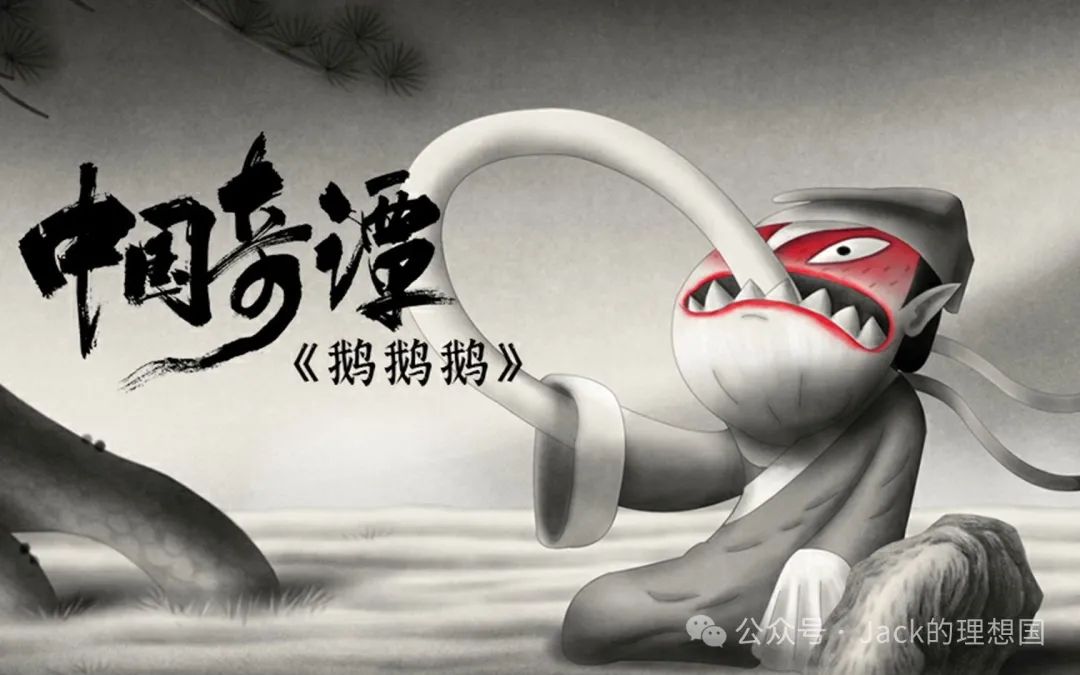

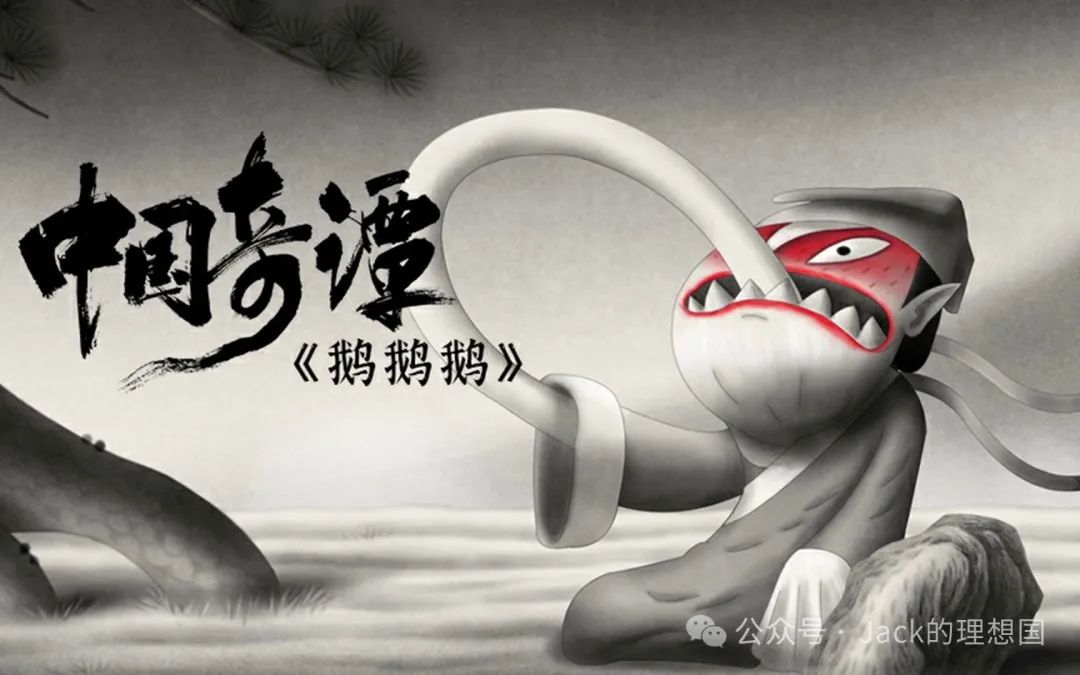

The Human Heart in "Goose Mountain" 《中国奇谭》系列之《鹅鹅鹅》评论

Introduction

Chinese classical philosophies partially revolve around the concept of human “suffering.” This concept does not simply denote physical pain or illness. It represents the spiritual challenges that arise from endless forms of desire. By desire, Chinese philosophers refer to craving pleasure, material goods, and immortality, all of which are wants that can never be satisfied. To reflect the essence of this philosophy,director Rui Hu produced a second episode of Yao-Chinese Folktales for BiliBili’s young users and potentially all Chinese netizens. Titled “Goose Mountain,” this short, animated story follows a young vendor carrying a goose cage passing the ghostly Goose Mountain. He encounters a hobbling Scholar Fox, who insists on entering the goose cage and traveling with the vendor to the top of the mountain. Upon reaching the top, the Fox reveals his lover, the Rabbit Spirit, who then reveals her lover, the Boar Spirit, who finally reveals his lover, the Swan Spirit. Subsequently, all these characters vanish, leaving the vendor alone with a single earring from the Swan Spirit, whom he has developed an affection for.

This animation revolves around the concept of “the human heart.” The author believes the director elaborates on four Chinese philosophical themes to position this universal concept in a Chinese context. To portray these themes more uniquely and appealingly, the production team employs different techniques ranging from the addition of symbolism to the use of the black-and-white color scheme, from the adoption of an open narrative to the rendering of a magical realism style. This article will begin by exploring the four themes that are well-embedded in this animation. Then, this article will analyze the effects of the techniques utilized to present these themes from the perspective of Chinese traditions.

Thematic Explorations Regarding “The Human Heart”

(The vendor reshapes the appearance of the mountains)

