Chinese Culture in "Old Man Yang" 《中国奇谭》系列之《小卖部》评论

Introduction

In Yao-Chinese Folktales, while several stories are rooted almost entirely in mythology or fiction, some take direct inspiration from fundamental changes. The seventh episode, “Old Man Yang,” exemplifies the latter approach. Directed by Gu Yang and Liu Kuang, the plot follows the trail of an old man named Yang in a historical “hutong,” where he has lived most of his life. The story focuses on his close interactions with the people and objects in the hutong, such as the stone lions by a gate, the roaming cats, and a yellow weasel. Upon knowing that due to urbanization efforts, Yang must leave his hutong home behind and switch to living in a modern apartment, the otherwise abiotic objects magically spring to life to thank him for his efforts to preserve them.

Structurally, the animation abides by a principle common in Chinese stories: it creates an implicit buildup of emotions from the beginning and powerfully releases all feelings towards the end. At the start of this animation, the narrative is relatively flat, and viewers have no clear idea about the depth of the relationship between Yang and the hutong. Towards the end, all the emotions and relations that Yang has built with the elements in the hutong are released in a spectacular burst. Such a narrative structure draws the audience in as the plot progresses, creating a powerful resonance with them at the end. With a touch of warmth and nostalgia, the story revolves around the central concepts of memory and connection. This review will discuss the presentation of these concepts by first explaining the themes spun around them and then the specific techniques to shape the themes and ideas.

Thematic Explorations into “Memory” and “Connection”

(A scene at the very beginning of the animation, juxtaposing the hutong and the modern skyscrapers)

The directors subtly weaves together several themes to thoroughly explore the concepts of “memory” and “connection.” Some of these themes are larger in scope than others, but all demonstrate the cornerstone status of such concepts in Chinese cultural films since the early 2000s. The first minor theme is urbanization’s impact on old-style living and the attached memories. This theme has been explored in many similar contemporary works. Unlike many works that blame urbanization as the ultimate culprit for destroying traditional lifestyles, the directors leave a more open discussion for the viewers in this animation. Urbanization efforts may have accelerated the removal of old buildings, hutongs, and traditional landscapes, replacing them with modern facilities. However, are fostered human connections and segments of a past lifestyle wholly lost in urbanization? The production team invites their audience to contemplate the severity of a conflict between modernity and tradition.

Another minor theme regarding “memory” and “connection” well-presented in the animation is preserving memories eternally in the heart. This theme, again, traces its roots back to Chinese cultural traditions. Chinese culture believes that memories must be passed down from generation to generation for the continuity of a family, a community, or even a nation. The animation pays homage to such philosophy by displaying memories with almost eternal characters once they reside in an individual’s heart. Even if the physical symbols of these memories disappear, the past will still retain its weight. Yang, the protagonist, treats the elements in his life with an innate, pristine kindness, allowing him to form intrinsic bonds with them.

(Old gadgets in Yang’s hutong home)

The animation's final theme is the ability of an individual to hold on to an era’s memories as time rapidly progresses. This theme poses the extending question: To what extent can an individual stand firmly and not be swept passively into the furious tides of time? Yang attempts to resist the pulls from a changing time. For instance, he insists on keeping his “old gadgets” no matter who tries to persuade him to throw them away. Even when he must accept a new residence in high-rise apartments, he returns to the hutong many times a month to re-experience a fading past.

