific approach to history, aiming to be as factual as possible and check their work against previous recordings. Finally, The Historical Records marked the advent of a new method of historiography that combined the knowledge of political science, economics, and other related fields to weave a single complex narrative. This method was championed by Chinese scholars arguably until the introduction of modern Western historiography in the early twentieth century.

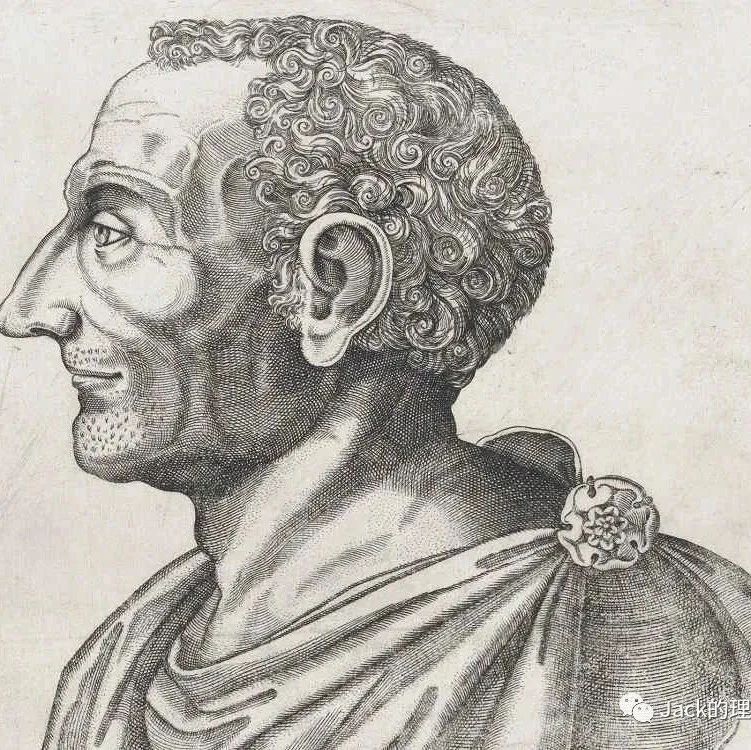

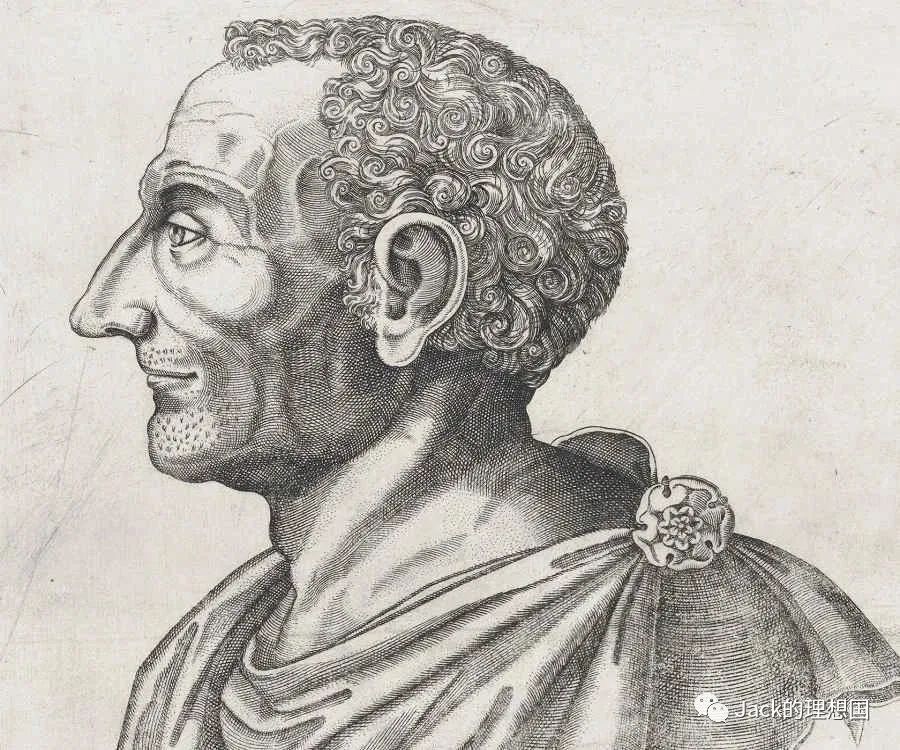

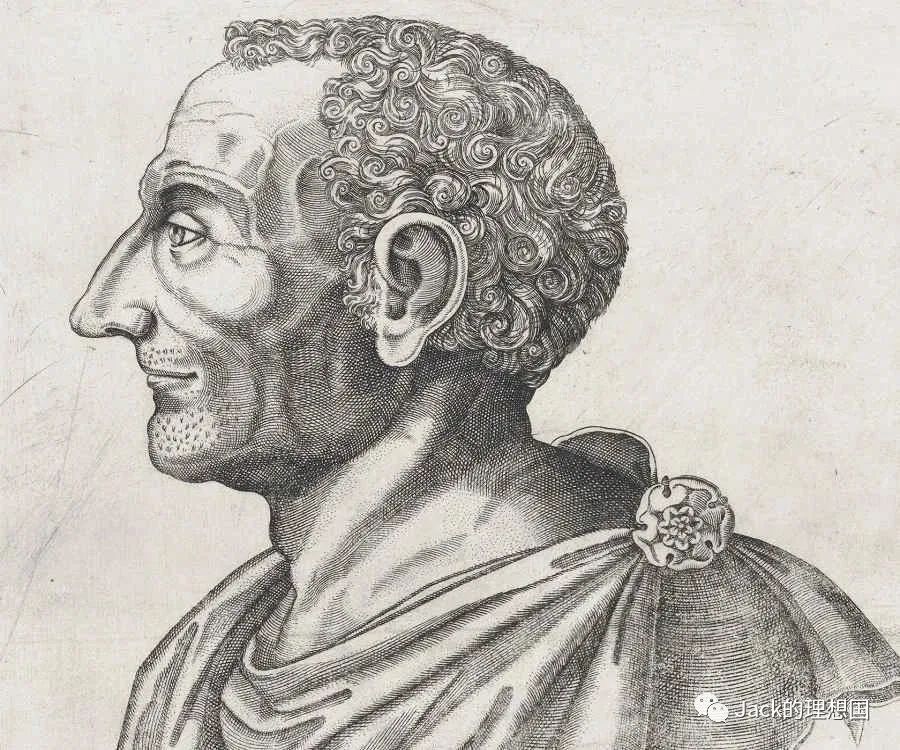

At the same time as Sima Qian, the Western hemisphere also witnessed the rise of prominent historians. The Mediterranean world had a rich convention of recording history. More than 2500 years ago, the ancient Greeks systematically recorded and studied past events. Figures such as Herodotus and Thucydides are just two examples. The Romans, having inherited the culture from the Greeks, pushed the development of historiography further. An outstanding historian at that time was Livy (59 BCE to 17 CE), known for his exhaustive research and documentation of Roman history. While he was unique among Roman historians in that he did not participate in politics or religious activities, he saw history in “personal and moral terms,” meaning that he interpreted the past more sensually or philosophically. Livy was one of the first historians to see history regarding significant individuals and personalities rather than political clashes.

Livy’s works left profound marks on Western historiography. First, he reshaped the style of historical writing to be more accessible to a greater audience. He made history more vivid and hence resonating and significant. One evidence of this attempt to reshape historiographical writing would be an increase in the variety of syntax in Livy’s works. At some moments, he would utilize long, periodic clauses to depict a scene in detail; at other times, he would switch to short and abrupt sentences to delineate the rapidity of action. Another piece of evidence would be his diction. Previously, historiography involved dry and formal use of words. Livy overthrew this convention and employed a wide range of lyrical or dramatic vocabulary. Such major changes in the writing style impressed many of his audiences, who were deeply drawn to the eloquence and vividness of his narrations. From Livy onwards, history would not be a subject only suited for the rich and powerful but rather one that anyone could approach with a scholarly mind.