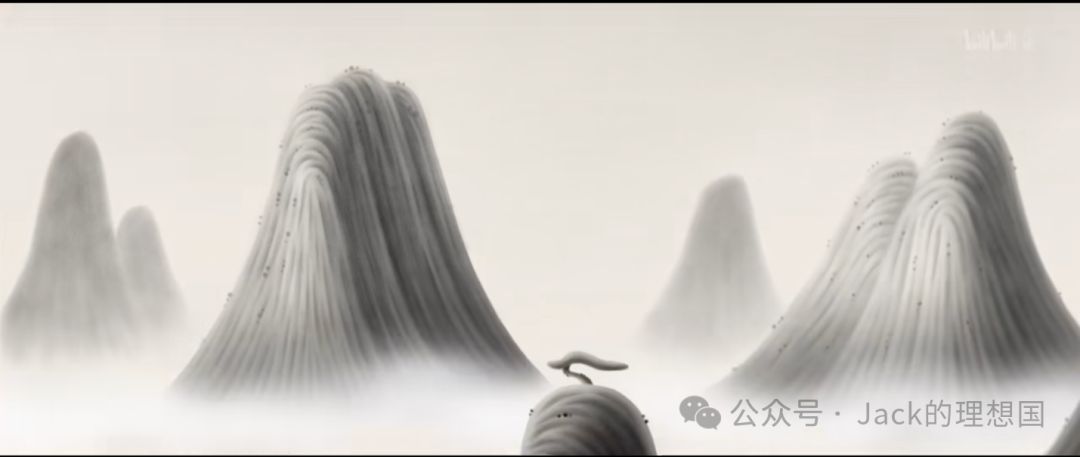

To display the inherent depth and multi-dimensional nature of the concept of “the human heart” in Chinese philosophy, the director crafts several angles and themes to discuss this concept. The first significant theme to note is that, ultimately, the human heart constantly changes. This animation's external environment, the Goose Mountain, never physically turns different. However, the vendor’s inner condition is in constant flux, from fear to uncertainty to seeming pleasure to a sense of loss. The changes in the vendor’s heart cause him to “reshape” the appearance of the mountains. For example, in one scene, the mountains and the horizon suddenly shrink to a size well below the vendor's stature, suggesting that the character’s view of the setting changes dramatically at that moment. In Buddhism, it is often taught that the true source of change and transformation lies within the human heart rather than the external environment. The mind is the principal actor in creating our experience of reality. External events are filtered through one’s understanding and emotions. Thus, the mind ultimately shapes and alters an individual’s perception of the world; the heart is the creator of happiness or suffering.

(In one scene, the Rabbit Spirit (the larger shadow) pulls out the Boar Spirit (the smaller shadow) from her body)

(In another scene, the Boar Spirit (the larger shadow) pulls out the Swan Spirit (the smaller shadow) from his body)

The second theme about “the human heart” is that desires stem from other desires in an endless cycle. The consecutive scenes where one spirit “pulls out” another spirit from its body symbolize desires engendering more desires. In Buddhist philosophy, desires lead to action, which in turn leads to more desires, perpetuating a cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. More specifically, an initial want might spawn secondary wants to fulfill it. For example, craving wealth might lead to wants for a higher-paying job, status, or power. Desires can be compelling because they are rooted in the mind and heart. Thus, like any other kind of fiction, desires display immense sway over an individual’s emotions and beliefs.

(The main character, the vendor, loses a sense of direction)

The third theme present in this animation is the prevalence of illusions in life. The spirits, even the mountains in the background, might not be real. They can be fictional entities, ripples in the heart, or even dreams conceived by the vendor. These entities influence the direction the main character chooses to travel, pulling him away from the village's original destination. Illusions form fabricated yet powerful images that trick the brain. This theme reminds this essayist of Taoism philosophy, specifically the discussion of reality in the story “Zhuang Zhou and the Butterfly Dream,” in which every event seems illusional. The animation further attempts to remind viewers that illusions stem from the unsettled nature of one’s heart. The unsettledness can be derived from fear, anxiety, lust, greed, or avarice.

A final theme in this animation is that everyone may be confined in a “cage” set up by someone else. The setup where the Spirits pull one another from each body suggests that one’s understanding of the surrounding environment and interactions with others might be indirectly controlled or influenced. Such a philosophy, yet again, resonates with Buddhist traditions. Buddhists believe there is a “cage of conditioning,” the limitations and constraints imposed by an individual’s conditioned existence. From birth, one can be influenced by various factors such as social norms, family and upbringing, or education and media. These influences create a mental and emotional "cage" that confines the perception and understanding of reality.