Specific Techniques to Portray the Themes

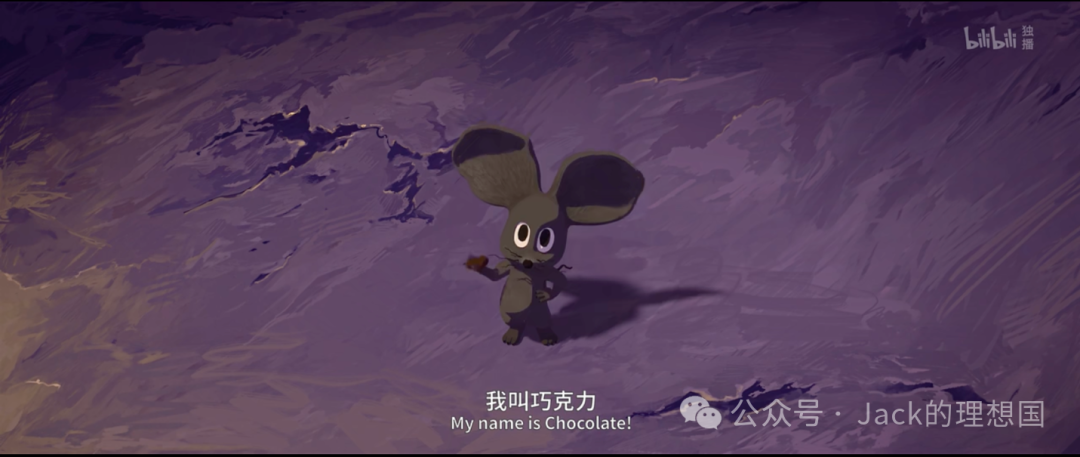

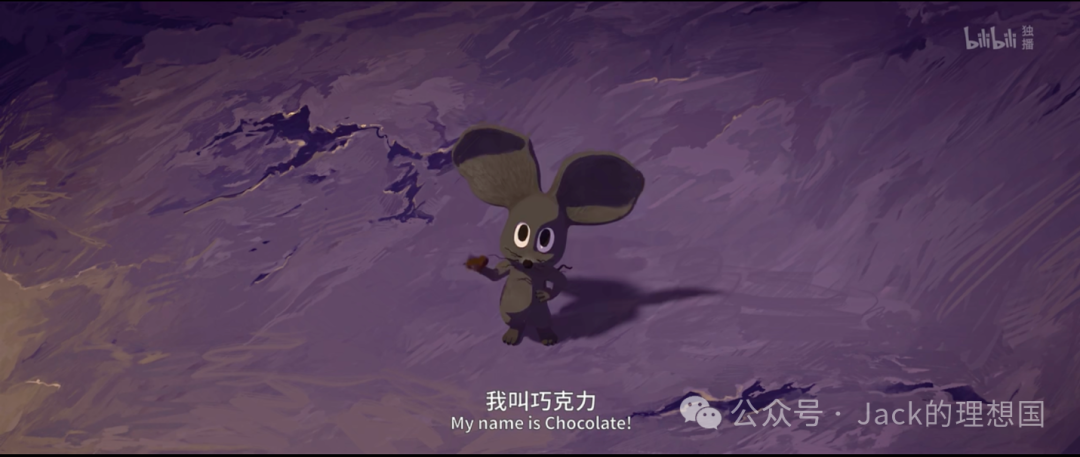

(A lottery ticket that turns into a mouse)

(Stone lions that possess spirits)

To highlight and establish links between these themes, the animation creators utilize various techniques to achieve their purpose. One of the most notable techniques is adopting a magical realism style, like how the directors of The Night at the Museum sprinkle magic into an otherwise genuine world. In this animation, the mystical elements include a lottery ticket that turns into a mouse, stone lions that possess spirits, and other seemingly inorganic objects that can suddenly burst into life. These mystical elements are not only vibrant, but they also own “personal” stories and backgrounds distinct from each other.

(The real world, tangible but flat)

(The world of memories, vivid and emotional)

The addition of elements of magical realism helps the directors to juxtapose two parallel worlds. One world is the real one, tangible but flat, where memories often fail to take a firm grip amidst the rapidly changing times. Another world is constructed from memories and connected emotions with every other aspect of life. The animation gives the audience a visual microcosm of this world in the scene where the decaying old temple renews its vitality, bursting with technicolor and a dazzling exuberance of hutong memories. The magical realism style is rendered to such an extent in this work, reminding the viewers of traditional animalistic beliefs – every piece of matter has a spirit. Tying back to “memory” and “connection,” this authorial decision effectively claims that memories are active and may form a fictional, iridescent world of stories. No matter how reality spins and changes, this world of memories is constant and transcends the boundaries of time.

(The walls of the hutong separate the inner environment from the outer world)

Zooming in from the general style of magical realism, the directors embed a group of powerful symbols into the film’s setting and plot. The hutong setting serves a dual symbolic meaning. It is a barrier to modernity. The walls of the hutong separate the inner environment from an outer world that is rapidly urbanizing and relentlessly chaotic, creating a quaint utopia within. It is quite difficult for residents in the hutong to access the outer world and adapt to changes in lifestyle. From another perspective, the hutong is a sanctuary for memories and for those who hope the past will not be forgotten as societies build and realize an ever more unpredictable future.

