Links Between East and West 52 - State Creation 东西方的连接52 - 城邦的创立

On the Emergence of the State

Where does the state come from? What prompted people to build the earliest city-states? These are profound political questions debated for centuries by philosophers and political theorists. Thomas Hobbes claimed that life was nasty, brutish, and short. Individuals, hence, came together and submitted themselves to a greater authority to prevent the spread of violence. The fear of violence or the desire to live harmoniously as a collective group led to the creation of a state. However, using historical examples, this essay will point out an alternative explanation for the birth of a state. The first states were glued together not as shelters from violence, as Hobbes believed, but by economics. Economic needs in agricultural societies drove people to coalesce into more complex forms of organization that could serve such needs.

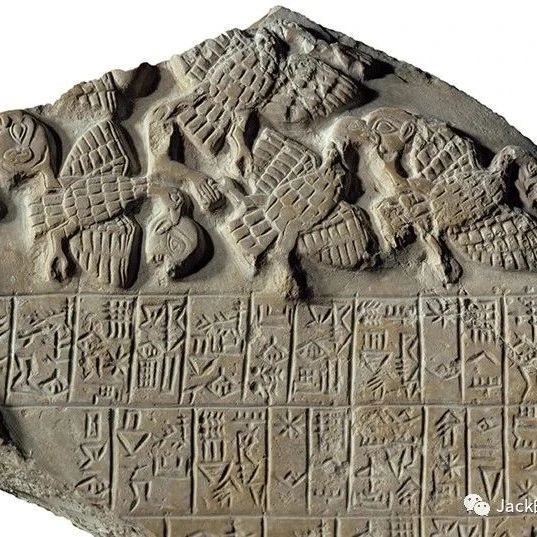

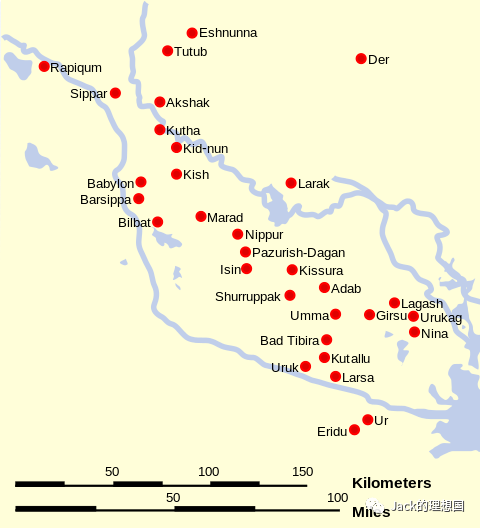

(The city-states of Mesopotamia, c. 3000 B.C.E.)

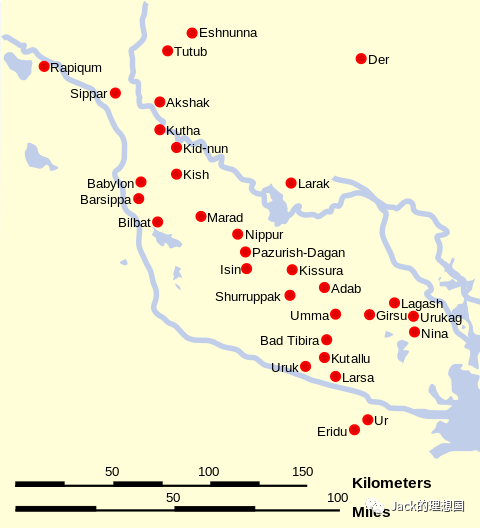

The Fertile Crescent is home to some of the world’s oldest settlements. The Mesopotamian civilizations that developed along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers date back over 5,000 years, earning them the title “the cradle of civilization.” As Robert Allen, Leander Heldring, and Mattia Bertazzini argued, economic considerations based on the changes of the two rivers strongly correlate to the rise of the Mesopotamian city-states. In their paper, the authors investigate “whether the timing of changes to a river’s course had anything to do with when the number and size of settlements grew.” This investigation method is reliable. When the paths of these rivers shifted, some ancient farmers were left without water for their crops, so they had to think of different ways to transport water to their irrigation fields. Some of these ways might have required the centralization of cooperative effort.