Techniques to Present These Themes

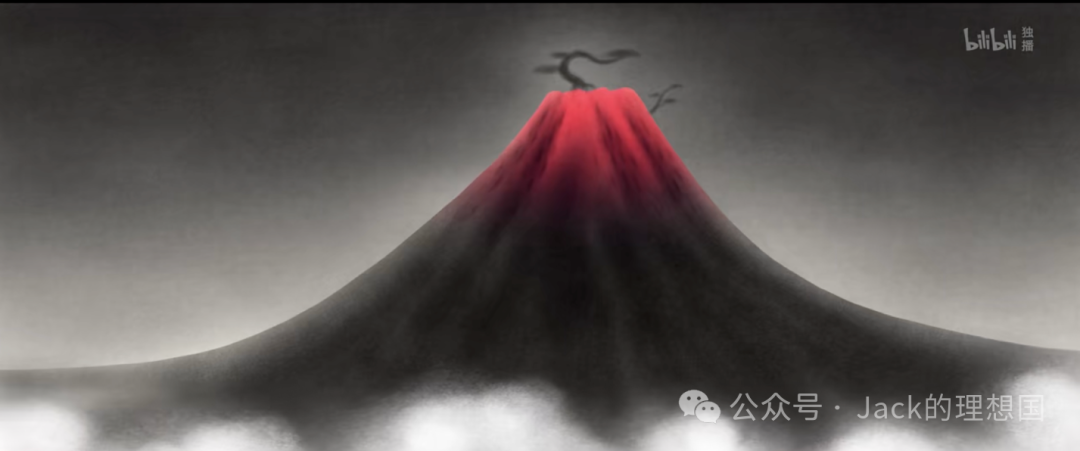

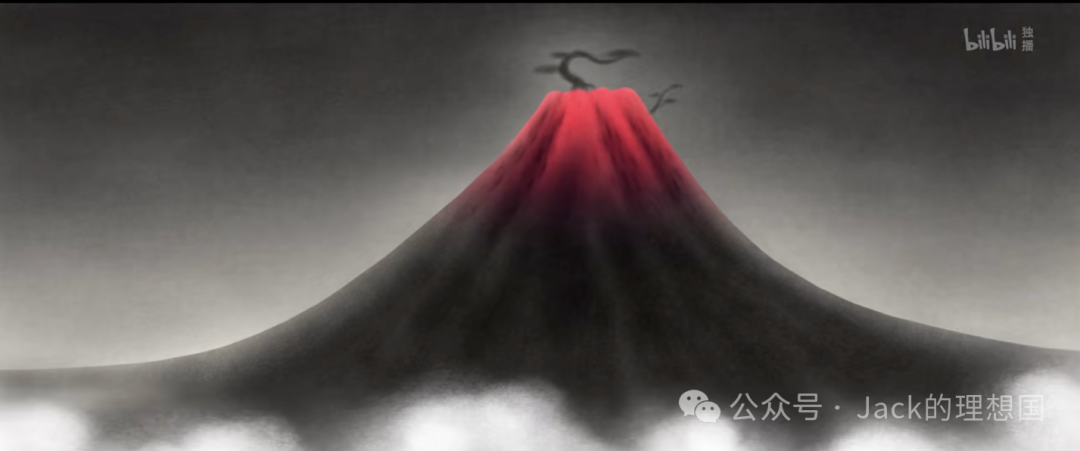

First, the director employs environmental and animal symbols to highlight the various wants and illusions in one’s heart. One of the most notable symbols in this animation is the mountain ranges in the background. The mountains are towering and seem to extend beyond the horizon. Such a scene conjures up a sense of majesty and even oppression, symbolizing the powerful, impactful desires that form formidable barriers, emerging one after another. When the Fox Scholar asks the vendor to take him to the peak of the tallest mountain, there is a sudden flash of red light on the peak, but the light passes away immediately. The mountain's peak represents the pinnacle of wealth, fame, and many other wants. However, the immediately fading light suggests that these wants are mere illusions that eventually disappear into the void. These wants and illusions do not objectively exist but are conjured up from the vendor’s mind.

(The Fox Scholar)

Additionally, animal symbols appear throughout this animation. The different spirits – the fox, the rabbit, the boar, the swan – might represent different desires. For example, the Fox Scholar, a Fox Spirit himself, might represent lust, and the boar might represent gluttony or the insatiable desire to eat and drink. Through this group of animal symbols, the director effectively portrays all kinds of wants that might plague an individual’s mind, allowing the audience to relate these desires to similar sensations they experience daily. The authorial choice to make these spirits appear from another one ties the animation back to the theme that desires stem from other desires.