Second, Livy’s focus on the moral and personal aspects of history significantly influenced future historians and the scope of Western historiography. Livy felt the decline of morality during his time with peculiar intensity, noting, “Where would you find nowadays in a single individual that modesty, fairness and nobility of mind which in those days belonged to a whole people?” The responsibility of historical recording should be to offer examples and warnings to an individual and their country. As a result, Livy tried to shift history from a purely political study to a subject that concentrated on human nature and the intrinsic interactions between individuals in social settings. Historians should be more interested in the individual human and the underlying patterns of societal progression. Livy inspired historians such as St. Augustine and even Enlightenment thinkers such as Immanuel Kant or Friedrich Hegel to take a similar path. For instance, Hegel devoted a large share of his focus to “world-historical individuals” and aimed to explain, in detail, the factors pushing social development through time.

Overall, by examining the oracle bones of Shang China, the Han historian Sima Qian, and the Roman historian Livy, historical recording appeared to be a vital activity for civilizations throughout different periods. When one dives deeper into the motives of historical recording, the question is: What is the role and value of history? As Nietzsche claimed, history serves life in various ways. For some, history provides courage. “The great which once existed was at least possible once and may well again be possible sometime.” With this knowledge, ambitious individuals can act with greater audacity and determination. For others, history provides a sense of belonging. Finding belonging in history is especially a tradition in China. Each individual has an intimate relationship with their family, city, and national history. When history can breathe life into the individual, then historiography is the natural process in which people attempt to find this powerful source of vitality.