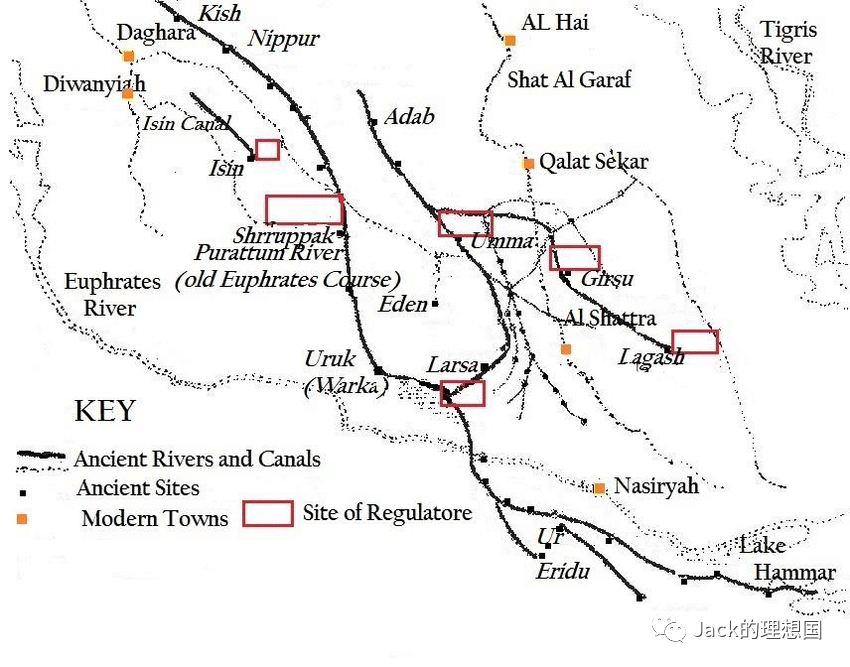

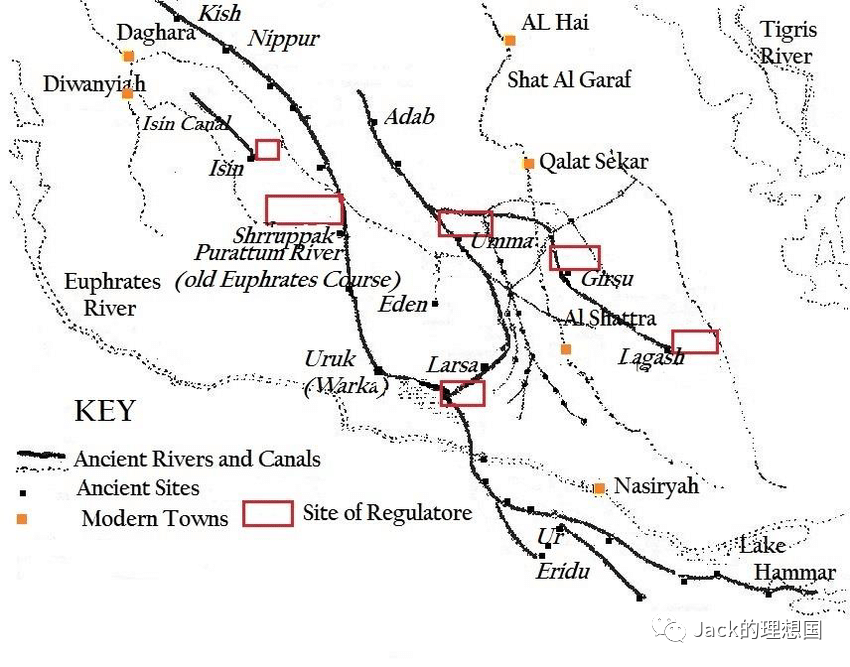

Mr. Allen and his co-authors looked more specifically at the effect of the first recorded shift at around 2850 B.C.E. This time coincided with the emergence of several early city-states. When the rivers changed their course, the Mesopotamians could choose to revert to nomadism or a “state of nature,” as Hobbes proposed. Or they could cooperate and build systems to ferry water from distant rivers. The study revealed that a “5km-by-5km square in the basin left behind by a river was 14% more likely to have a settlement, marked by a public building such as a temple or marketplace, 150 years after the shift than in the 50 years before it. Each square was 12% more likely to have a built canal…” The Mesopotamians created five new cities and expanded previous ones along the river’s tributaries. Thus, establishing a more complex social and political order in the form of a city-state may be attributed primarily to the economic concerns of the Mesopotamians. When the rivers’ water was no longer available, they possessed an economic need to provide enough agricultural output for their rising populations. Such a need called for forming central governments that could build canals and invent new irrigation methods to meet the economic demands.