(The two sides of the temple)

Another impactful environmental symbol is the old temple, set to be closed and “renovated.” The temple serves a double meaning as well. First, it definitively represents the impact that modernization brings to traditional culture. Although the animation does not provide the purpose of the renovation, viewers can deduce that the renovated temple, taking a different outer form, would probably lose some of its original value and stories. Through this symbol, the directors encourage the audience to ponder the eventual fate of objects, buildings, and relations forged in the past. Second, when Yang visits the temple, the scene where it springs back to life symbolizes the power of an individual to keep memories alive and breathe new life into the past. “Alive” memories do not necessarily manifest in other physical objects or beings. Instead, the vitality of memories exists in one’s heart and can radiate new colors if treated with kindness and care.

(The swarm of flies)

The symbol of the swarm of flies above the hutong buildings is one of the most intriguing small details in the animation. The wind and other factors may impact their flight pattern, but the flies always stick together and tend to light. The swarm of flies may be a recurring symbol of human society. Each fly might be tiny and insignificant, easily swayed by the wind. However, once an individual fly bonds with other flies to form a swarm, they can stay intact even if the environment changes. The power and togetherness of a community are not forged by any single individual but by the tight connections that individuals build. The bonds that Yang establishes with the people and the objects in the hutong allow him to be aware of changing times and to always find his identity in his community.

Presentation of Chinese Culture to a Global Audience

(The red doorknob, a uniquely Chinese element)

In this animation, the directors make some quite nuanced thematic choices that permit this work to resonate with broader target audience groups, even with foreigners who might not be familiar with Chinese history and culture. The motifs of “memory” and “connection” are universal by nature and explored in literary works and films beyond Chinese borders. Yang's well-embedded touch of nostalgia and concern about the future are emotions shared by anyone who feels weak in the tides of history. Yet simultaneously, these motifs are portrayed in a pure Chinese cultural setting. Elements like the hutong, red doorknobs, and stone lions permeate throughout the plot – these are exclusively Chinese and speak volumes about the potential of this animation to present Chinese culture in a vivid, story-like way.

For this animation to be accepted and, more importantly, understood by a foreign audience, the Chinese elements and details can be explained in greater detail. For instance, the production team can consider making certain shots of traditional Chinese architectural details longer so that foreign viewers have more time to observe and think about the roles of these details in the architecture. Additionally, by adding character voiceovers or including explanations of the functions of particular Chinese objects in conversations, the expression of Chinese culture can be more explicit.

Finally, overall, dramatic conflicts can be made stronger throughout the storyline. For example, to portray Yang's struggles with moving away from the hutong and into a high-rise apartment somewhere in the modern world, the directors can study the possibility of letting Yang have more direct arguments with younger characters. Moreover, the directors can consider further delineating Yang’s inner conflicts with himself. Has he ever tried to convince himself to relinquish the memories in the hutong and embrace the new lifestyle in the city? Has he ever felt mental distress and pain upon the realization that he is about to say farewell to not only the hutong but a lifestyle that he has hailed for decades? With more substantial dramatic conflicts, the storyline’s message and themes can be more resounding to a global audience.

Conclusion

“Old Man Yang,” being a short animation for under 20 minutes, offers an insightful and uniquely Chinese perspective to the discussion of the characteristics of human memories and connections. The directors take a creative spin on the concept of “Yao,” or monster, portraying the “monsters” and spirits in this work as vivid pieces of memory fused into the daily lives of the hutong’s residents. Perhaps the ultimate message of this animation is as such: Some elements in life may not come back after they are lost, but we can “store” them in our hearts and pass them down to others around us. Physical landscapes of the world change, but stories forged collectively remain eternal.

The images included in this article are mainly taken from the original animation on BiliBili: https://www.bilibili.com/bangumi/play/ep706672?spm_id_from=333.337.0.0

简介

在《中国奇谭》中,有几个故事几乎完全源于神话或虚构,但也有一些故事直接从现实世界的变化中获得灵感。第七话《小卖部》就是这一种创作方式的典型代表。该片由顾杨、刘旷执导,讲述了一位“杨大爷”在一条他生活了大半辈子的历史悠久的北京胡同里的故事。故事聚焦于他与胡同里的人和物的本质的、亲切的互动,如门边的石狮子、游荡的猫和一只黄鼠狼等等。当他知道由于城市化进程,他必须离开胡同的家,转而住进现代化的公寓时,这些原本非生物的东西都神奇地焕发在他的生命里,感谢他为保护它们所做的努力。

