On Experiential Learning 论体验式学习

A Reflection on the Experiential Learning Trip to Inner Mongolia

Today, thanks to the rapid development of the information age and the continuous innovations of global educators, there are various ways to learn. Arguably, the most common learning method is reading books or using the internet in a classroom setting. However, as the amount of information that a person must absorb in a lifetime has been exponentially increasing, this traditional method is showing deficiencies. Not only is such a method less efficient when faced with an immense pool of knowledge, as books contain a fixed amount of information, but it also decreases the will to learn in many individuals. For these reasons, the concept of “experiential learning” emerges relevantly. This kind of learning abandons the classroom setting and instead focuses on the impact of experiences on the individual learner. It aims to provide the learner with vast opportunities to step into the environment and utilize all the senses to engage actively with elements in reality. Experiential learning comes in four stages: Thinking, Acting, Experiencing, and Reflecting. I will draw on a recent personal experience of experiential learning during a school trip to Inner Mongolia and discuss how this kind of learning allows one to immerse, learn about learning itself, and acquire physical and mental freedom.

Experiential learning is first associated with the idea of full immersion. This association makes this form of learning stand out, as other means to obtain information usually do not involve a thorough immersion in an environment. When one attempts experiential learning, they sharpen their senses to react to the surrounding elements. For example, one part of my school trip to Inner Mongolia was learning how to build a yurt, the traditional Mongolian shelter. After a short briefing, the whole team tried to construct a yurt from a pile of materials. During this construction process, I smelled the original materials of the yurt, touched the connecting segments of the structure, experimented with different positions to place the connecting beams, and observed the relation between the position of the door and the direction of the wind. This experience of building a yurt is an example of experiential learning. Whereas in a classroom setting, one might learn by reading a passage about the principles of yurt construction or hearing a lecture about the topic, in the experiential setting, one is encouraged to employ every part of one's body to conduct trials and think under a highly relevant and authentic setting. Experiential learning allows me to be fully immersed in the yurt-building activity. As a result, by smelling the materials, I can discern their unique characteristics and even trace them back to their origins in the nearby grasslands or forest areas, weaving these pieces of information neatly into my mind. Touching the structural points of connection further enables me to understand why the yurt can hold without a single nail, even in adverse climatic conditions. The magic of experiential learning is that through the complete immersion of the body in the environment, the learner can automatically remember and understand a vast array of information, further developing a will to explore.