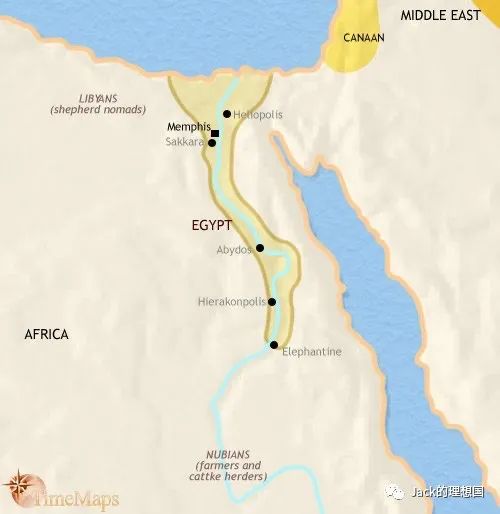

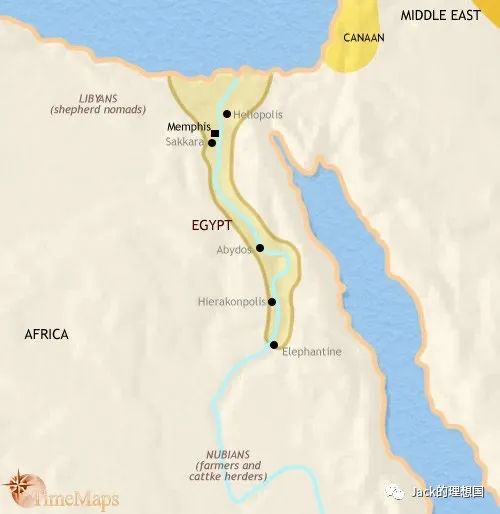

Similarly, in Egypt, the kings formed some of the early Egyptian states and cities for economic reasons. During the Early Dynastic Period, from around 3150 to 2686 B.C.E., Egypt became a unified kingdom. One of the most pivotal cities at this time was Memphis. The Early Dynastic Period kings established Memphis to realize some of the region's potential economic gains. The city was situated near the fertile delta region of the Nile River, where agriculture was booming. Since most economies during that historical period were almost purely agricultural ones that relied heavily on agricultural yields, the kings could control the vast surrounding farming areas by building Memphis. The fertility of the land also provided for a greater population, which translated into a stabler and larger labor force. Hence, Memphis could serve as a city-state where the kings organized a more centralized labor force for their needs. Finally, the Egyptian rulers could have established Memphis for trade purposes. It linked Egypt with the Levant, where trading various goods, such as different raw materials and agricultural products, was quite lucrative. Such a crucial economic nexus allowed the Egyptian kings to benefit from trade and further build their fledgling kingdom.