在结构上,这部动画片遵循了中国故事的一个常见原则:从一开始就营造出一种隐含的情感积淀,并在结尾时强烈地释放出所有情感。在动画的开头,叙事比较平,观众对杨大爷和胡同之间的深层关系并不完全清楚。然而到结尾处,杨大爷与胡同里的各种元素建立起来的情感和关系得到了淋漓尽致的释放。这样的叙事结构随着情节的推进吸引着观众,在结尾处与观众产生了异常强烈的共鸣。故事围绕着 “记忆 ”与 “链接”这两个核心概念展开,带着淡淡的温情与怀旧。本评论将讨论这些概念的表现形式,首先解释围绕这些概念展开的主题,然后讨论塑造主题与概念的具体技巧。

对 “记忆 ”与 “链接”的主题探索

(影片开始的一个镜头,其中背景的现代楼房与古香古色的胡同建筑在画面中并置在一起)

导演们巧妙地将几个主题交织在一起,深入探讨了 “记忆 ”与 “链接”的概念。这些主题有的范围较大,有的范围较小,但都表明了这些概念自 21 世纪初以来在中国文化电影中的基石地位。第一个小主题是现代城市化对旧式生活与附着记忆的影响,这一主题在许多类似的当代作品中都有所探讨。与许多作品将现代城市化视为破坏传统生活方式的罪魁祸首不同,导演们在这部动画片中为观众留下了更开放的讨论空间。现代城市化进程可能加速了老建筑、胡同与传统生活景观的消失,取而代之的是现代设施。然而,在城市化进程中,人与人之间的联系与过去生活方式的片段是否完全被吞噬?制作团队邀请观众思考现代与传统之间冲突的广泛性与严重性。

动画中另一个关于 “记忆 ”与 “链接 ”的小主题是将记忆永恒地保存在心中。这一主题同样可以追溯到中国的文化传统。中国文化认为,记忆须代代相传,才能延续一个家庭、一个社区乃至一个国家的故事。动画片通过展现记忆在个人心中的永恒性,向这种哲学致敬。即使这些记忆的物理象征消失了,过去却仍然会保留其分量。杨大爷以一种与生俱来的、质朴的善意对待生活中的各种元素,从而与它们结下了不解之缘。

动画的最后一个主题是,随着时间的飞速流逝,个人能否守住一个时代的记忆。这个主题提出了一个延伸问题:个人能在多大程度上在心中保持定力,不被动地卷入时代变动的狂潮?杨大爷在片中试图抵御时代变迁的牵引,例如,无论谁劝他扔掉家里的“老玩意儿”,他都坚持要留住它们。即使他必须接受高楼大厦的新住所,他每个月还是会多次回到胡同,重新体验逐渐消逝的过去。

描绘主题的具体技巧

(能变成一只老鼠的兑奖卷)

为了突出这些主题并在主题之间建立联系,动画创作者运用了各种技巧来达到目的。其中最显著的一种手法就是采用魔幻现实主义风格,导演们在一个完全真实的世界中撒入魔法。在这部动画片中,魔幻元素包括一张会变成老鼠的兑奖卷、拥有灵魂的石狮子以及其他看似无机的物体,它们会突然迸发出生命的活力。这些神秘元素不仅充满活力,还拥有 “个人”故事与不同的背景。

(现实的世界,有形但却往往平淡)

(记忆的世界,富有生动性与多元情愫)

魔幻现实主义元素的加入有助于导演将两个平行世界并置:一个是真实的世界,有形但却往往平淡,在瞬息万变的时代中,记忆往往无法牢牢附着在这个世界中。另一个世界则纯粹由记忆构建而成,情感与生活的方方面面息息相关,紧密相连。动画为观众展现了这个世界的一个视觉缩影:破败的老庙重新焕发出勃勃生机,迸发出炫目的色彩,胡同里的记忆也随之被赋予生命。魔幻现实主义风格在这幅作品中被渲染得淋漓尽致,让观众联想到传统的泛神论信仰--每一种物质都有灵魂。联系到 “记忆 ”和 “链接 ”的概念,作者的这一决定有效地提出记忆是活跃的,可以形成一个虚构的、斑斓的,富有故事的世界。无论现实如何旋转变化,这个记忆的世界是恒定的,超越了时间的界限。

(胡同的围墙将内部环境与现代城市相阻隔)

在魔幻现实主义的总体风格上,导演在影片的背景与情节中植入了一组强有力的象征。胡同的背景具有双重象征意义。它是现代性的屏障,胡同的围墙将胡同内部环境与快速城市化与无情混乱的外部世界隔离开来,在胡同内部创造了一个古色古香的乌托邦。胡同里的居民很难接触到外部世界,也很难适应生活方式的变化。从另一个角度看,胡同是记忆的避难所,也是那些希望过去不会被遗忘的人的避难所,这些人像杨大爷一样,认为社会可能正在建设与实现一个更加不可预测的,缺少“人情味儿”的、冷酷的未来。