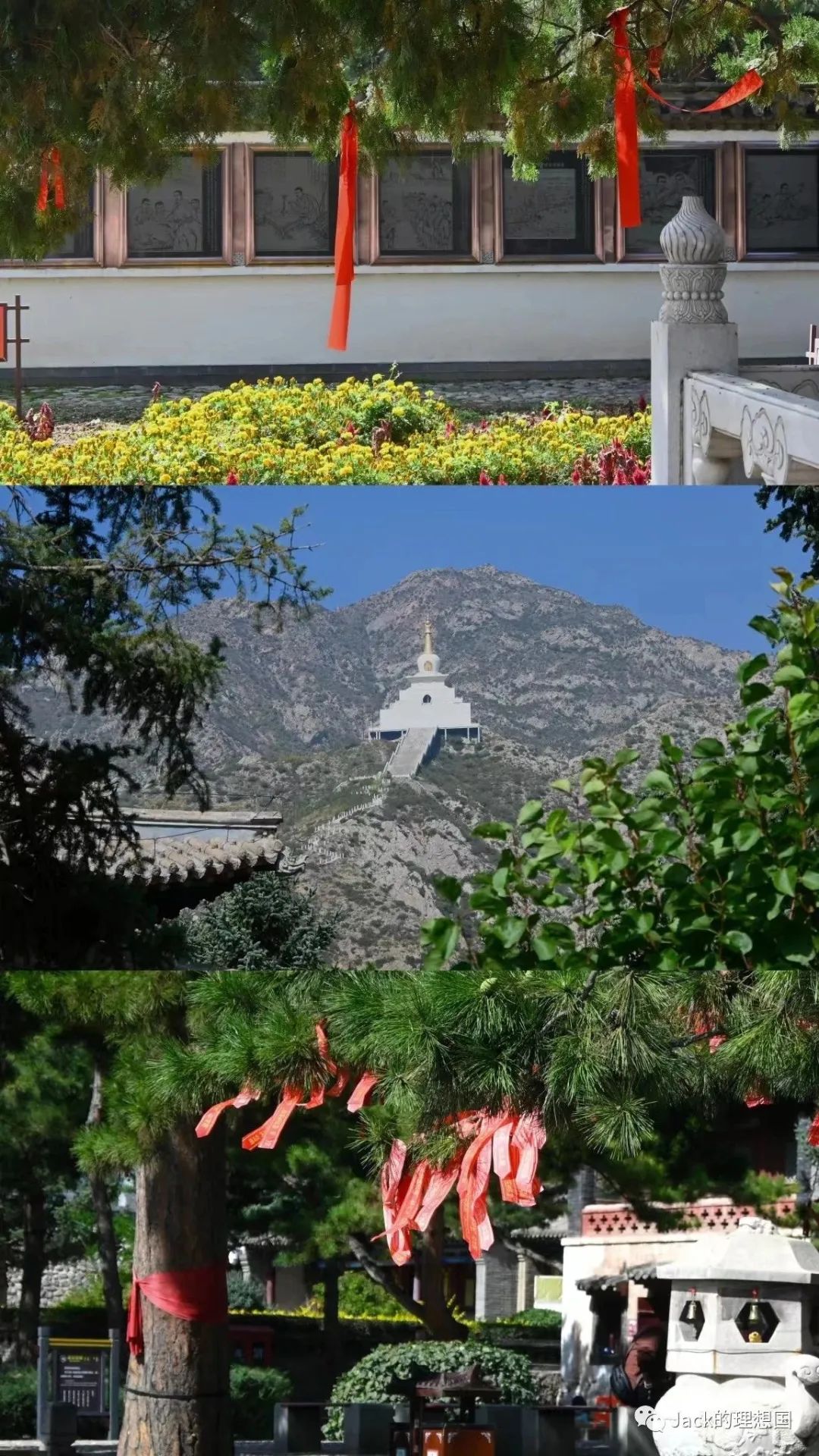

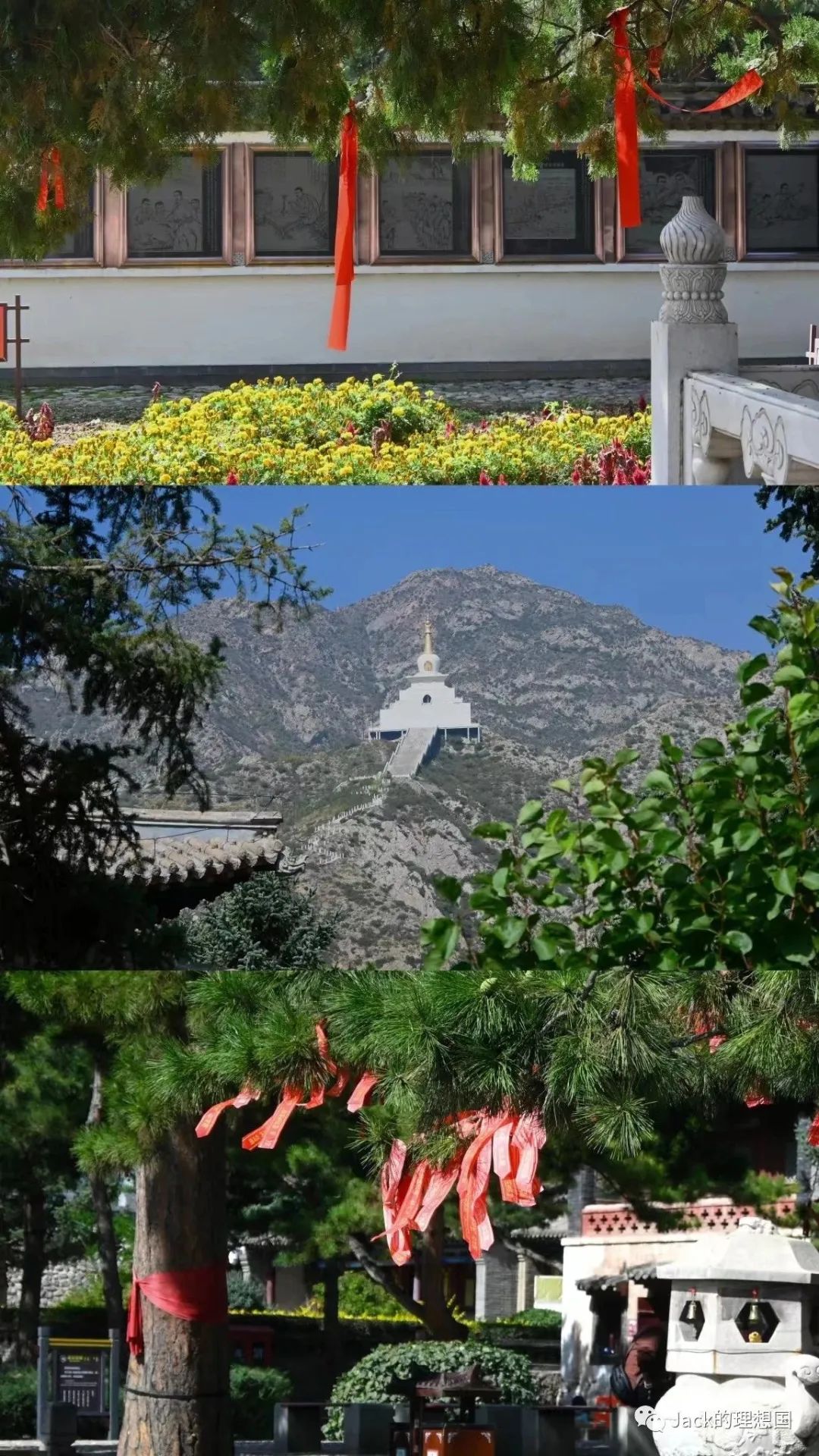

However, aside from providing an opportunity to immerse, experiential learning is one of the only channels that allow an individual to learn how they learn. Unlike the traditional book-reading method, experiential learning makes one thoroughly cognizant of what they are undergoing. Thus, although this kind of learning immerses the learner in experiences, it also gives that learner a holistic, bird-view perspective on the learning process. For instance, I visited a Tibetan Buddhist temple during the Inner Mongolia journey. To learn about the essence of Tibetan Buddhism and the practices of local monks, I stepped into the most sacred buildings in the temple and, after reading the inscriptions on the walls, experienced some of the practices myself. I knelt and worshipped Buddha, circled some buildings clockwise three times, and gazed at the massive wall paintings of prominent religious figures. Following the trip, as I reflected upon it, I realized that the primary method I utilized to gain knowledge about the temple and Tibetan Buddhism was by transforming myself into a person in their history who attempted to live like a monk. This thorough “role-play” allowed me to spot the core elements of the prevalent religion in Inner Mongolia. In this example, the “reflection” stage of experiential learning made it possible for me to be conscious of my decisions and actions in the temple and look back at the path I took to learn.

Finally, experiential learning nurtures physical and mental freedom in the learner. History shows that some of the most influential educators, political leaders, and innovators benefitted immensely from experiential education. Confucius, Siddhartha Gautama, Aristotle, and many more developed their worldviews and continued to bring far-reaching ideas because they were almost constantly on the road, learning from meditation, communication with others, and experiences. These individuals shared a common point – they were free. Confucius was physically and mentally free when he traveled around the significant states from 497 to 483 B.C.E.; Siddhartha Gautama possessed an innate