From the above selection of examples, people decided to construct states not because they feared conflict. Instead, economic reasons pushed individuals to erect governments that could centralize and manage resources more effectively. One may find many more examples elsewhere. For instance, in prehistoric China, many cultures developed sophisticated social and political organizations. But when archaeologists excavated many prehistoric sites, based on the abundance of agricultural products found, they hypothesized that many such minuscule states and cultures formed so that agriculture and trade could be more efficiently controlled. Plus, the lands of prehistoric China were sparsely populated, so intercultural warfare should not be severe to the point where it would become the sole factor prodding the early Chinese to establish complex states. Balancing and evaluating the different factors, many historians agree that the economy was once again the main driving force behind the creation of governments and states.

Overall, this essay believes that the origin of the state is more an economic question than a philosophical or political one. Hobbes’ argument that it was a fear of continuous conflict and violence driving people to form states underestimates the importance of the economy in the narrative. This underestimation is understandable, as Hobbes would have lacked the necessary tools and evidence to investigate his essential idea of the state of nature in history. Historians divide centuries of thinking on the origins of states into two groups. The first, including the prominent Karl Marx, argues that states arise from a social bargaining process. The elite grasp power to advance their interests and periodically provide services, such as basic infrastructure, education, or social security, to ensure the populace remains satisfied with their basic demands. However, this essay falls more into the second group of thinking, which includes philosophers like Locke and Rousseau. They claim that governments came into existence when people voluntarily chose to coordinate themselves, signing social contracts and swapping their individual freedom to be totally unrestrained for a state that protects their safety and other rights. Economic concerns usually guide and initiate this process of coordination. For today’s states, fulfilling economic needs is still a vital criterion for judging the effectiveness of governments. Hence, historians should spend more time investigating whether economic factors would similarly be at play in the formation of early states.

WORKS CITED

The Economist. “Where Does the Modern State Come From?” Economist.com, 20 Dec. 2023, www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/12/20/where-does-the-modern-state-come-from. Accessed 25 Dec. 2023.

论城邦的创立

城邦从何而来?是什么因素促使人们建立最早的城邦?这些都是哲学家与政治理论家们争论了几个世纪的深刻政治问题。托马斯-霍布斯(Thomas Hobbes)认为,生命是肮脏、残酷且短暂的。因此,个人聚集在一起,臣服于一种更大的权威之下,是为了防止暴力的蔓延。正是对暴力的恐惧或对作为一个集体和谐生活的渴望导致了政府与国家的建立。然而,本文将通过历史实例,对国家或城邦诞生的另一种解释进行论述。最早的国家并不是像霍布斯所认为的那样是为了躲避暴力。人们是因为对经济的考虑而最初结合在一起,形成城邦的。早期农业社会的经济需求驱使人们凝聚成更复杂的组织形式,以有效且稳定地满足这些需求。

(美索不达米亚的城邦,约公元前3000年)

新月沃土之上有一些世界上最古老的定居点。沿底格里斯河与幼发拉底河发展起来的美索不达米亚文明可以追溯到 5000 多年前,因此新月沃土被称为 "文明的摇篮"。Robert Allen、Leander Heldring 和 Mattia Bertazzini 三位历史学家认为,基于两条河流变化而诞生的经济考虑与美索不达米亚城邦的兴起密切相关。在他们的论文中,作者调查了 "河道变化的时间是否与定居点数量和规模增长的时间有关"。这种调查方法是可靠的,当这些河流的路径发生变化时,一些古代农民的庄稼就没有了水源,因此他们必须想出不同的办法将水运到灌溉田里,而其中一些方法可能需要更为集中的合作。

(黑虚线为美索不达米亚城邦间的运河)