In the modern context, while one must acknowledge the importance of history, it is also essential to be critical of history. As history breathes life into an individual, it can silently bind its tentacles around that individual and “strangle” them. History often preserves life but fails to generate it. People can readily use history to satisfy their desires to connect with memories yet would eventually find it difficult to innovate or break historical conventions. As this process unfolds itself, humankind can very well decay and degenerate. People must bring up new inspirations and ideas to navigate increasingly complex societies. With the constant advancement of groundbreaking technologies, the unspoken rules of social interactions are changing simultaneously. To keep up with such a hectic pace of development, people must have the strength to shatter and dissolve past elements, to condemn historical segments that discourage creativity. This “unhistorical” way of living might become more crucial as time passes. I am not arguing that historical recording should be abolished entirely in the future. Instead, it genuinely seems important to take advantage of history while always being aware of its potential dangers.

WORKS CITED

Nylan, Michael. “SIMA QIAN: A TRUE HISTORIAN?” Early China, vol. 23/24, 1998, pp. 203–46. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23354187. Accessed 2 July 2023.

Steele, R. B. “Livy.” The Sewanee Review, vol. 15, no. 4, 1907, pp. 429–47. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27530872. Accessed 2 July 2023.

对历史的记录诞生于人类与生俱来的试图链接过去的愿望。七万年前认知革命后,人类满足了生存的需要,包括食物和住所,他们有时间和注意力去利用他们复杂的语言系统及创造力以进行历史记录。虽然分散在世界各地的初级文化可能确实有某种形式的历史记录,但这种形式的存在一直难以证明和分析。系统的历史记录只是随着有组织的社会、国家的出现和文字系统的发明而开始的。本文将研究中国商代的甲骨文、司马迁的《史记》与罗马史学家李维的历史作品,以证明历史记录的普遍性。

中国的文化非常重视对历史的记录。其文化的本质是由不同层次中对历史的敬畏构成。在家庭层面上,中国传统文化中,人们习惯于保留家谱并定期祭祖。在国家层面,中国的政府,在大多数朝代,都为历史学家设置了政府职位。皇帝们将记录历史视为一种不可或缺的,展示统治能力的行为。在中国,历史几乎成为一种强大的宗教,将所有公民团结起来。在3000多年前的商代,历史记录首次变得系统化。一些出土的甲骨文含有这种记录的证据。例如,一些甲骨文记录了商朝初代国王的生活与成就,以及他们如何建立了帝国的基础。其他甲骨文记录了过去对神明的祈祷与祈祷的结果。尽管人们可以认为甲骨文不符合历史这一学科的科学传统(因为许多是以宗教祈祷的形式写成),但正如黑格尔所称,一般情况下,历史记录通常从国家的建立开始。因此,鉴定历史记录存在性的标准应是是否存在一个完整的书写系统和一个强大的运作国家。甲骨文上的信息和其书写的环境符合这两个标准,证明了甲骨文是历史记录的主要形式之一。

在后来的朝代,历史记录将逐渐发展成为中国学者与政府官员的核心任务之一。在汉代,经过春秋战国及秦朝时期的长期战乱与不稳定,中国进入了一段以政治重建和文化和平发展为首要目标的时期。随着政府逐渐将重点从准备战争转向鼓励文化创作,历史记录也有了较大的发展。正是在这一时期,最受尊敬的中国历史学者之一司马迁开始编写他的巨著《史记》。《史记》被分为诸多部分,每部分涵盖中国历史的某时期或中国传统文化的某方面,内容涉及历代帝王的功绩,不同王国的兴衰,建筑、财政等方面的具体数据记录。司马迁可以说是中国最早的历史学家之一,他试图系统地建立一个中国历史的 "数据库"。

《史记》在当时是一部革命性的著作,它的影响是持久的。这部作品确立了中国官方历史记录的传统。一些当代中国学者甚至声称,它确立了中国文化中的人文主义信仰。在司马迁之前,历史记录是比较零散的,由不同的社会团体承担。在司马迁之后,历史记录变得更加集中,获得了朝廷的直接关注。《史记》还为学者们进行历史研究或写作创造一套标准。第一则标准是关于历史记录的范围。从汉代开始,中国的历史写作主要集中在帝王事迹以及重大历史事件的发展过程。第二则标准是历史记录的严谨性。中国的历史学家开始采用更加严格和科学的方法来记录历史,目的是尽可能地做到秉笔直书,并将他们的工作与以前的记录进行对照。最后,《史记》标志着一种新的历史学方法的出现,它结合了政治学、经济学和其他相关领域的知识来编织一条复杂的叙述。这种方法可以说一直被中国学者所倡导,直到二十世纪初西方现代史学方法的引入。