Aside from subtly inserted symbols, the director's magical realism style, which is in line with other episodes ofYao-Chinese Folktales, merits discussion. The style is especially fitting for this animation because its origin is chiefly from a “Zhi Guai” short story called “The Yang Xian Scholar,” written in the sixth century C.E. In Chinese literary tradition, “Zhi Guai” short stories are known to be about mysterious, strange, and supernatural topics. Thus, the director’s decision to fuse uncanny and supernatural elements into the narrative of this animation pays homage to the story’s roots. Magical realism helps the animation reinforce its themes. First, since the story is set in a relatively realistic setting, audience groups from a wide range of backgrounds can come to comprehend and relate their living environments with that of the story. From the storytelling perspective, the magical realism style twists an otherwise plain and familiar storyline, creating a sense of absurdity. This slight absurdity that many viewers might develop as they watch the strange spirits appear one after another reminds viewers of the theme that life itself is often full of absurd illusions.

Finally, the director uses a black-and-white color scheme, with dots of red here and there, giving the entire animation an unmistakable traditional Chinese style. Not only does the color scheme remind Chinese viewers of many old-school films made decades ago, but it also imitates Chinese wash paintings in a vibrant and picturesque fashion. In many scenes, such as the mountains moving in the background, the audience can feel that wash paintings from centuries ago have come back to life. In Chinese cultural convention, there is a saying that “black and white, virtuality and actuality, complement each other.” This saying suggests that Chinese artists may use the black-and-white color scheme to portray the duality of virtuality and actuality. Returning to the context of this animation, the black-and-white scheme does effectively fulfill this purpose. The flashing black-and-white shadows on the vendor’s face, the mountains' surface, and the spirits' bodies allude to the theme of illusions in reality. Furthermore, the shadows might even represent the uncertainty in one’s heart as they confront all kinds of desires. An individual is often tempted to satisfy a desire, yet sanity tries to hold them back. The black-and-white scheme subtly portrays this inherent duality in the human heart.

Conclusion

While the animation’s content aims to revolve around the concept of “the human heart” and explore the themes mentioned above, the animation’s larger goals are to display Chinese historical literary culture and storytelling. To this end, it has achieved remarkable success. The animation’s narrative is quite implicit and open to interpretation. Told in a pantomime format, the story offers no voiceover or character conversation, leaving ample room for imagination. After watching the animation, viewers cannot resist themselves but be inspired from different angles. The ending, in particular, is intriguing. The vendor returns to his original position in life, shaping the storyline into a loop and adding yet another uniquely Chinese feature. The director invites the audience to think about the impacts that the vendor’s experience would have left on him in the long run.

The embedded philosophy of this animation provides interpretations of the nature of human desire and suffering that speak to a global audience. The director conveys a motif that resonates across cultures and borders. The film explores the universal human experiences of desire and uncertainty. It alludes to the pursuit of inner peace, a pathway to a life free of illusions and suffering. Ultimately, “Goose Mountain” reminds us that searching for inner peace is a most arduous and sinuous quest, not because there are physical barriers. The difficulty lies in the strenuous work of transforming one’s own mind and way of being. As Buddha claims, “The way is not in the sky. The way is in the heart.”

The images in this article were taken from: https://www.bilibili.com/bangumi/play/ss39707?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0

简介

中国传统的古典哲学一直在探讨一个核心概念,即人间的“苦”。从道家到佛家,“苦”不仅仅指身体上的疼痛或疾病,它指的是无尽的欲望所带来的精神挑战。这里的欲望是指对快乐、物质财富和永生的渴望,而所有这些都是永远无法满足的欲望。为了反映这一哲学思想的精髓,导演胡睿为 BiliBili 的年轻用户乃至所有中国网民制作了《中国奇谭》第二话,名为《鹅鹅鹅》。这一话讲述的是一个背着鹅笼的小商贩经过崎岖的鹅山,路途中他遇到了一位充满魅惑的狐狸书生,它坚持要进入鹅笼,与小贩一起前往山顶。到达山顶后,狐狸书生请出了他的心上人兔精,兔精又请出了她的心上人野猪精,野猪精又请出了她的心上人天鹅精。随后,所有这些角色都消失了,只剩下小贩和他对之产生好感的天鹅精的一只耳环。