(老庙的双重含义,在第二张图片中,重新焕发生机)

另一个具有影响力的环境象征是即将关闭与 “翻新 ”的老庙。这座寺庙也有双重含义。首先,它明确代表了现代化对传统文化的重置。虽然动画中没有说明翻新的目的,但观众可以推断出,翻新后的寺庙在外观形态上可能与原来不同,很可能会失去一些原有的价值、故事及历史记忆。通过这一象征,导演鼓励观众重新思考过去形成的物品、建筑与人际关系的最终命运。其次,当杨大爷参观庙宇时,庙宇重新焕发生机的场景象征着个人保持记忆、为过去注入新生命的力量。记忆 “活着 ”并不一定意味着它们会以另一种实物或存在的形式表现出来。相反,记忆的生命力存在于一个人的心中,只要善待和呵护,就能焕发出新的色彩。

(腻虫群)

胡同建筑上方的腻虫群象征是动画中最耐人寻味的小细节之一。风和其他因素可能会影响它们的飞行方向,但虫们总是粘在一起,趋于亮光。腻虫群可能是人类社会的一个象征性缩影。每只虫可能都是微不足道的小生命,很容易被风吹的东倒西歪。然而,一旦一只虫与其他虫结合成群,即使环境发生变化,它们也能保持完整的集体形态。一个群体的力量和凝聚力不是由单个个体形成的,而是由个体之间建立的紧密链接形成的。杨大爷与胡同里的人和物建立的联系,让他在时代变迁中不至于迷失方向,并始终无论时代怎么变,都能在旧社区中找到归家的感觉,守住自己独有的身份。

向全球观众展示中国文化,讲好中国故事

(朱砂门环)

在这部动画片中,导演们在主题上做出了一些细致入微的选择,使这部作品能够与更广泛的目标受众群体产生共鸣,甚至是那些可能并不熟悉中国历史和文化的外国人。记忆 “和 ”链接"这两个主题具有普遍性,在中国以外的文学作品与电影中也经常有过探讨。杨大爷在该作品中展现的一丝念旧和对未来的担忧,是任何一个在历史潮流中时常感到脆弱的个体都会有的情感。但同时,这些主题又是在纯粹的中国文化背景下描绘出来的。胡同、朱砂门环、石狮子等元素贯穿整个剧情--这些都是中国独有的元素,充分说明这部动画片有潜力以生动、故事化的方式展现中国文化,体现中国哲学与社会价值观。

为了让外国观众接受这部动画片,更重要的是让他们理解这部动画片,可以对其中的中国元素和细节进行更详细的解释。例如,制作团队可以考虑将某些中国传统建筑细节的镜头加长,让外国观众有更多时间观察和思考这些细节在建筑中的作用。此外,通过增加人物配音或在对话中解释特定中国物品的功能与文化意义,可以更清晰地表达中国文化的底蕴。

最后,总体而言,导演组可以加强整个故事情节中的戏剧冲突。例如,为了刻画杨大爷搬离胡同、住进现代社会高楼公寓时的心理挣扎,导演可以研究让杨大爷与年轻角色有更直接的对峙。此外,导演还可以考虑进一步刻画杨大爷的内心冲突。他是否曾试图说服自己放弃胡同里的记忆,接受城市里新的生活方式?当他意识到自己即将告别的不仅仅是胡同,而是一种他赞美了几十年的生活方式时,他是否感到过精神上的苦恼与痛楚?有了更强烈的戏剧冲突,故事情节的信息与主题才能更深远地与全球观众的经历共鸣。

结语

作为一部不到 20 分钟的动画短片,《小卖部》在讨论人类记忆与链接的特点时,提供了一个极具洞察力且独特的中国视角。导演们对 “妖”的概念进行了创造性的诠释,将作品中的 “妖怪”和魂灵描绘成生动的记忆碎片,与胡同居民的日常生活融为一体。也许,这部动画片最终要传达的信息是,生活中的一些元素失去后可能不会再回来,但我们可以将它们 储存在心中,并传递给身边的人。世界的物质景观会日新月异、不断发生剧变,但集体吟诵的故事与代代相传的回忆却在人们对生活的信仰中始终可以是永恒的。

以上文章的图片均来源于BiliBili《中国奇谭》之《第七话:小卖部》影片,链接:https://www.bilibili.com/bangumi/play/ep706672?spm_id_from=333.337.0.0

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/642

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权