在司马迁的同一时期,西半球也见证了著名历史学家的崛起。地中海世界在记录历史方面有丰富的惯例。2500多年前,古希腊人系统地记录和研究了过去的事件,像希罗多德和修昔底德这样的人物只是其中的两个例子。罗马人在继承了希腊人的文化后,进一步推动了历史学的发展。当时两位杰出的历史学家是李维(公元前59年至公元17年)和普鲁塔克(公元46年至120年)。李维以其对罗马历史的详尽研究和记录而闻名。虽然他在罗马历史学家中是独一无二的,因为他没有参与政治或宗教活动,但他从 "个人和道德的角度 "看待历史,也就是说,他从更感性或哲学的角度来解释过去。他是第一批从重要的个人和个性而非政治冲突的角度看待历史的历史学家之一。

李维的作品在西方历史学上留下深刻的印记。首先,他重塑了历史写作的风格,使之更容易被更多的人接受。他使历史变得更加生动,从而产生了共鸣和意义。这种重塑历史学写作的尝试的一例证据是李维作品中句法种类的增加。在某些时候,他利用较长与拥有众多从句的句子来描述一处场景的细节;在其他时候,他则会转而使用简短而精悍的句子来描述一次行动的快速性。另一例证据是他的措辞。此前,历史学的用词极为正式与没有感情。李维推翻了这一惯例,采用了广泛的诗意或戏剧性的词汇。这种写作风格上的重大变化给他的许多读者留下了深刻的印象,他们被他叙述的优雅与生动所深深吸引。从李维开始,历史将不再是一种只适合权贵的话题,而是一种任何有学术头脑的人都可以接触的话题。

其次,李维对历史中个人道德与个人性格方面的关注极大地影响了未来的历史学家和西方历史学的研究范围及重点。李维极为强烈地感受到了他那个时代道德的衰落,他指出:"如今你在一个人身上哪里能找到当年属于整个民族的谦虚、公平和高尚的思想?" 历史记录的责任应该是为个人和他们所属的国家提供范例和警告。因此,李维试图将历史从纯粹的政治研究转变为集中研究人性与社会环境中个人间内在互动的课题。历史学家应该对人类个体和社会进步的基本模式更感兴趣。李维启发了圣奥古斯丁等历史学家,甚至影响了启蒙运动时期欧洲思想家,如伊曼纽尔-康德或弗里德里希-黑格尔。例如,黑格尔将他的很大一部分注意力放在 "世界历史伟人 "上,并在作品中详细解释了推动社会发展的根本因素。

综上所述,通过对中国商代甲骨文、汉代史学家司马迁的《史记》和罗马史学家李维的历史作品的研究,可以确认,历史记录是不同历史时期文明中一项重要活动。当人们深入研究历史记录的动机时,问题是:历史的作用和价值究竟是什么?正如尼采所称,历史以各种方式为生命服务。对一些人来说,历史提供了勇气。"曾经存在的伟绩与伟人,至少曾经是可能的,而且很可能在某个时候再次成为可能"。有了这样的认识,雄心勃勃的人就能以更雄伟的胆量与决心采取行动。对其他人来说,历史提供了一种归属感。在历史中寻找归属感是中国的一个传统。每个人都与他们的家庭历史、城市历史和国家历史有着密切的关系。当历史能够为个人注入生命时,那么历史学就是人们试图寻找这种强大的生命力来源的自然过程。

在现代背景下,虽然人们必须承认历史的重要性,但对历史持批判态度也是至关重要的。当历史将生命注入个人时,它也有能力将其触角悄悄地捆绑在个人身上,进而"扼杀 "他们。历史往往保留了生命力,但却不能创造生命力。人们可以很容易地利用历史来满足他们与记忆联系的欲望,但最终会发现很难创新或打破历史惯例与传统。随着此过程的展开,人类有可能会衰败、堕落。现在,人们必须提出新的灵感和想法来驾驭日益复杂的社会。随着突破性技术的不断进步,社会互动的潜规则也在不断变化。为了跟上这种忙碌的发展步伐,人们必须有力量粉碎和消解过去的元素,分析与批判阻碍创造力的历史片段。随着时间的推移,这种 "非历史性 "的生活方式可能变得更为关键。我并不是说,历史记录在未来应该完全被废除。相反,无论对于个人,还是国家,真正重要的是掌握利用历史的钥匙,且同时始终意识到历史潜在的限制与危险。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/608

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权