这部动画片围绕 “人心 ”这一概念展开,将这一普世概念置于中国文化背景之下。本文作者认为,导演在四个中国哲学主题方面均有深刻的讨论。为了更独特、更吸引人地描绘这些主题,制作团队采用了不同的技巧,从象征主义到黑白配色的使用,从开放式叙事到魔幻现实主义风格的渲染。本文将首先探讨这部动画中蕴含的四个主题,然后,本文将从中国传统的角度分析表现这些主题的手法所产生的效果。

关于 “人心 ”的主题探索

为了说明中国古典哲学中“人心 ”这一概念的内在深度与多维性,导演从多个角度探讨这一概念。第一个值得注意的重要主题是,归根结底,人心总是变幻莫测的。这部动画的外部环境--鹅山,从未改变。然而,商贩的内心状态却在不断变化,从恐惧到不确定,从快乐到失落感。这种内心的变化促使他不断重塑心中鹅山的形象。例如,在一个场景中,山脉和地平线突然缩小到远低于小贩的身材,这表明人物对环境的认识在那一刻发生了巨大的变化。正如佛教所认为的那样,变化与转变的真正源泉在于人的内心,而不是外部环境。心灵是创造个体现实体验的主要角色,外部事件同样是通过人的理解与情感过滤的。因此,思想最终会塑造、改变个人对世界的感知,心灵是幸福或痛苦的创造者。

(兔精从身体中拉出野猪精)

(野猪精从身体中拉出天鹅精)

关于 “人心 ”的第二个主题是,欲望源于其他欲望,循环往复。一个精将另一个精从身体中 “拉出 ”的连续场景象征着欲望产生更多的欲望。在佛教哲学中,欲望导致行动,行动反过来又导致更多的欲望,生死轮回,生生不息。更具体地说,最初的欲望可能会催生满足它的次级欲望。例如,对财富的渴望可能会导致对高薪工作、地位或权力的次级渴望。欲望可以产生巨大的力量,因为它们植根于思想与内心。因此,就像任何其他类型的故事一样,欲望对个人的情感与信仰有着巨大的影响力。

这部动画的第三个主题是生活本就是充满幻象的。各种动物精,甚至背景中的山峰,都可能不是真实的,它们可以是虚构的实体,可以是心中的涟漪,甚至可以是小贩构想的梦境。这些元素影响着主人公选择的旅行方向,使他偏离村庄最初的目的地。幻觉又进一步形成了虚构却强大的幻象,迷惑着心智。这一主题让本文作者想起了道家哲学,特别是《庄周梦蝶》故事中对现实与虚幻梦境的讨论,故事中每一件事似乎都可能是虚假的。这部动画片还试图提醒观众,幻觉源于人内心的不安定,这种不安可能来自恐惧、焦虑、欲望与贪婪。

这部动画的最后一个主题是,每个人都可能被关在别人设置的 “笼子 ”里。一个动物精从另一个精的身体里被弹出,被控制的设置表明,个体对周围环境的理解以及与他人的互动可能会受到其他人、环境因素的间接控制或影响。这种理念与佛教传统再次产生了共鸣。佛教徒认为存在一个 “条件的牢笼”,即个人的存在就意味着他会被施加各种限制与约束。一个人从出生开始,就会受到各种因素的影响,如社会规范、家庭和成长环境,或教育和媒体。这些影响造成了心理与情感的 “牢笼”,限制了对现实的感知与理解。

表现这些主题的技巧

首先,导演运用环境与动物象征来突出人心中的各种欲望及幻象。这部动画中最显著的象征之一就是背景中的山脉。山脉高耸入云,似乎延伸到了地平线之外。这样的场景给人一种威严甚至压迫的感觉,象征着强大而有冲击力的欲望,形成了一道又一道坚不可摧的屏障。当狐狸书生要求小贩带他到最高的山顶时,山顶上突然闪过一道红光,但红光马上就消失了。山顶代表着财富、名声和许多其他愿望的顶峰。然而,马上消失的光芒表明,这些愿望只是幻觉,最终会消失在虚空中。这些愿望和幻觉并不客观存在,而是小贩头脑中的幻想。