spiritual freedom that could not be imprisoned; Aristotle was free when he explored the Mediterranean Islands and Asia Minor. Their freedom gave them the boldness and ingenuity to think ahead of their time and transform inspirations and observations into solid, powerful ideas. Without freedom, it would be improbable for Confucius to come up with his school of thought that aimed to fix the social and political issues of his time, as he could not visit and study so many states. It would be quite difficult for Siddhartha Gautama to reach enlightenment without his spiritual freedom that prodded him to break social obstacles and traditions in his day. It would be implausible for Aristotle to write about poetry, zoology, politics, and ethics if he only stayed in his native Greece and did not study the wider world.

What empowered these figures with their freedom? Experiential learning is a major aspect of the answer. Experiential learning opens the horizon for an individual. It pushes the learner to realize that there are countless journeys to embark on, innumerable opportunities to take in the wonders and unique characteristics of cultures, and moments when it is acceptable to rest to feel the rhythm of nature. This realization kindles a firm determination in the learner to break the limits they set on themselves and leave the familiar zone behind to hear new stories. The actions of breaking limits and leaving the familiar zone constitute freedom. One night in the adventure to Inner Mongolia, I woke up at four to leave my yurt and take in the starry sky. Looking above and around, the night sky was dotted by radiating points of white and yellow. At that moment, I forgot everything about stars from textbooks and documentaries and was struck by awe and fascination. What followed was an upsurging want of adventure, a want that disregarded the possible hurdles and only yearned for freedom. Under the starry dome, a message resonated, reminding me that the world is boundless. What I have known and seen compose only a few dots in the vast realm of stories and experiences. The sudden burst of spiritual freedom was exciting yet calming simultaneously, a mix of thrill and contemplation.

