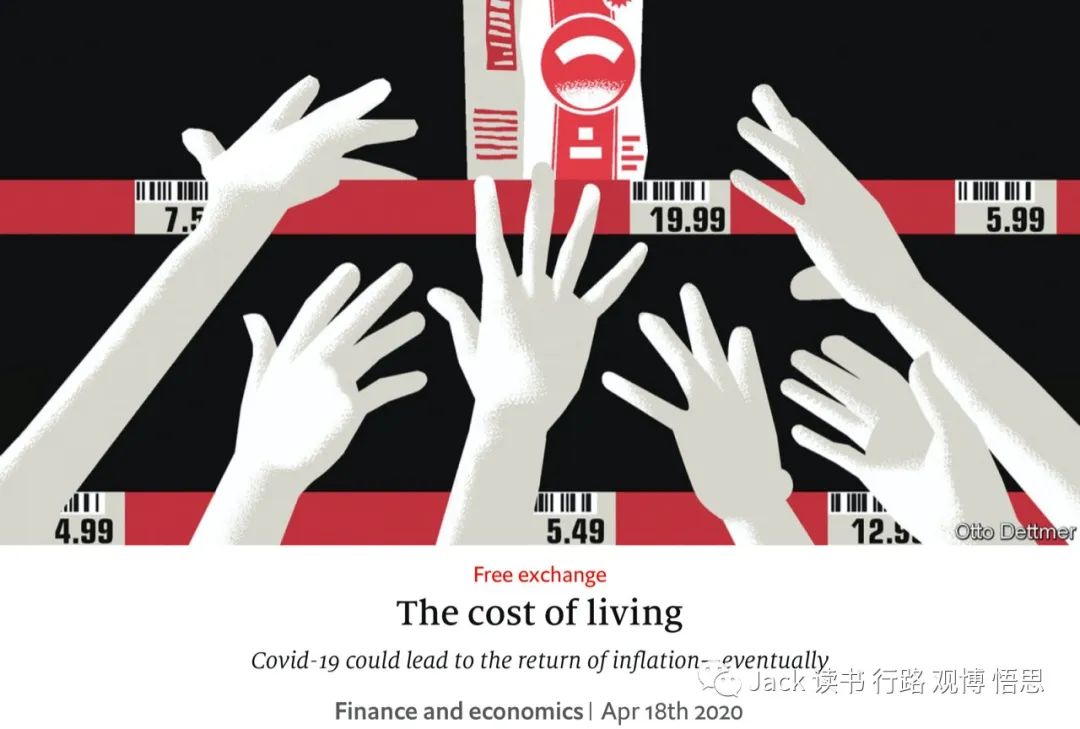

COVID-19 Series - 1: Inflation and Deflation

The Economist harnesses contrast between the inflationary as well as deflationary impacts brought by COVID-19 to support their claim that increases in price levels due to inflation are unlikely to materialize and that disinflationary pressures will remain. The Economist writes that the costs for some necessary supplies and services might "indeed rise sharply" while economies are "locked down". As an example, The Economist claims that the prices for medical equipment in the U.S. have "reportedly risen" as state governments compete for "scarce supply". But the Economist also points out that lockdowns not only interrupt supply chains, but they additionally undercut workers' "abilities to earn and spend". The Economist writes that "closing a restaurant" limits food-service supply, but it also means that "sacked waiters" and "kitchen staff" have no income. Since many workers see their earnings cut, they are likely to curtail spending. In some circumstances, the "drop in demand" induced by a supply shock may be larger than the "decline in supply" – a source of deflationary pressure rather than inflationary.

The Economist appeals to authority when the magazine mentions a new working paper co-written by several renowned writers from several prestigious universities to argue that rising price levels associated with inflation are unlikely to happen and that disinflationary pressures will remain. The Economist writes that according to the new paper, if "[certain] sectors" of the economy shut down completely, affected workers will "[reduce] their spending dramatically", suggesting the occurrence of deflation, unless the goods and services that can still be produced can substitute for those that cannot. However, the Economist argues, in the context of COVID-19, that substitution for goods and services that are not currently being produced is unlikely to happen. For instance, the "abrupt drop" in consumers' spending on plane tickets or hotel bookings is unlikely to be "offset by more purchases" of "teleworking software" instead, suggesting that deflationary pressures will rise severely. According to the new paper, deflationary pressures often beget a "Keynesian supply shock", where demand falls by more than supply.

Further, the Economist frequently uses scientific data to support their point that sustained increases in price levels associated with accelerating inflation are unlikely to materialize in the short run and that disinflationary pressures will remain. The Economist writes that in March 2020 the "annual consumer-price inflation" slowed in both America and the eurozone, compared with rates in February, suggesting that fewer goods are indeed being chased by even less spending. Additionally, as calculated by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, expectations for "average annual inflation" in the U.S. over the next decade sank from 1.7 % in January 2020 to 1.2 % in April. As inflationary rates are dropping, deflationary rates are going up, which supports the Economist's argument that deflationary pressure will remain high.

Overall, The Economist uses contrast between the inflationary and deflationary impacts brought by COVID-19, appeal to authority by referencing the new economic paper published by renowned writers from several prestigious universities, and scientific data heavily to inform the public about the possibility of the return of inflation after COVID-19 is dealt with. The Economists' points are convincing to me, and their points make me think about the post-COVID-19 world's economy from a completely new perspective.

- 本文标签: 原创

- 本文链接: http://www.jack-utopia.cn//article/482

- 版权声明: 本文由Jack原创发布,转载请遵循《署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)》许可协议授权