此外,动物象征贯穿了整个动画。不同的精--狐狸、兔子、野猪、天鹅--代表不同的欲望。例如,狐狸书生本身就是狐狸精,他可能代表着淫欲,野猪精可能代表着贪得无厌的饮食欲望,等等。通过这组动物符号,导演描绘了困扰个人心灵的各种欲望,让观众将这些欲望与他们日常经历的类似感觉联系起来。作者选择让这些精从另一个精身体里出现,更将动画与 “欲望源于其他欲望 ”的主题联系起来。

除了巧妙地插入象征之外,导演的魔幻现实主义风格也值得讨论,这种风格与《中国奇谭》的其他剧集一脉相承。《鹅鹅鹅》故事的灵感来源之一是写于六世纪南朝时期的志怪故事《阳羡书生》。在中国文学传统中,“志怪 ”小说以神秘、诡异、超自然的题材特点著称。因此,导演决定在这部动画片的叙事中融合不可思议和超自然的元素,正是向《鹅鹅鹅》故事的原创致敬。魔幻现实主义有助于动画传递其主题。首先,由于故事背景相当真实,更多来自不同背景的观众群体可以理解并将自己的生活环境与故事环境联系起来。从叙事的角度来看,魔幻现实主义风格将原本平淡无奇的故事情节进行多重变形,营造出一种荒诞感。观众在看到一个又一个奇怪的精出现时,就会产生这种荒谬感,让观众进一步联想到生活本身往往充满了荒诞的幻觉这一主题。

最后,导演使用了黑白配色,并在其中点缀了红色,使整部动画具有鲜明的中国传统风格。这种色彩搭配不仅让中国观众联想到几十年前的许多老派电影,更重要的是,它模仿中国水墨画的手法极为生动,如诗如画。在很多场景中,比如山峦起伏的背景中,观众仿佛能感觉到几百年前的水墨画活了过来。在中国的文化传统中,有 “黑与白、虚与实,才能相映成趣”的说法,中国艺术家可以运用黑白配色来描绘虚实的双重性。回到这部动画的语境中,黑白配色的确有效地实现了这一目的。小贩的脸、山的表面和精的身体上闪烁的黑白影子暗示了现实中的虚幻这一主题。此外,这些影子甚至可以代表一个人面对各种欲望时内心的彷徨与反复的波动。个体常常会被诱惑去满足某种欲望,但理智又试图阻止他们,黑白画法巧妙地描绘了人类内心固有的这种双重性与持久的挣扎。

结语

这部动画片的内容旨在围绕 “人心 ”这一概念,探讨上述主题,然而更大的目标则是展示中国古典的哲学思考与延续下来的历史文化。为此,动画片取得了不俗的效果。这部动画片的叙事遵循中国传统,含蓄且具有宽阔的自由诠释空间。故事以默剧的形式讲述,没有画外音,也没有较多人物对话,至此给观众留下充分的想象空间。看完动画后,观众会不由自主地从不同角度受到启迪。尤其是结尾,十分耐人寻味。小贩回到了生活的原点,他仍是处在鹅山中,孤寂一人,这使故事情节满足中国传统的周而复始的“圆形”叙事,又增添了一个独特的中国特色。同时,导演邀请观众思考小贩的经历又会给他带来哪些长远的心智上的影响。

这部动画片所蕴含的哲理为全球观众从中国视角诠释了人类欲望与苦难的本质。导演传达了一个跨越文化与国界的主题,影片探讨了人类普遍的欲望与生活的不确定性,暗示了对内心平静的终极追求是摆脱虚无的幻想与物质的痛苦的途径之一。《鹅鹅鹅》提醒人们,寻求内心的平静是人生最艰巨、最曲折的探索,但这并不因为探索路径上存在的物理障碍,真正的困难乃是克制个体头脑以冲动处理世界的方式,屏蔽扰乱心灵的杂音。不断磨练心灵是达到启蒙的唯一途径,正如佛陀曰:"道不在天,道在心中"。

该文章图片来源于:https://www.bilibili.com/bangumi/play/ss39707?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/643

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权