It is inaccurate to hook experiential learning completely with the goal of acquiring points of knowledge, though such an association is important. Compared to traditional ways of learning, there is a more holistic force at play in learning through experience. It dives to the root of knowledge and the act of learning itself. Through a complete engagement with the subject, the learner absorbs the essence of it and develops an effective demand for more such experiences. Experiential learning connects an individual with the real world, the world one can see, touch, hear, smell, and feel. As the virtual environment becomes ever more prevalent, it is worth noting the value of this learning as an anchor that ties the learner to reality, cultivating their passion for real visions, textures, sounds, scents, and emotions. Without this anchor, individuals may fall victim to the maze of virtuality that traps them in a forged realm, becoming numb. In this quick-paced world, careful navigation is the only way to ensure one’s identity remains intact. Experiential learning is a potion the educated can drink to find and pick their paths prudently. It ensures that the learner stays calm even when faced with the virtual world's lures and can always live as a lively, real human being.

内蒙古体验式学习之旅的一次反思

脚踩坚实的土地,头顶绚烂的星空…

如今,由于信息时代的飞速发展,全球教育工作者不断创新,学习的方法愈发多样化。在这些方法中,最常见的便是在课堂上阅读书籍或网络学习。然而,随着人一生中必须吸收的信息量呈指数级增长,这种传统方法正显现出不足之处。面对浩如烟海的知识,这种方法不仅效率低下,因为书本包含的信息量是固定的,而且还会降低人的学习意愿。因此,"体验式学习 "的概念应运而生。这种学习在短期内摒弃了课堂,而是注重体验对学习者的影响。它旨在为学习者提供大量的机会,让他们走进现实环境,运用各种感官积极探索现实中的各种因素。体验式学习分为四个阶段: 思考、行动、体验、反思。我将以最近在内蒙古游学期间的一次体验式学习的亲身经历为例,讨论这种学习方式如何让人沉浸其中,了解学习过程本身,并获得身心自由。

体验式学习首先与 "完全沉浸 "这一概念联系在一起。这一点使这种学习方式脱颖而出,因为其他获取信息的途径通常不会让学习者完全沉浸在某种环境中。当一个人尝试体验式学习时,他的感官会变得敏锐,从而对周围的元素做出反应。例如,我的内蒙古体验式学习之旅的一部分就是学习如何建造蒙古包。在简短的介绍之后,整个团队尝试用一堆原始材料从零开始,搭建出一座能立住的蒙古包。在搭建过程中,我细闻蒙古包建筑材料的原始味道,触摸建筑结构的连接部分,尝试将连接梁以不同角度放置在不同位置,观察分析门的坐标与风向的关系。建造蒙古包的经历就是体验式学习的一个例子。在课堂上,学生可能会通过阅读有关蒙古包建造原理的文章或聆听有关该主题的讲座来学习,而在体验式学习中,学生则被鼓励运用身体的每一部分,在一个极其相关与真实的环境中进行试验及思考。体验式学习让我能够完全沉浸在建造蒙古包的活动中。因此,通过闻材料的气味,我可以分辨出材料的特性,甚至可以追溯它们在附近草原或森林地区的起源,并在脑海中将这些信息整齐地编织在一起。触摸结构上的连接点更能让我透彻地理解为什么即使在恶劣的气候条件下,蒙古包也能在没有一颗钉子的情况下坚固如初。体验式学习的神奇之处在于,通过让身体完全沉浸在环境中,学习者可以自动记住并理解大量信息,并产生探索的欲望。