Allen先生和他的合著者更具体地研究了公元前 2850 年左右第一次有记录的河道变化所带来的影响。当河流改变流向时,美索不达米亚人可以选择恢复游牧生活,这样的选择相当于回归霍布斯提出的 "自然状态"。或者,他们可以合作,建立从远方河流运水的系统。研究显示,"在河流留下的盆地中,一个五千米乘五千米的方形区域,在河道变化后 150 年出现定居点(以寺庙或集市等公共建筑为标志)的可能性比变化前 50 年高出 14%。每个定居点拥有已建运河的可能性要高出 12%......" 美索不达米亚人沿着河流支流新建了五座城市,并扩建了以前的城市。因此,美索不达米亚人决定以城邦形式建立更为复杂的社会和政治秩序可能主要归因于他们的经济考量。当河流的水不再可用时,他们就有了为不断增加的人口提供足够农业产出的经济需求。这种需求促使人们建立中央政府,修建运河,发明新的灌溉方法,以满足经济需要。

(古埃及地图,Memphis为孟菲斯)

同样,埃及早期的一些国家和城市也是国王出于经济原因而建立的。在大约公元前 3150 年到公元前 2686 年的早期王朝时期,埃及成为了一个统一的王国。孟菲斯是这一时期最重要的城市之一。早期王朝时期的初代国王建立孟菲斯是为了更好地实现该地区的一些潜在经济收益。这座城市靠近尼罗河肥沃的三角洲地区,那里的农业正在蓬勃发展。由于在那个历史时期,大多数经济体几乎都是纯农业经济体,严重依赖农业产量,因此国王们通过建造孟菲斯城,可以控制周围广阔的农业区。肥沃的土地也带来了更多的人口,从而转化为更稳定、更庞大的劳动力。因此,孟菲斯可以作为一个城邦,国王们在这里组织更集中的劳动力来满足他们的需要。最后,埃及统治者建立孟菲斯可能是出于贸易目的。孟菲斯连接着埃及和新月沃土一带,在连接两地的贸易路线上,各种商品(如不同的原材料和农产品)的交换相当有利可图。作为这样一个重要的经济纽带,埃及国王可以从贸易中获益,并进一步建设他们新生的王国。

从以上选取的例子来看,人们决定建立国家或城邦并不是因为他们害怕冲突。实际是经济原因促使人们建立能够更有效地集中和管理资源的政府。历史学家还可以在其他地方找到更多的例子。例如,在史前的中国,有许多文化的社会与政治组织方式发展得相当成熟。考古学家在发掘许多史前遗址时,根据发现的大量农产品残留推测,许多这样的小国与文化的形成是为了更有效地控制农业和贸易。再加上史前中国地广人稀,文化间的战争应该不会严重到成为促使中国先民建立复杂国家的唯一因素。因此,在对各种因素进行权衡和评估后,许多历史学家一致认为,经济再次成为建立政府或国家的主要推动力。

综上所述,本文认为国家的起源与其说是一个哲学或政治问题,不如说是一个经济问题。霍布斯认为是对持续冲突与暴力的恐惧促使人们建立国家,这一论点严重低估了经济因素在此历史叙述中的重要性。这种低估是可以理解的,霍布斯缺乏必要的工具与证据来研究“自然状态”此基本思想在历史中的实际样貌。历史学家将几个世纪以来关于国家起源的思想分为两类。第一类,包括著名的卡尔-马克思的理论,认为国家产生于社会讨价还价的过程。精英阶层掌握权力以促进个人利益,并定期提供服务,如基本的基础设施、教育或社会保障,以确保民众的基本需求得到满足。然而,本文更倾向于第二类观点,包括洛克、卢梭等哲学家的论述。他们认为,当人们自愿选择人际间的协调,签署社会契约,以完全不受束缚的个人自由换取一个保护每一位公民的安全与其他权利的国家时,政府就出现了。经济问题通常会引导并启动这一协调过程。对于今天的国家来说,满足经济需求仍然是判断政府是否有效的重要标准。因此,历史学家应该花更多的时间来研究经济因素是否同样会在早期国家的形成过程中发挥关键作用。

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/627

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权