然而,除了提供沉浸的机会,体验式学习也是让个人学习他是如何学习的唯一渠道之一。与传统的读书学习方法不同,体验式学习让人彻底认识到自己正在经历的。因此,虽然这种学习方式让学习者沉浸在体验中,但同时也让学习者以一种整体的、鸟瞰式的视角来看待学习过程本身。例如,在内蒙古的旅程中,我参观了一座藏传佛教寺庙。为了了解藏传佛教的精髓与当地僧侣的修行方法,我走进了寺庙中神圣的建筑,在阅读了墙上的介绍文字后,亲自体验了一些修行方法。我向佛祖表达了敬意,顺时针绕建筑三圈,凝视了墙上巨大的宗教人物画。旅行结束后,当我回顾这次旅行时,我意识到我用来了解寺庙与藏传佛教的主要方法是试图将自己变成寺庙或藏传佛教历史上的一个个体,试图抓取僧侣生活的一些微小片段。正是这种 "角色扮演 "让我发现了内蒙古盛行宗教的核心要素。在此例子中,体验式学习的 "反思 "使我能够意识到自己在寺庙中的决定和行为的意义所在,并回望自己的学习之路。

最后,体验式学习能培养学习者的身心自由。历史中一些最有影响力的教育家、政治领袖与创新者都从体验式教育中受益匪浅。孔子、释迦牟尼、亚里士多德以及更多的历史人物之所以能够形成个人的世界观并不断提出影响深远的思想,是因为他们几乎一直在路上,从冥想、与他人的交流和经验中学习。这些人有一个共同点--他们都是自由的。孔子从公元前 497 年到公元前 483 年周游列国时,身心是自由的;释迦牟尼拥有与生俱来的精神自由,这种自由是无法禁锢的;亚里士多德探索地中海群岛与小亚细亚时也是自由的。他们的自由提供了超前思考的胆识与志气,将灵感及观察转化为坚实有力的思想与推断。如果没有自由,孔子就不能提出旨在解决当时社会及政治问题的儒家学派,因为他不能访问并研究如此多的国家。释迦牟尼如果没有精神上的自由,就很难在他的时代打破社会障碍与传统,达到觉悟与启蒙。如果亚里士多德只能留在在他的故乡希腊,而不研究更广阔的世界,那么他无法完成如此广泛的,关于诗歌、动物学、政治与伦理学的作品。

是什么赋予了这些人物自由的力量?体验式学习是答案的一个重要方面。体验式学习为个体翻开地平线,开阔了视野。它促使学习者认识到,有无数的旅程可以开始,有无数的机会可以领略各种文化的奇妙与独特之处,也有无数的时刻可以让身心休息,纯粹感受自然的节奏。这种认识点燃了学习者坚定的决心,一种打破自己给自己设定的限制的决心,一种离开熟悉的故土,去聆听新的故事的决心。打破限制,走出故土,这诠释了自由。在内蒙古的探险中,有一天晚上,我凌晨四点起床,走出蒙古包,欣赏星空。放眼望去,夜空中点缀着白色与黄色的亮点。那一刻,我忘记了教科书与纪录片中关于星群的一切,只是被一种敬畏所震撼。随之而来的是对冒险的强烈渴望,这种渴望无视可能存在的障碍,只向往自由。在星空下,有一条要旨引起了我的强烈共鸣,提醒我世界是无边无际的,我的所知所见,不过是浩瀚的故事与经历的夜空中几处微小的亮点。突然迸发的精神自由让人兴奋,同时又让人平静,这是一种激动与沉思的深刻融合。

将体验式学习与获取知识点完全挂钩是不准确的,尽管这种联系很重要。与传统的学习方式相比,体验式学习有一种更全面的力量在起作用,它深入到知识与学习行为本身的根源。通过对学习主题的全面参与,学习者吸收了其精髓,并对更多此类体验产生了有效需求。体验式学习成功地将个人与现实世界联系起来,即一个人可以看到、触到、听到、闻到并感到的世界。随着虚拟环境的日益普及,这种学习的价值是,它是将学习者与现实联系起来的锚,培养个体对真实的视觉、质感、声音、气味与情感的热情及渴望。如果没有这锚,一个人可能会落入虚拟世界迷宫的陷阱,被困在一个伪造的领域,在这个过程中变得逐渐麻木,陷入精神空虚,甚至精神死亡。在这个快节奏的世界里,只有小心航行,才能确保个人的身份保持不变、不被四分五裂。体验式学习是受教育者审慎地寻找与选择道路的工具,它保证了个体永远都能在虚拟世界的多重诱惑下保持镇定,时刻回想真实世界的价值所在,做一名真正鲜活的“人”。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/619

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权